Talking games | D2

Welcome to the 21st century.

some spoilers for the 1999 Dreamcast game, D2

D2 ends with numbers. For roughly five minutes following its final scene, white text on black fades in and out without a single sound as the game lists the stats of our world in 1999. Roughly 3,000,000 people had been infected with HIV; AIDS had killed more than 2,500,000; there were 830,000,000 people starving and 1,000,000,000 who were illiterate and 2,000,000,000 without electricity; 19,000 children every single day were dying from malnutrition; 772,204 square miles of rainforest had been destroyed in 15 years and we’d raised the temperature by a degree in about 50; 11% of all mammals and all birds were on the verge of extinction, with an annual species extinction rate of about 1000. Over and over, D2 shows what was once the truth. It all seems so quaint today.

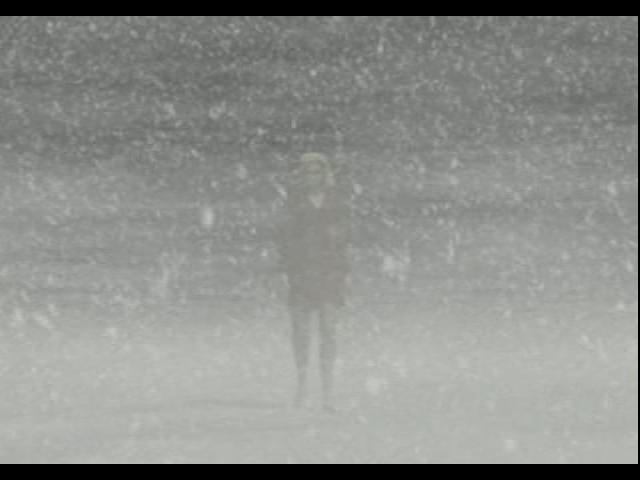

Released December 23, 1999–only a week away from Y2K and an unknown century—D2 plays out like an elegy to those numbers. It is survival horror as poetry, a game of tragedy bringing tragedy until there’s nothing left to give, a beautifully abstract, impressionist lament to the things humanity has lost and continues to lose just by being us in all our blindness. Taking the skeleton concept of The Thing and splaying it out across the entire earth until its sci-fi concepts have been stretched to symbols of pure emotion, it is very possibly the ultimate work from gaming’s great eccentric auteur, Kenji Eno.

It’s also a game people don’t like much. It’s not hard to see why. From its opening cutscene, D2 aggressively establishes itself as existing outside mainstream gaming’s definition of “good taste”, an assertion it continues to constantly make throughout its eight or so hours. Beginning with its mostly mute protagonist Laura flirting with an FBI agent on a plane that’s also being hijacked by extremists, is housing a cloaked warlock chanting a curse, and is manifesting visions of a meteor crashing into the plane in Laura’s compact mirror—visions that quickly come true and see the plane falling into the snowy Canadian wilderness filled with mutating psycho-sexual body horror people—the story here is at once incredibly loud and quiet as can be, increasingly large and surreal events playing out in shocking moments between elliptical treks through snow and gore.

Things don’t get more normal once you start playing, either. Deep in the age of Resident Evil having already codified what survival horror means, D2 all but ignores its contemporaries for its own vision of an exploding genre. There are tank controls yes, but also first person exploration à la Myst and random battles complete with EXP and fights that are essentially on-rails shooter segments. Puzzles are light, the map is vast and open instead of a compressed maze, and wildlife wanders waiting for you to hunt them without the slightest mechanical sense of urgency. It’s a lot, a frantic grab-bag of ideas acting in sharp contrast to its icy environment and long stretches of silence. At the same time, what initially gives whiplash gradually reveals a meditative rhythm, a semi-regular switching of perspectives and controls highlighting the fractured state of Laura and the strange world around her while also establishing a methodical pace that beautifully reflections the game’s tonal and narrative concerns.

With a script by Yuji Sakamoto (a screenwriter best known to the English world for Hirokazu Kore-eda’s recent Monster, but who made a name defining Japanese television for decades with colossal hits like Tokyo Love Story and who had worked with Eno previously), D2 is filled with poetry. Everyone speaks in soliloquies and extended metaphors, but it goes beyond only words. This is a game where large swaths of cutscenes are of disembodied voices echoing over images of snow, where events turn increasingly symbolic through its run, where brief visual asides are filled with potent meaning and gameplay takes surprising turns decided purely by emotional expression (I won’t spoil it, but the final boss is astounding). You can see poetry everywhere you look here, but perhaps nowhere more clearly than with Kimberly, its secondary protagonist. A former poet herself and recovering drug addict, early on she lets you hear one of her poems recorded onto a cassette tape by a singer she’d never met. It is one of the last surviving things from before the crash.

