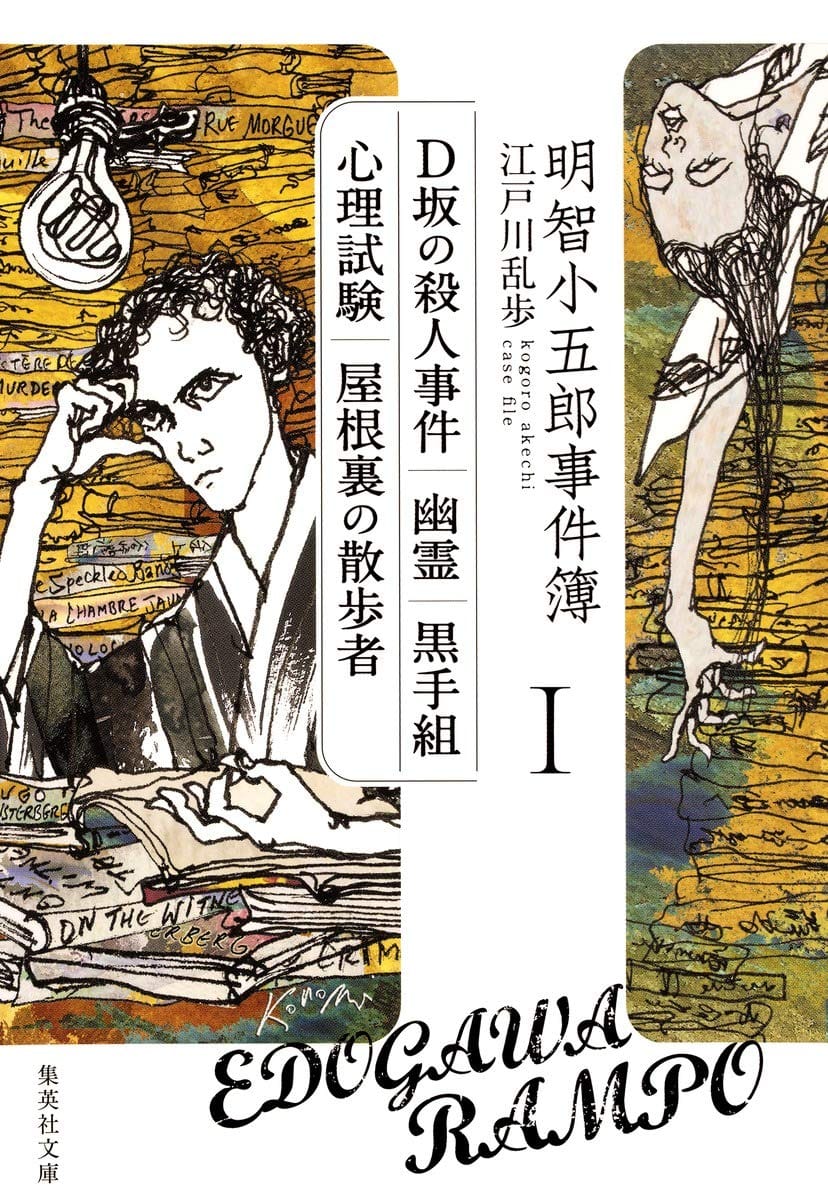

Talking books | The Case Files of Akechi Kogoro

Japan's greatest detective is making a voyeur of us all.

“The truth is, I search these kinds of things out. From the smallest recesses of society, I hunt the strange and the mysterious so that I may unravel their secrets. I suppose you could call it my vice.” - Akechi Kogoro

Akechi Kogoro is Columbo for Pervert Freaks. The pieces are all there: an affable man naturally gifted in social engineering who is a mystery in himself, personal life drawn in broad, unreliable brushstrokes except for the existence of a wife (and it is hard to imagine them being married); a protagonist perpetually late to his own story. The main difference, really, is that beneath it all Columbo is a good guy. But Akechi? Akechi is something else.

The Case Files of Kogoro Akechi 1, collecting the first five short stories of Japan’s most important detective, Akechi Kogoro, begins as iconic as you can with “The Murder on D Slope” (a goated title if there ever was one), and it doesn’t take much to see why the story found so much success. A reflective, meta-leaning mystery with a protagonist who watches other’s lives from behind the safety of café windows, idly daydreaming of being a Holmesian detective with a deep love of genre fiction as their education, “The Murder on D Slope” plays out almost like an anti-honkaku, a grand reveal of criminal genius gleefully deflated by Akechi. The protagonist thinks and plans and schemes like a reader, and when he solves the crime—presenting the complex web of cunning and coincidence one expects from the game that is mystery fiction—Akechi simply laughs and tells him no.

