Talking games - Kowai Shashin

The (not so) true story of a haunted gam.

Hey all, taking a week off because…I’m tired! Finishing things is hard and my brain is fried! So enjoy another one from the archive as we rapidly approach the spooky season: a big long look at a PS1 horror game and the urban legend surrounding it.

In 2002, at the height of a nonstop blitz leading up to their latest release, the president of Japanese game development company Media Entertainment called a meeting. It was already well into the evening, the sun having probably set long ago. Walking into the meeting room, everyone already knew what had happened. They could feel it in the air; the news they all expected, the news they dreaded most.

Lead developer, K-Kawa, had died, their body found in a train station bathroom only a few hours ago, hung from the neck to one of the stalls. Suicide. One developer, a woman who had been with the company for years, walked out on hearing the news and never came back, the final straw of months of escalation finally broken. It wasn’t just the death, tragic as it was, that bothered her. It was the location. She, and everyone else in the room, was all too aware of where the station he died was, and what it meant for the rest of them.

On July 25th of that year, Media Entertainment released Kowai Shashin: Shinreishashin Kitan for the PlayStation to little fanfare. The next year, the company would quietly die. But what they left behind is a legacy, a story, and a game that continues to haunt the history of Japanese game development like a ghost; one which reveals so much more than anybody could have ever imagined.

It is a story that starts like it ends: with a meeting. While brainstorming for their next project, an intended summer release, the creative staff at Media Entertainment (a small development studio focused on small budget games) found themselves enthused with a trend that was in vogue in Japan: spirit photography. It was perfect — just as scary stories have become synonymous with fall and Halloween in America, summer is the Japanese season for scares. Without question, this is due in part to Obon, a two-day August event where departed spirits are welcomed back to their homes; a time for family and remembrance. Just as the Christmas spirit gradually (or immediately depending on who you ask) seeps back into the cultural consciousness as the day draws nearer, so too do thoughts of the departed — spirits and ghosts and the past — as Obon approaches.

But there is another theory that supposes the summer tradition of scary stories is actually because of the heat. Finding origins in kabuki theatre, there’s an idea that the chill that runs down the spine when scared produces a refreshing coolness among an audience, a brief relief from the sweltering, humid nights. And indeed, much of kabuki theatre concerns itself with tales of the supernatural and the terrifying.

Regardless of the reason, K-Kawa took to the idea immediately and, in the excitement of the meeting, suggested pushing the concept even further. Why not, they proposed, use real spirit photography; genuine, unedited photos of purported hauntings which the player could genuinely exorcise for themselves?

It was an idea nobody could ignore. The marketing potential alone was irresistible, and so only days later, a few members of the staff, K-Kawa included, would set out to find these real, undoctored images of ghosts, completely unaware of what awful conclusion this path would lead them to.

Spirit photography has existed for almost as long as the medium of photography itself. As early as 1856 — less than 40 years after the invention of the camera — people have tried to replicate and capture a world beyond the visible. These early examples were largely byproducts of long exposure times or experiments with glass and mirrors, but as the form was so new, many could not discern these techniques from reality. People believed in them, and with belief comes those willing to exploit it.

An entire industry of exploiting the mourning was born, and another industry of those dedicated to disproving them. And though it was during this time of spirit photography becoming a business that the first known example made its way to Japan in 1874, it would be one hundred years before they truly took hold of the Japanese public consciousness during the birth of the Showa occult boom.

The 1970s were a time for Japan of immense change, anxiety, and stress. Coming directly off of the politically furious ‘60s, worries of a nuclear attack from the Cold War hung over the country like a smog, and collective scars of Hiroshima were still bleeding. Faced with continued rapid industrialization, fears of destruction by pollution exacerbated the constant struggle between modernity and tradition.