“Poetry, to me,” she says as the song, about counting all the beautiful roses in the world, plays, “is like creating my own microcosm. A sanctuary of comfort....I recently went through some of my poems and I realized something. Every one of my hundreds—no, thousands—of poems…they were so sad.”

The cassette breaks.

I’ve made plenty of microcosms, of little universes, too. Who hasn’t? I’m doing it now, writing essays on art in a desperate, contradictory attempt to escape the world by looking in and finding some sort of understanding myself. Creating can feel like the whole entire world has slipped away, that nothing outside of the place you’ve created matters an inch. That’s just part of art, I think, and there’s more art now than there have has been before. It’s both a tool of radical empathy and deeply isolated introspection that continues to grow exponentially, the number of stories being told expanding on a level nobody could ever hope to comprehend while the stories of our past continue to live right along side them.

Similarly, the universe Laura has made—Eno’s universe? The player’s universe?—seems impossibly large, but she doesn’t know it, because when Laura wakes up after the crash, she wakes up empty. She’s missing several days, a great blank spot filling up her mind like the snow that surrounds her. She spends a lot of time simply trying to remember people’s names. Who are they? Who is she? Who is anyone? Remembering won’t save her, it won’t get her out of this wasteland, but it feels important all the same, like just knowing who these people are might free her in some way, let her escape the microcosm that has trapped her.

But then, it isn’t just Laura that has something missing. It’s the whole world. No video game location is truly realistic—they squash and stretch geography and geometry, simplifying structures and places into symbols (a town is just five buildings and three NPCs for example)—but even then D2 pushes the abstraction of place. The game ostensibly takes place in as middle of nowhere as you can get—a place where no one exists and every day is a fight for survival—but there are disparate buildings strewn around the mountains with little consideration for practical logic. Here’s a fully furnished home, there’s a log cabin, beyond a bridge is a pharmacy and an impossibly large science lab that towers so high you might mistake it for a mountain. And all of these buildings are strange on the inside too, extending farther than they ever should with hidden caverns and rooms deep underground or escalators going up to heaven. It feels, in some way, like the interior of our emptied, scattered protagonist has been made physical, actualized into the very ground she walks on. It feels, in some way, like the story of D2 with its elliptical melancholy, like its scattered and meditative gameplay loop and tone. Every bit of D2, from toe to tip, is Laura’s own microcosm, which means it is just as much a microcosm of all of us who play and watch and walk through it. In that way, maybe the impossible blizzard ruins of D2 aren’t unrealistic at all. Maybe they depict our real world as honestly as anything ever has.

Laura only ever speaks a few times in the game, and never in full sentences. She just gasps, groans, and whispers her name and the names of others that she remembers, repeating them constantly like mantras. Every name she learns, every name she speaks, always and inevitably ends up dying. They leave her, one by one, finding poetry and peace as this alien mutation takes them, until she’s the only one left. Just her, death, and the earth she walks on. And after hours of repeated tragedy, loss on loss, Laura finally opens her mouth and screams. It’s loud, it’s long, and it’s ugly, a disconcerting break from the mostly silent character archetype and distinctly lacking in the theater usually attached to similar scenes. She cries, she mourns, she continues on.

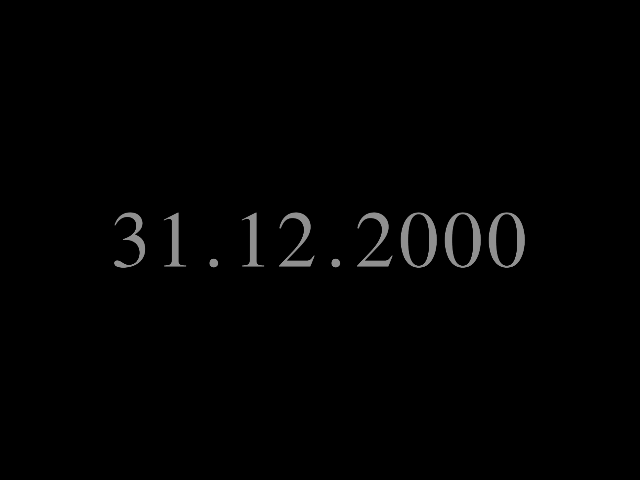

In the end, Laura remembers those names that mattered most to her, even if they all (inevitably) leave her. And with those names comes power and possibility. By remembering, by knowing these faces and these names, de-abstracting both others and herself, there is hope. The snowy dream world of isolation and coldness melts away for bustling New York. And after all is said and done, after the numbers fill the screen and the credits finally roll, set to that beautiful song based on Kimberley’s poetry performed by Arto Lindsay, D2 finally ends with one more number.

