Talking anime | Phoenix: Eden17

The world might be bad but anime? Anime good.

The earth is dying and we are killing it and every single person knows it. Some hem and haw otherwise, say it’s all overstated, all nonsense—why just the other day was perfectly cold, how could that mean the planet is warming?—but they know the truth. They lie to maintain money and power, to keep themselves in stasis while the world rots around them. They lie because others have told them and conditioned them to lie with promises of security and comfort, a cozy ideological embrace that “it’s all okay,” that what you believed and felt as a child wasn’t wrong.

Meanwhile, while the planet simmers, war and genocide and murder propagate like cancer. Every single day thousands are killed. Burkina Faso and Somalia, Syria and Ukraine, Yemen and Afghanistan; countries on countries are, as we speak, trapped in war and terrorism and unspeakable tragedy. But it isn’t just in countries so many “western” nations seem desperate to pretend don’t exist. Step home to America and see the destruction everywhere you look. Kill a woman before you let her have an abortion; kill a child before you let them be the gender they are; kill a black man for no reason at all.

Everywhere, every country, every second. The world is dying. We are killing it as fast as we kill ourselves.

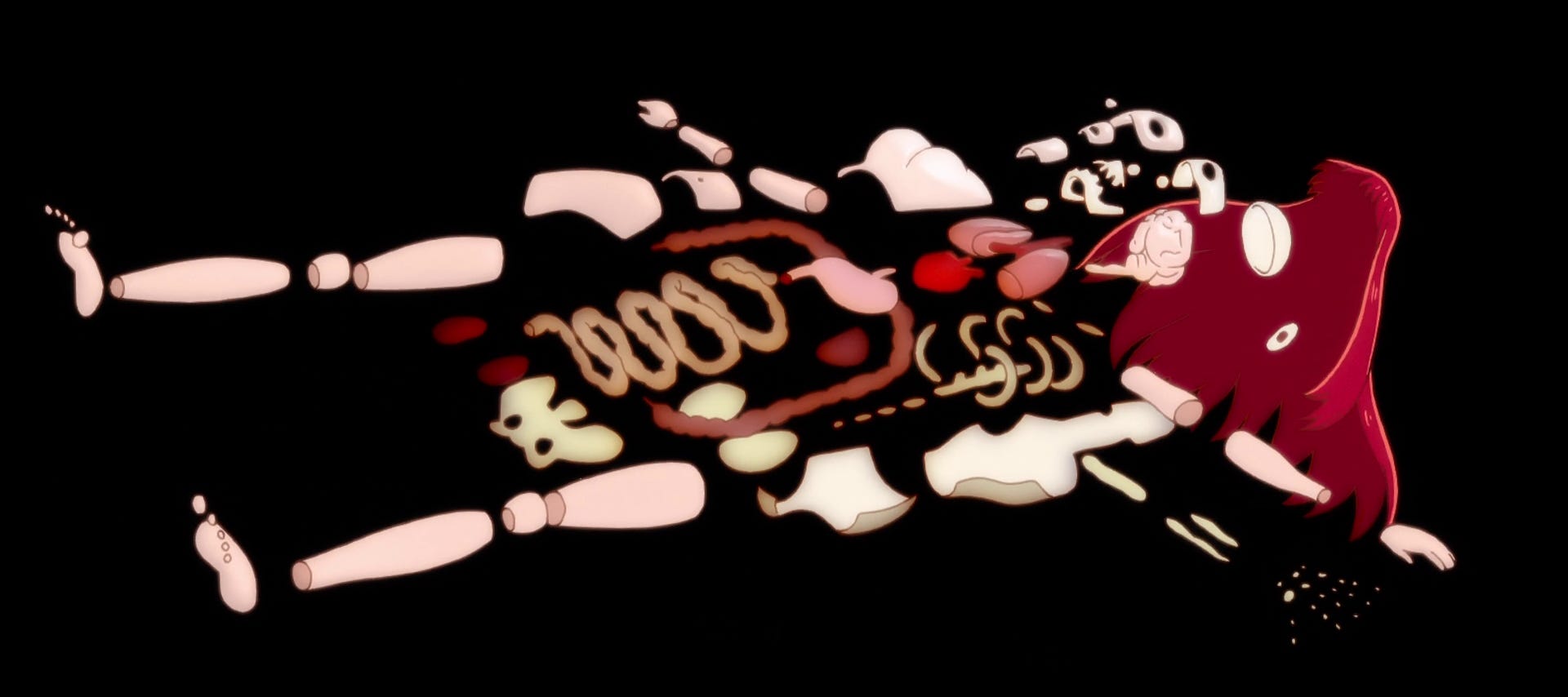