Most famously, these anxieties were represented by the 1973 release of two novels: Japan Sinks and Prophecies of Nostradamus. Both hugely important works in understanding contemporary Japanese pop culture (their influence strong even today, Japan Sinks having received an anime adaptation in 2020), they both revel in collective fears, depicting the collapse of Japan through both natural and unnatural causes — nuclear fallout, earthquakes, tsunami. The delineation between these modes of destruction is blurred here; the natural and the man-made both violent reactions to the way we live. It is as if the novels suggest it is all inevitable somehow. Nostradamus predicted it all, after all — the end cannot be avoided.

With the massive success of these novels, it is perhaps unsurprising that a year later, the TV series “Anata no Shiranai Sekai” began in the heat of summer, pioneering the world of nonfiction television dedicated to the occult. Taking advantage of the sparked interest in this field caused by Prophecies of Nostradamus and its supposed predictions of the future, Anata no Shiranai Sekai focused itself on spirits and ghosts, re-contextualizing them as manifestations and outlets for societal fears. The ills of the world are represented by the dead; the past haunts the present. If people can release their worries by creating ghosts, then maybe they will finally be able to relax, if only a little.

Reenacting supposed supernatural phenomenon experienced by viewers followed by interviews and discussion with a panel of psychics, exorcists, and spiritualists, one of the most common topics was spirit photography. It was perfect, after all: visual and exciting, and possible for viewers to capture themselves. Here, anybody could have a paranormal experience and a chance to make it on TV.

The show was a monstrous hit, birthing several copies as other networks tried to cash in on the success. By then, the ball had already begun to roll. Movies, books, lectures, and lessons on fortune-telling, ghosts, demons, astrology, psychic powers, exorcism. Before long, spirits had taken over Japan.

Despite their best efforts, the staff at Media Entertainment found finding actual photographs of spirits much more difficult than anticipated. Most they came across were clearly faked, cheap attempts at making quick money in an industry that had been around for a hundred years. But it was within that industry that they would finally find success. A company directly involved in the business of spirit photography — one which worked as a liaison between spiritualists and TV and radio programs like Anata no Shiranai Sekai. Charmed by their vision, a deal was struck, and Media Entertainment received a collection of 30 photographs from a single spiritualist, all guaranteed real and unexorcised.

And as they waited to receive their collection of photos, the other team was putting the finishing touches on the basic gameplay systems of their soon-to-be product.