Here the “How” of the crime is as simple as they come, the seeming impossible nature of the case coming down entirely to the unreliability of humans. We are simple and foolish and blind, he implies. Murder is not like the stories. It is not a puzzle. It is messy and banal. It’s nonsense.

The stories continue in a similar vein, burrowing deeper into this psychologically-minded approach to focus almost entirely on the criminal themselves, the titular detective often only arriving in the last few paragraphs, becoming an almost inhuman presence, a sort of manifestation of guilt and ruin. As each protagonist finds themselves at their wits end, their actions gradually destroying their mental state, Akechi appears, and when he laughs and the world collapses.

All of this culminates with the final story of the collection “The Walker in the Attic”: an uncomfortable, mean, confrontational masterpiece.

Like the others, “The Walker in the Attic” follows the criminal. Like the others, he’s interested in crime. Influenced by talks had with Akechi Kogoro about the cases he has solved, the killer delights in playing make-believe, in imagining himself committing crimes. The real world is so boring, he thinks, the real world is so expected. But in the fantastical tales of Akechi, he sees the thrills and liberation unattainable in life.

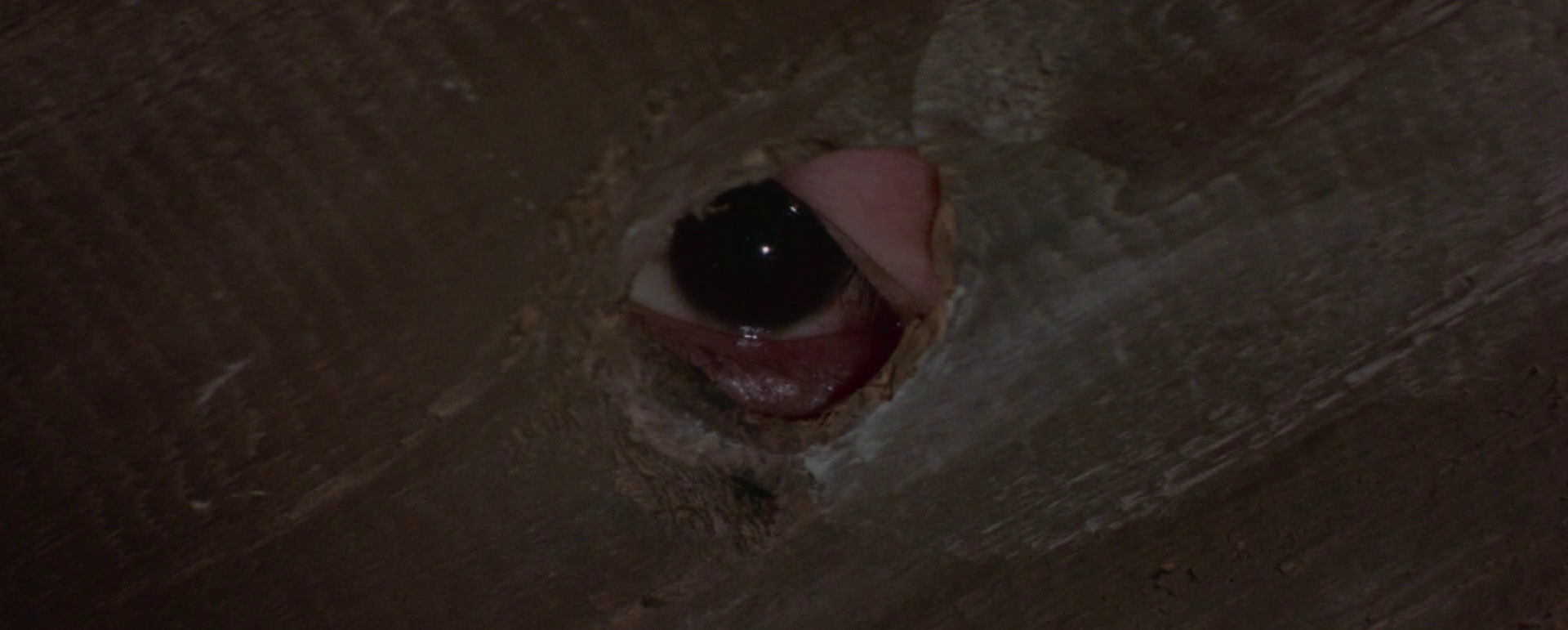

While at an inn, he finds a way into the attic which stretches out above the rooms, full of gaps and holes to peer into. Up there, he acts as a voyeur god, spying down on others in their most vulnerable from a detached, abstracted angle. Day after day he walks and watches their shame, their fear, their violent desires. He is like a horrible reflection of the protagonist in “The Murder on D Slope”, idly watching the street as if waiting for something to happen.