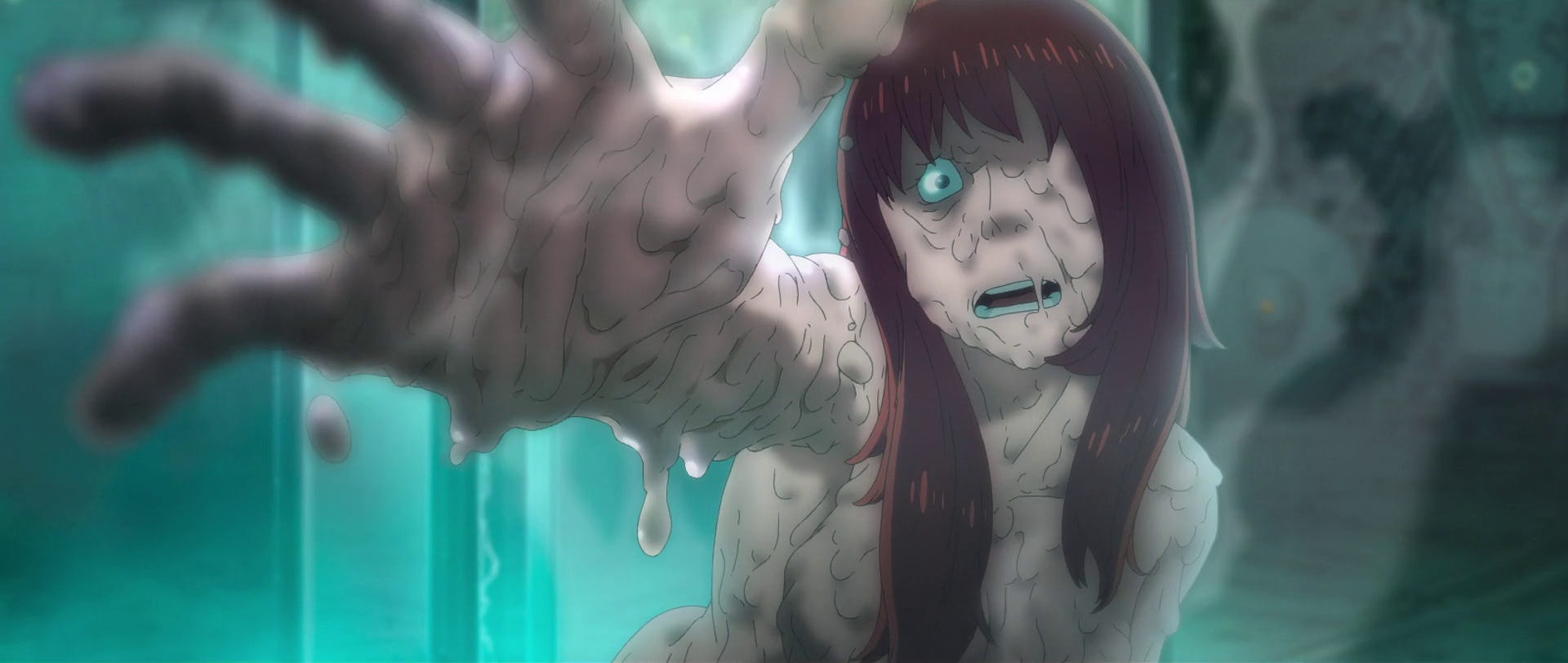

Phoenix: Eden17, the new anime adaptation of the “Nostalgia” story arc in Osamu Tezuka’s seminal manga Phoenix, is as fantastical as they come. There are aliens and spaceships and warp speed space travel, cryogenic sleep pods, robots, and impossibly massive superstructures. It is a generation leaping epic through more than a thousand years, full of cloning and lasers and planetary terraforming as it depicts the evolving life of a single, complex family. It hardly feels like sci-fi at all.

Following a woman who begins a new life on a desolate desert planet full of the ruins and crumbling ships of those who tried before her, the story quickly evolves in ways you couldn’t imagine. Just by the end of the first 30-minute episode, the woman gives birth and her son propagates with an alien that looks exactly like his mother and starts a thriving civilization—one which the woman arrives in after waking up from an accidental 1200-year sleep. Everything is moving and changing and new faster than you can blink—her husband dies, their attempts to grow life in the rocky earth fail, she becomes a queen—but a millennium passes and she hasn’t moved on a day. She is powerful, she is important, and all she can think about is Earth, the planet she grew up on. Isn’t that how it works? Time moves so fast; we live in the same few moments forever.