It’s the time. A real-time clock fills the screen. If the game was played when it came out, at the edge of the millennium, it’d display a message at midnight as the numbers shift to 2000.

“Welcome to the 21st century!”

Now, twenty-five years later, it simply counts up, showing you exactly how long it’s been since all those numbers and all those statistics mattered.

September 13, 2024.

7,059,612 people have died from COVID since it first developed 5 years ago; 27 have been killed in mass shootings in America in the past nine months; 6,178,741 have died from hunger this year; 86,517 died from natural disasters last year and 1,520 this year; 41,020 have been killed in Gaza since October and roughly 16,500 of them children; an estimated 700,000,000 people in the world are living under extreme poverty;a year into the Sudanese civil war and more than 14,000 have been killed and 8,000,000 displaced and almost 18,000,000 in danger of starving; ten years into the Yemeni civil war and more than 150,000 have been killed with the number more than doubling to well over 377,000 dead from indirect impacts; 429 civilians in Syria were killed in the first half of this year alone, with a war total now well over 507,000; at least 150,000,000 in the world are homeless; Myanmar has seen at least 50,000 people slaughtered, 221 killed in a drone attack only a month ago; as of 2016, there are 40,300,00 trapped in modern slavery; some 2,200,000,000—1 in 3 people in the world—lack regular access to safe drinking water; and 35,160 civilians have been murdered during the Russian invasion of Ukraine; exploitation, abuse, suffering, violence, death, death, death and numbers, numbers, numbers—numbers that are already outdated and numbers so high they don’t mean anything anymore and make me feel nothing looking at them even though I know full well that each and every one of those numbers is a person like me with just as many universes hiding inside of them and holding more poetry in a fingernail than any word or image or idea ever could but I don’t know any of their faces or the clothes they like to wear or the music they like to listen to or what they dream of or hope for or love and hate or believe or pray or even something as simple as their names. I don’t know a single goddamned one of their names.

It’s been twenty-five years since D2. The snow falls heavier than ever.

Welcome to the 21st century.

Music of the Week: Mofu’in by pppppfffffuuuuuiiiii

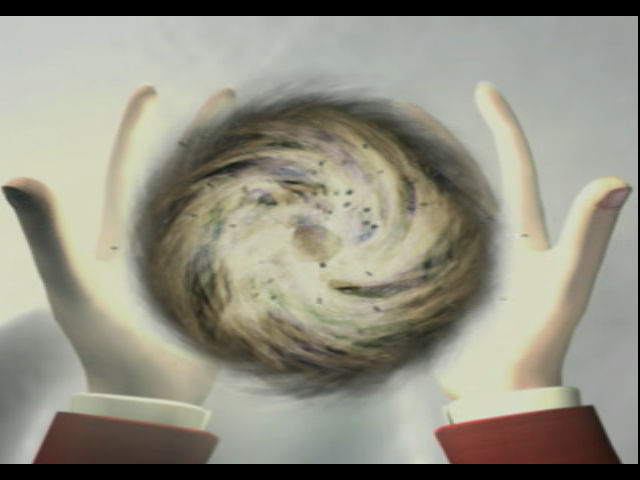

If we’re talking about depicting our times, then this new album from one of the most fun artist names to say is a perfect representative. Glitchy, drum n bass soundscapes swirl and explode like fireworks under jazzy melodies. Skittering, fractured, overwhelmingly full, Mofu’in captures the strange isolated connection defining the post-COVID era while also being just immensely fun. Less mind-blowing and more mind-expanding, like your brain has turned to silly putty and pppppfffffuuuuuiiiii is stretching and kneading it into shapes you never knew possible.