And then something does. He finds the room of a man he hates and he has a horrible idea.

It’s not exactly hard to read “The Walker in the Attic” as a critique of the reader.

And why shouldn’t it? One hundred years later and we haven’t changed an inch. True crime has given way to a bizarre cult-like industry where we hunger for crime and delight in playing amateur detective. Communities are destroyed, lives ruined, trauma exhumed as all of us don deerstalker caps and turn tragedy into a puzzle box. We delight in witnessing depravity, in imagining crime without ourselves being culpable: shock sites and snuff gore a click away, serial killer fandoms condemning and desiring in equal measure. We are so hungry that we reach out and consume the ordinary, the internet analyzing and extrapolating until everyone is the main character of an Akechi story and everyone is Akechi himself. Bean Dad, West Elm Caleb, that one kid who didn’t show the proper level of excitement at seeing his girlfriend—all main characters to catch, to stop, to dox and harass. The internet has become an attic; we are all its walkers and its victims.

When Akechi finally shows up to confront this killer born from him, he doesn’t arrest him. That’s not why he’s there. He doesn’t care about stopping murder or bringing justice to those wronged—not really. No, all Akechi cares about are answers. All he cares about is a story that satisfies him. And that’s because unlike Columbo, Akechi is not a good guy.

He’s us.

Music of the week: Funeral Party - Dream of Embryo

Part of the greatest genre: music with Suehiro Maruo cover art. The group only ever put out these two tracks (under this name at least — they also released some solid gold as Pale Cocoon), but what tracks they are; the most gothic, despairing, theatrical coldwave you'll hear, like the sounds of a decayed city slowly melting into a uniform ocean of black tar. Real Shin Megami Tenseicore.

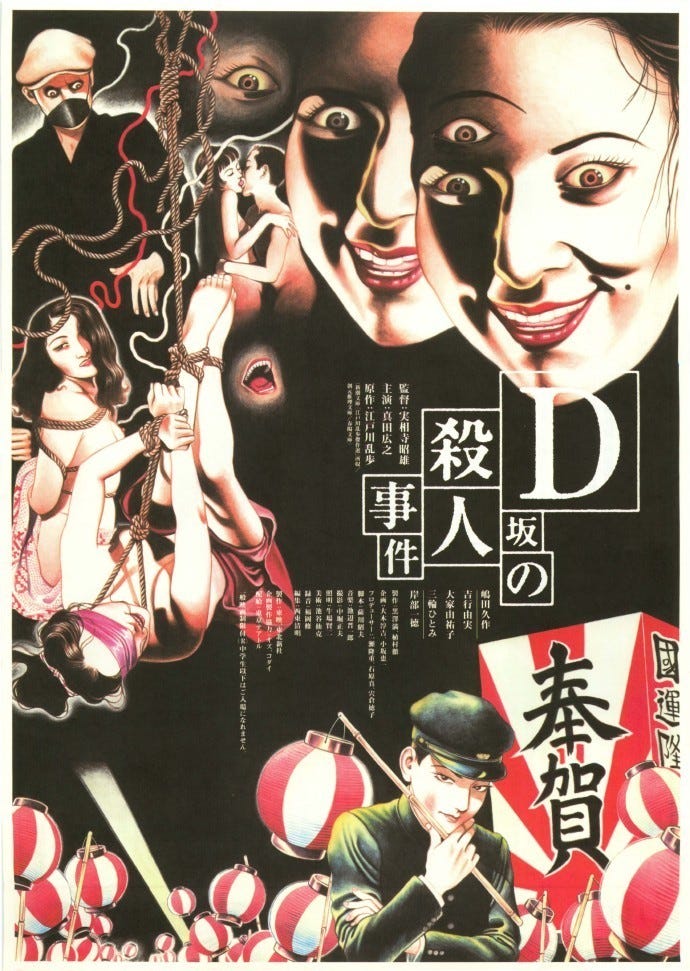

Movie of the Week: Labyrinth Romanesque

The director of Female Prisoner #701 makes a political whodunnit set in an upscale brothel during WW2. Starts with a literal wrecking ball to the screen and ends in the metaphorical ruins of a rotting country. In between that? An all-time dance sequence, voyeuristic Raimi-esque trench runs through a maze of vents, and one of the most mind-melting one shots in movie history. As angry as it is formally exhilarating (aka very).

oh, and here’s a very good essay wrestling with military prop in media