This is sci-fi in the way that another perennial favorite of mine, Toward the Terra, is sci-fi. Both are shockingly expansive and elegant works that spread across time and space, years passing in beautiful elliptical vignettes. Both are stories that transform the cosmic breadth of science fiction into a vehicle of pure emotional expression, where heady concepts like space-time dilation and wormholes are transformed into grand psychedelic floods of feeling made manifest. Both are also deeply honest.

The woman knows that her memories of Earth—the green grass and blue skies and gentle winds, the peace and the quiet—are a lie, an ideal crafted out of nostalgia, ignorance, and invention. But she can’t help it. It consumes her everyday. So, throwing away her new life, she returns to her old one.

There are few books that mean as much to me as Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet. Written by the master of a hundred heteronyms (like pen-names but each with a fully fleshed out personality), it is a work forever unfinished, forever unordered, and forever unknowable. Through short journal entries the book drifts through a thousand topics—hope, despair, work, death, art, time—from the stance of the narrator, a sad and isolated man. In one section, he suggests that daydreams are better left as just that: dreams. The true pleasure of a dream is in its infinite potential, in what one creates in their imagination, in the ability to return to the feeling of a dream over and over throughout one’s life. They were never meant to be fulfilled, he says, and if they are, no true satisfaction can come from them. And yet all of us, even the narrator himself, can’t help but reach for them, try with all our might to grasp on to those fleeting flights of fancy and make them true.

When the woman finally makes it back to Earth after a thrilling journey that finds her flung across planets and literally returned to her younger body, she realizes the truth of it, what Pessoa warned us about: she should have let her dreams stay dreams. Earth is not the Earth of her mind. The real Earth is one made entirely of metal and smog and trash and factories, one where there is no ground or sea anymore but wires and tubes, where the only humans left are the rich and the powerful and even they are more machine than man anymore, body parts replaced one by one in a Ship of Theseus play at immortality. It’s an Earth fully and irrevocably taken over by business.

Watching her confront this reality she always knew on some level was true feels strange. It feels like looking out the window.

In our post-capitalist world where less than a percent of a percent own all the wealth, independent work is increasingly difficult in the face of monolithic conglomerations buying out everything they can see without a single plan, gutting businesses for parts like they are old cars and laying off thousands while forcing a thousand more into impossible situations to satisfy abstract goals—the money of which is all funneled directly into that 000.1%’s pocket. It’s a world where everything has become profit, where we have been conditioned to “rise and grind,” to turn ourselves and our lives into objects of monetization, existence turned into avatars funneling money into those who continue to allow the planet to burn and crumble. Even this very anime is exclusive to Disney+, streaming platform for the world’s ultimate media conglomerate overlord. Nobody is free. It all feels so hopeless. It all feels so futile.

And yet, memories remain. We continue to dream. During the woman’s journey, for the first time in over a thousand years, time moves for her. She meets new people, experiences new things, is allowed to grow and change, and with that change, so too do her dreams evolve. The planet she landed on all those years ago was called Eden. She realizes she’s been chasing the wrong garden this entire time; a garden that doesn’t exist.

When they return to that planet named Eden, greed has turned it again into a wasteland much like Earth; ruins once more dotting an endless, waterless desert of wind and sand after centuries of war and fighting. Everyone she knew is dead. Everything she had built has been reduced to nothing.

Sitting in an expanse of dirt, she holds up a seed given to her by a friend from her past on Earth. She remembers what was before and what was after. She remembers how the story, her story and all stories, began. The phoenix, undying, watches with human eyes.

Maybe Pessoa was right, maybe he was wrong. Either way, we can’t help but try.

Birth and death; creation and destruction.

It’s all a cycle.

That’s all it ever has been.

Music of the Week: Taishi - Phant Solo II

Cinematic doujin breakcore dripping in mysticism and magic. Phant Solo II’s fantasy anime cover hides an entire film that never existed, a story full of grand melancholy and human transcendence through technological augmentation, both through passages of pastoral ambience and ear-bursting glitched freakouts. Sort of like Keiichi Okabe’s Nier soundtracks but harder.