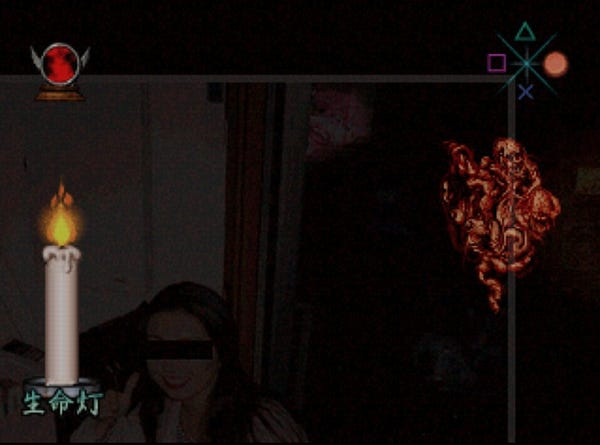

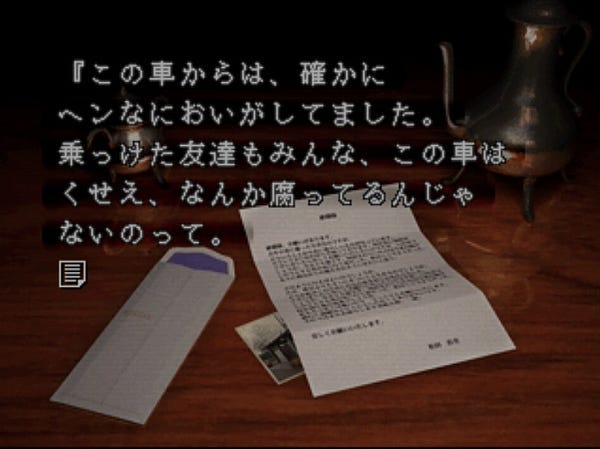

At the most basic level, Kowai Shashin resembles a game of I Spy. Using a cursor, the player races against a clock (visualized by a melting candle) to find and exorcise all the spirits hiding in each photograph. They might be the shadow of a face on someone’s knee, or a missing limb that should be there, or as obvious as a bleeding head in the middle of a trash pile. The twist to the formula is that to capture a spirit, you must enter searching mode, which more than doubles the speed your candle burns. And due to spirits being larger than the objects you’d typically find in a hidden object game, an element of blind guessing is present — even if you see the ghosts, you still have to hit the very specific connection point of their image to succeed.

It sounds like a recipe for frustration, but in practice creates an exciting tension. Precious time necessarily sacrificed for progress, the push and pull between slow, atmospheric searching and the mad dash of scrubbing an area with the cursor transforms a flat gameplay loop into something with pace and drama.

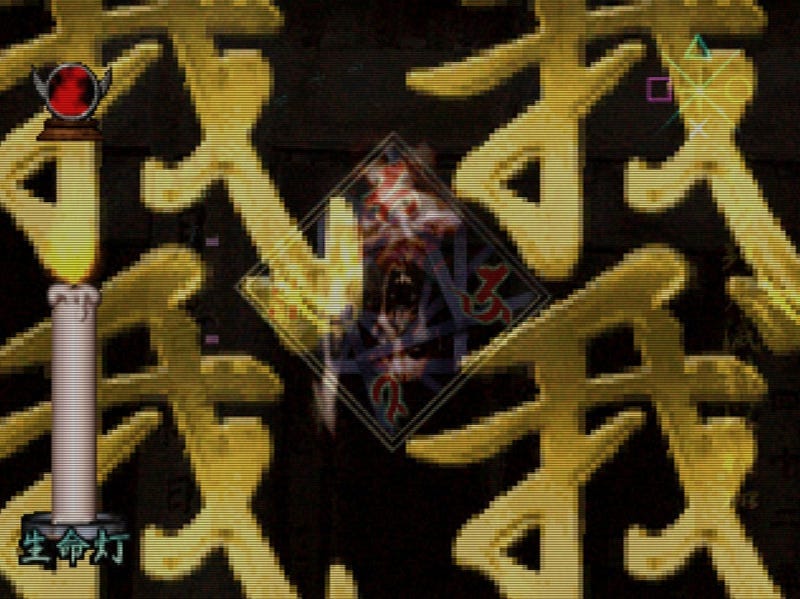

Once the spirit is found, the game enters its second phase: a QTE-based reflex test, static images of evil spirits flashing in and out from one of the four cardinal directions, which correspond to the controller’s face buttons. Miss enough times and the spirit will attack, taking some of your life (which is confusingly represented by the same candle as your time). Various spirits have various patterns and speeds to learn, ensuring that battles do not become too predictable.

It is a simple system, but also an effective and surprisingly meditative one. There is something to be said for the baked-in repetition here, allowing the player’s mind to relax as they acclimate to the ebb and flow of the game, atmosphere taking center stage.

The problem was, there was still no exorcism. At this stage of the game, the ghost is caught but still exists, and the development team had no idea how to proceed with creating real digital exorcism. So, not long after arriving at a deal with the company, they reached out to the original owner of the photos they were now using for ideas. Everyone was prepared for the worst — they knew their game was blasphemous and asking someone who has dedicated their life to spirits how to perform an exorcism for fun was surely not going to go over well — but surprisingly, the spiritualist agreed to help immediately. They had only two requests: that their name would appear in the credits, and that they would be paid.