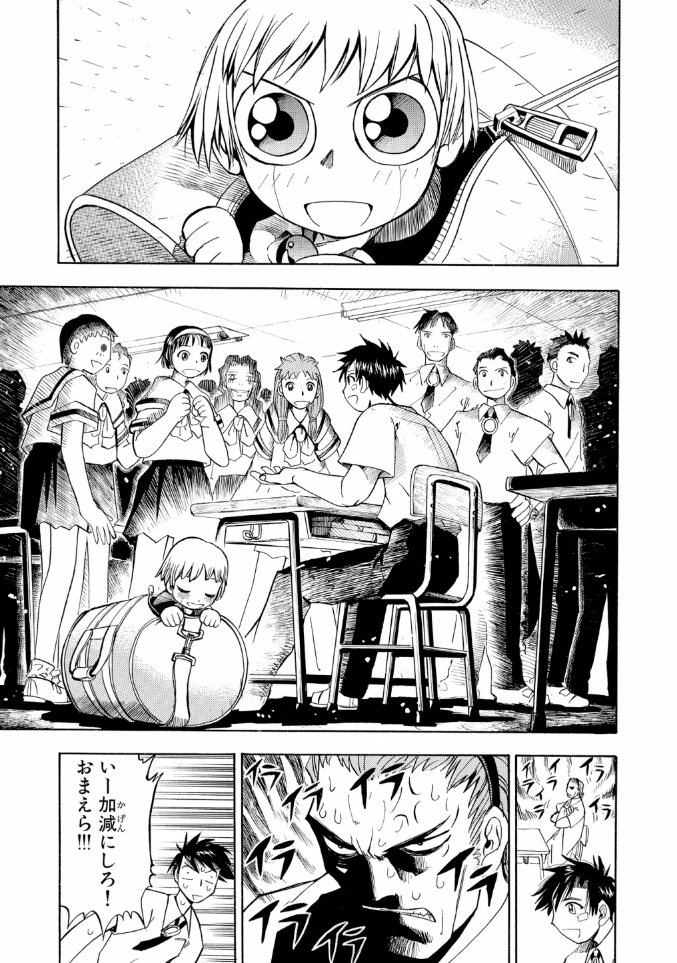

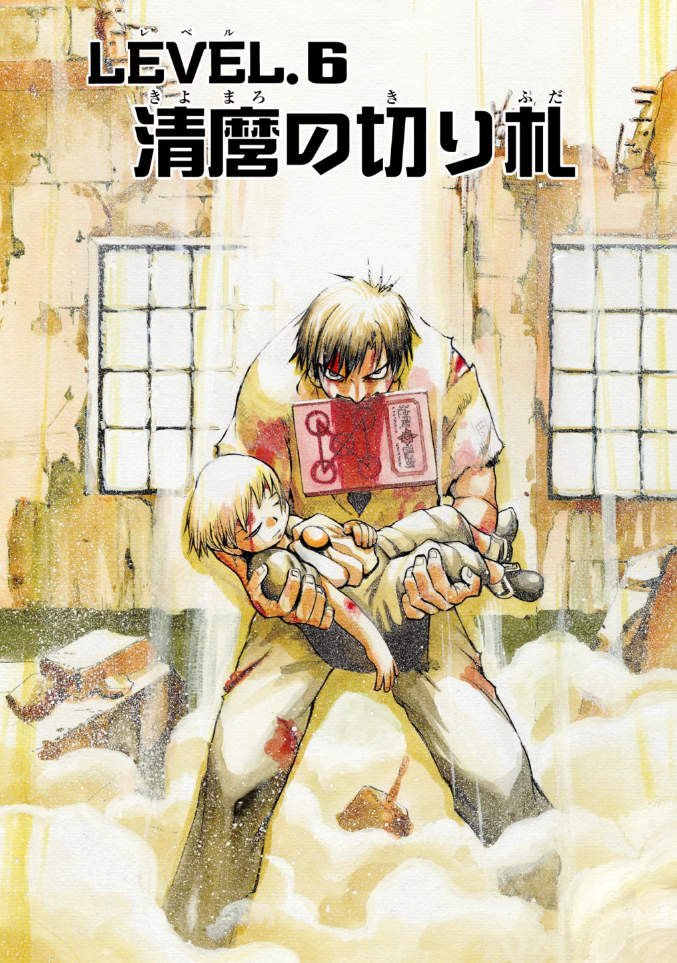

Book of the Week: Zatch Bell by Makoto Raiku

I don’t know man, Zatch Bell might be the greatest battle shounen of all time. I’ll fight to the death to make sure it’s at least in conversation. A descendant of the Kazuhiro Fujita (Karakuri Circus, Ushio and Tora) school of the genre, Zatch Bell revels in weekly adventures, crystal clear character work, heavy amounts of absurd comedy, and a heart-on-its-sleeve honesty about every single thing it feels that each chapter leaves me on the verge of tears because look at these people standing up for what they believe in and never giving up. The definition of joy; the kind of story that makes you want to be a better person.