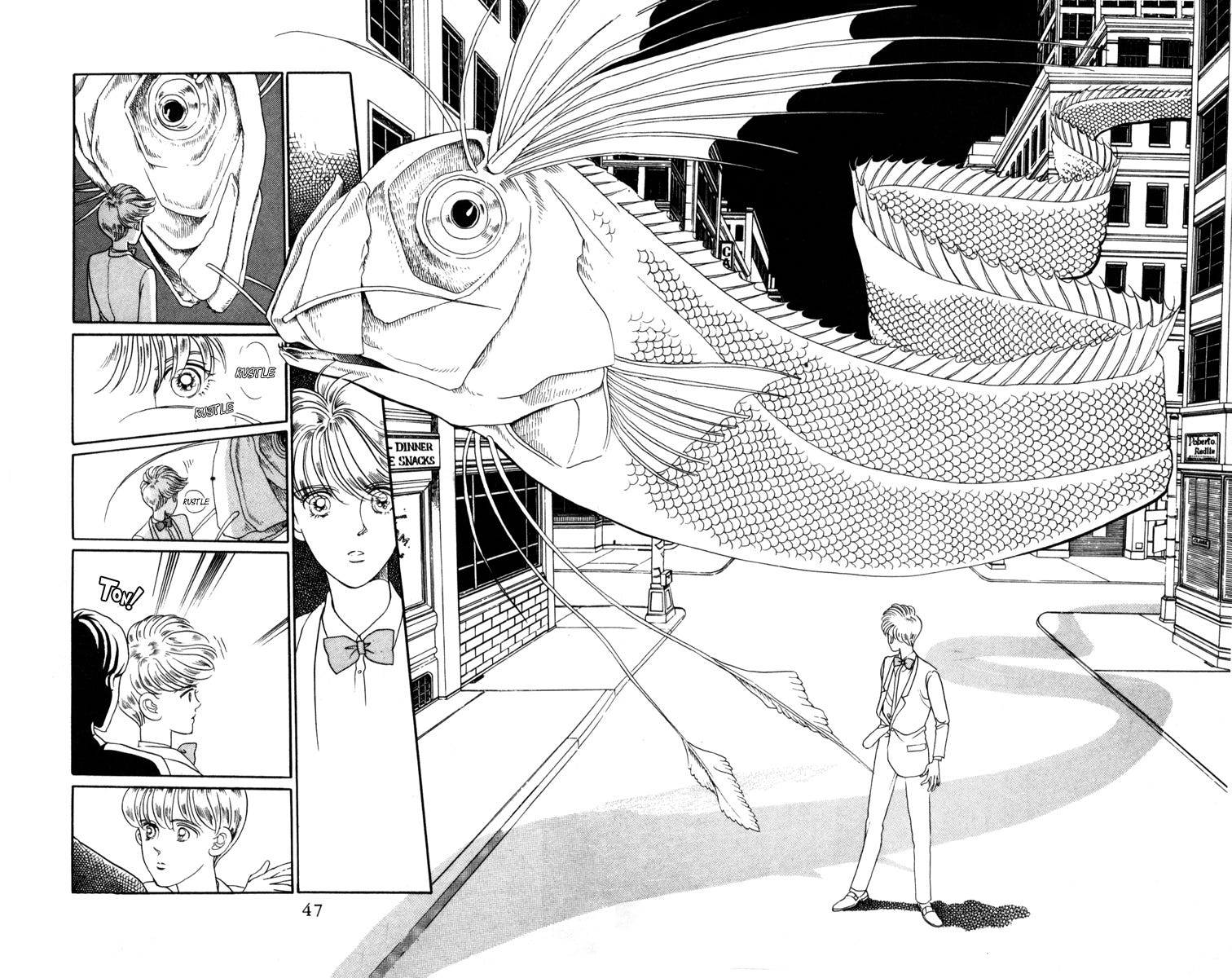

Book of the Week: Moon Child by Reiko Shimizu

A wild, complex, hallucinatory sci-fi melodrama overflowing with gender, the fate of the world literally wrapped up in a child’s decision to grow up into a man or a woman. Like a lot of author Reiko Shimizu’s work, it is purposefully messy, reveling in uncomfortable relationships and even more uncomfortable actions. And like a lot of art, it wouldn’t be half as good—or honest—if it didn’t. That Shimizu is one of manga’s best artists, with impossibly clean lines and a real love for negative space, doesn’t hurt things, either!