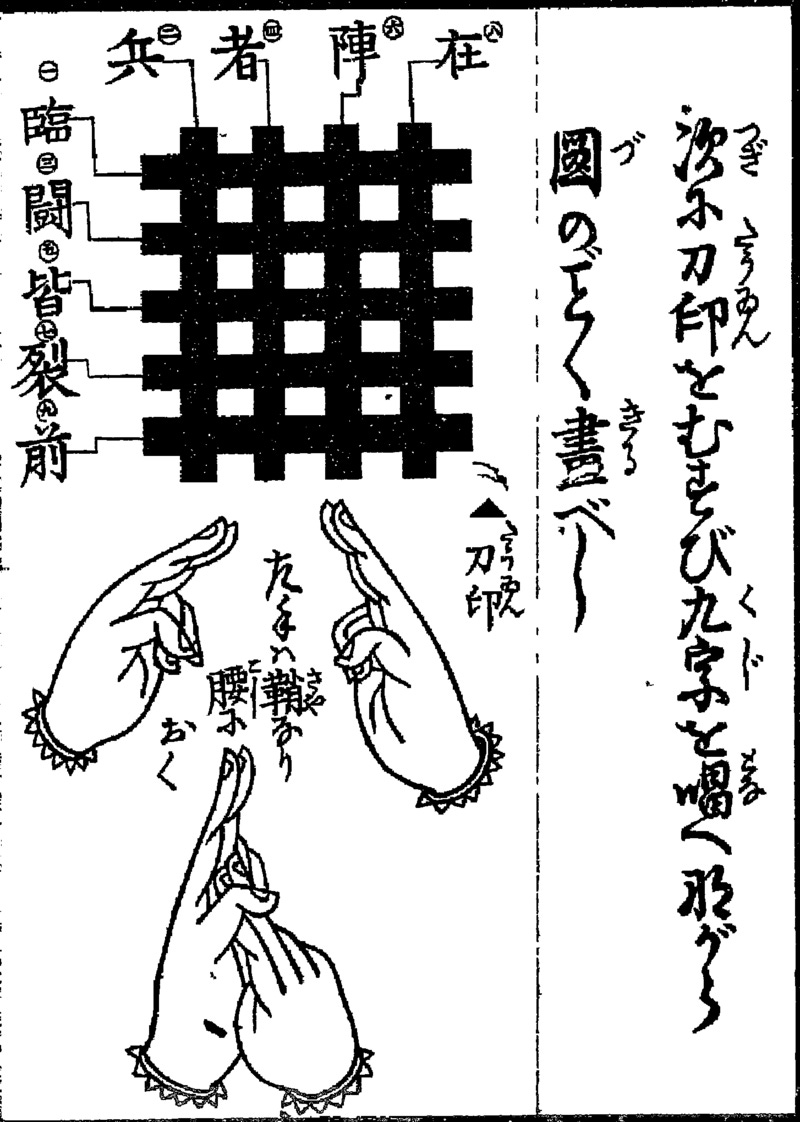

Working with the eager spiritualist, Media Entertainment eventually settled on a system mimicking kuji-kiri. Kuji-kiri is an aspect of kuji-in, known in English as the Nine Hand Seals, a meditative practice of placing the hands in various positions while repeating corresponding mantras. Originally an ascetic Chinese Taoist technique designed around self-centering, it has evolved in meaning throughout history, absorbed into various Japanese religious sects such as the Shugendo, who dedicate their lives to the ultimate of gaining a spiritual, supernatural power with which save themselves and others.

Kuji-kiri, which the Shugendo use, involves moving the hands in a series of straight lines on an imagined grid, to cut open a path to the world beyond the illusionary one we live in. In other words: the world of spirits. And if a path can be opened, then surely we can interact with the other side.