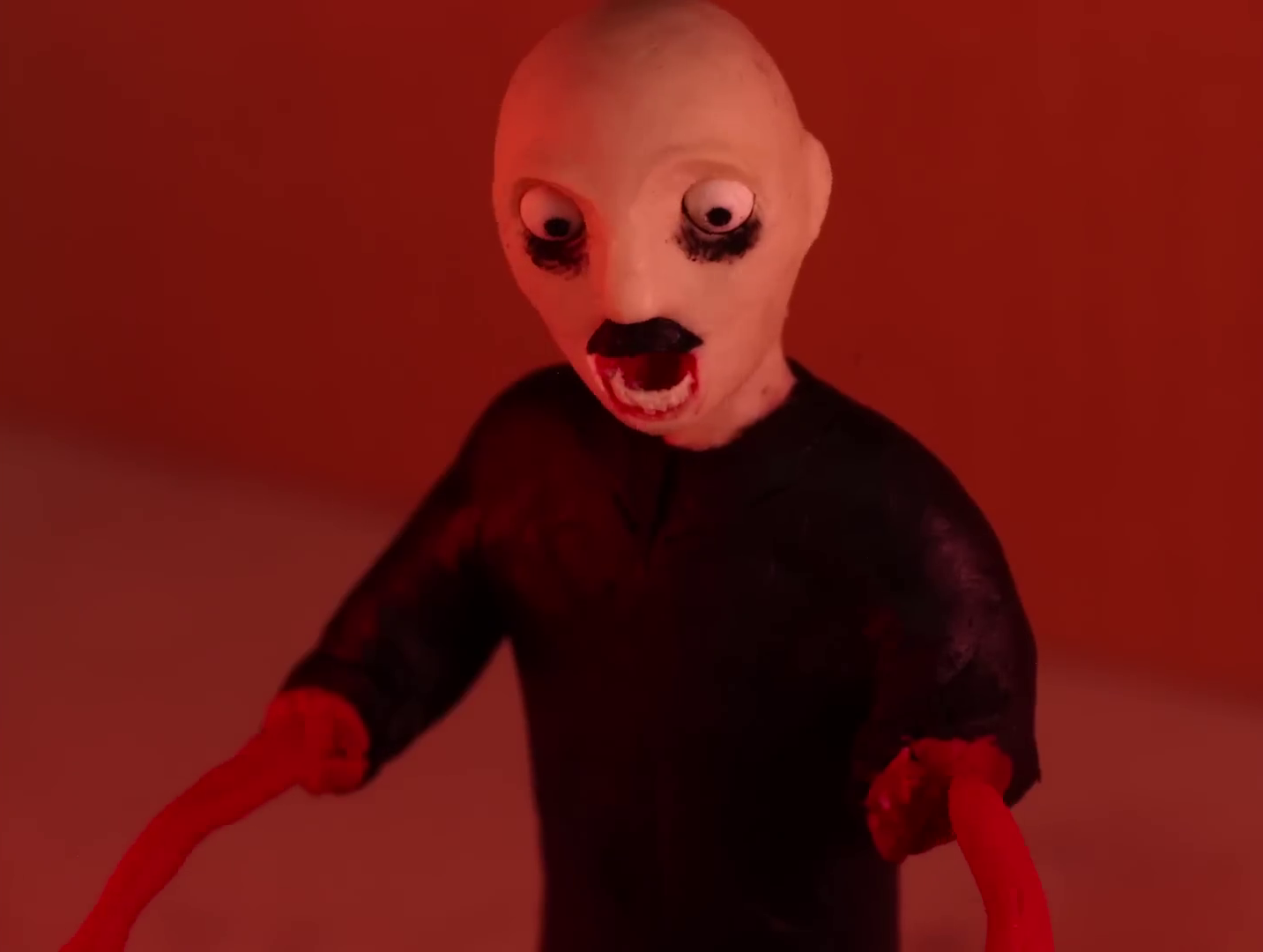

Movie of the Week: Midnight Vampire (dir. Takena Nageo, 2024)

Nageo has spent the last decade plus releasing wild claymation short films to YouTube that run the gauntlet from funny, hip, and profoundly upsetting. Really about the only thing you’re guaranteed is buckets of clay gore. And their latest, Midnight Vampire, is as perfect a distillation of their work as anything: quirky and full of iconic imagery, but with an upsettingly dark underside and surprisingly complex thematic considerations. Less than ten minutes and still the coolest film of the year.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!