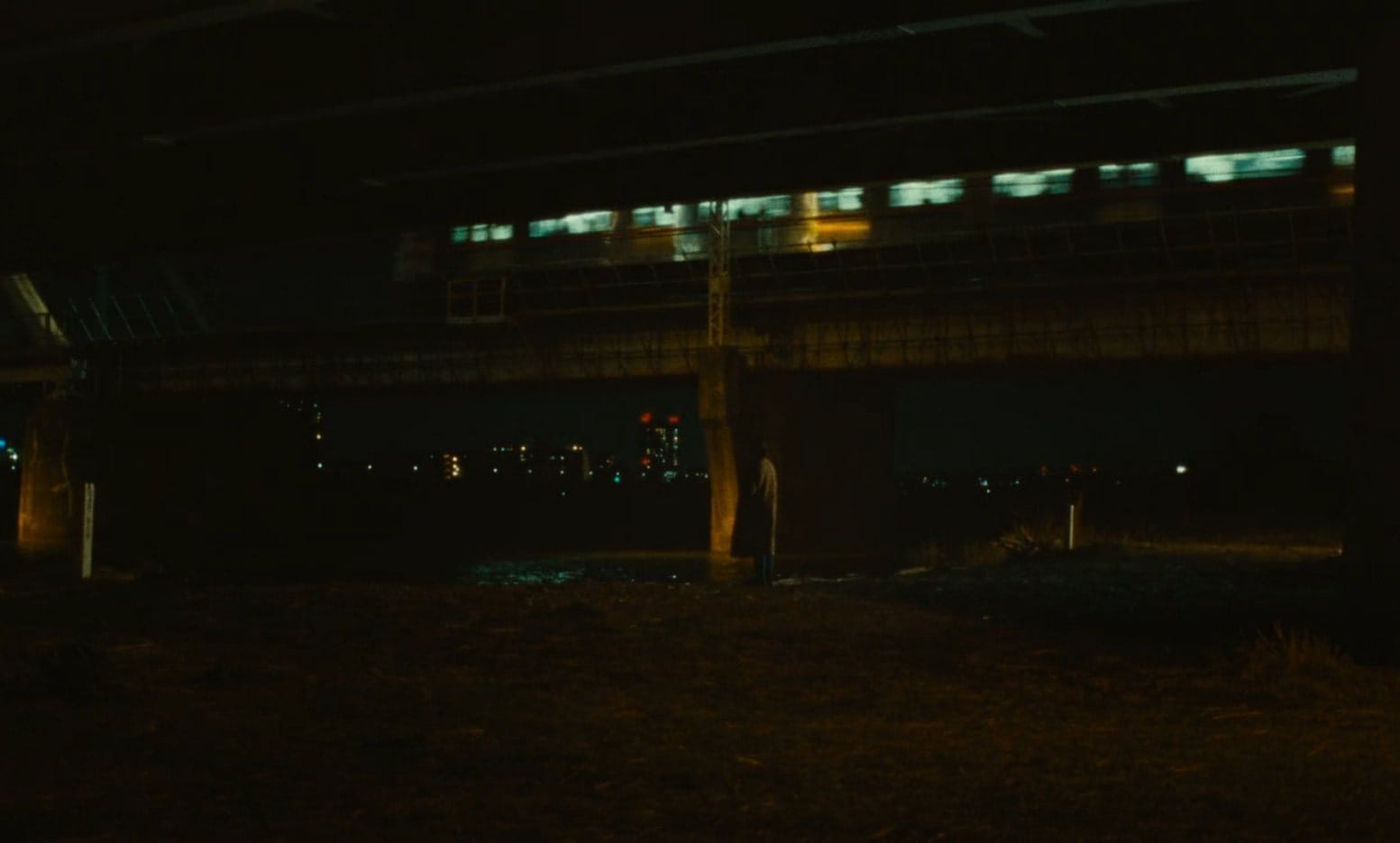

Movie of the Week: Small, Slow But Steady

Small, Slow But Steady takes the shape of the sports drama and turns it into pure ASMR intimacy; the story of a deaf woman boxer made near silent as it brushes against slow cinema, every moment filled to the brim with the sounds you only ever hear when the world is quiet: footsteps and fluorescent lights, a pencil writing, a hand brushing against some cloth. It also serves as a vehicle for Yukino Kishii, unquestionably one of the most talented young actors in Japan right now, who projects such realism and complexity without hardly saying a word. No title describes its contents better.

Thanks for visiting! If you liked what you read, share it around! It’d make my day :)

oh, and here’s a great piece about Mamoru Oshii’s singular and oft-forgotten Gozenso-sama Banbanzai!