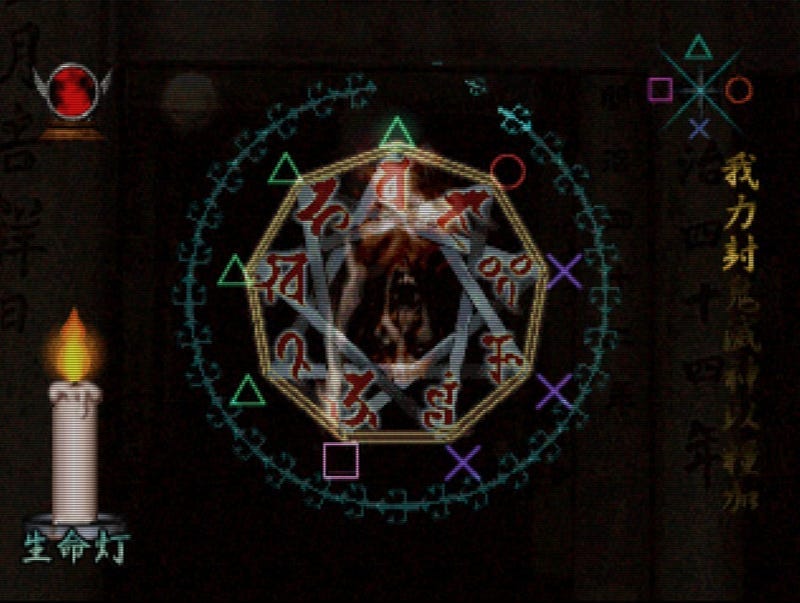

To digitally recreate kuji-kiri in-game, a sealing circle appears over the spirit after completing enough QTEs. The player must then press the corresponding face buttons which line the circle before time runs out, at which point one “cut” will be completed (along with a voice shouting the corresponding character of the mantra) and a new circle will appear with a new set of button prompts. This continues until either all nine of the seals are completed or the player fails one.

The idea is that the button presses mimic the straight lines drawn with the fingers. While decisively visualized in-game, there is also a physical element, the player naturally mimicking the movements with their thumb. Technology, body, and soul begin to melt together.

Mechanically, what is interesting about this decision is that the button presses are never randomized. Throughout the entire game, every single exorcism plays out exactly the same. The same buttons, the same order, the same time limit. On paper, it sounds tedious, realism undercutting the escapist possibilities of games, but in practice, this consistency only furthers the game’s strangely meditative effect. Intentionally or not, the original goal of kuji-kiri and kuji-in creeps back as motions and mantras slowly dig themselves deep into your muscles and brain, the rest of the world falling away in the face of simple repetition.

In an incredibly smart move, the game’s difficulty is scaled to accommodate this, gradually increasing the number of seals that must be successfully completed as the game goes on, mimicking the natural progress made from repeated exposure. With this, a balance is struck, a tension and atmosphere emerging from gameplay systems that never fall to frustration.

But answers give birth to problems, and as Media Entertainment finished developing the bones of their yet untitled game and implemented the photographs they had received, they found themselves facing an issue they had never considered. One which threatened to doom the entire project.

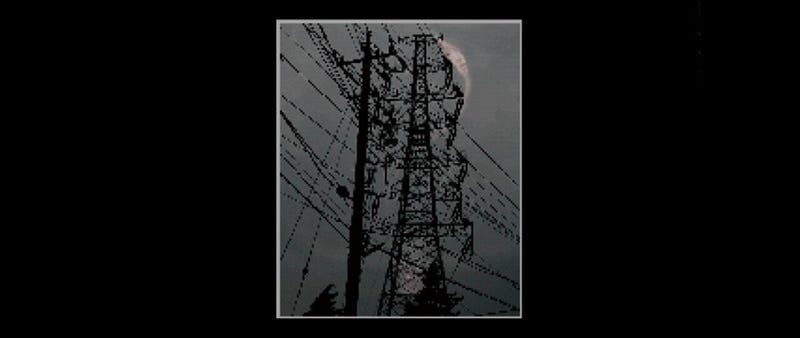

Visibility. Ghosts in spirit photographs are subtle, obscured in shadows or nothing more than the vague suggestion of form, or hidden under a multitude of floating orbs, all of which is only compounded by the drastic loss of clarity when filtered through the PS1’s low resolution displayed on a CRT screen. Spirits were all but impossible to find; the dead erased by technology.

With this, doubts of the practicality of the project began to spread within Media Entertainment. It seemed, like so many great ideas, to be impossible to realize — a dream innately incompatible with reality. Worse, the weather was changing, a sign of their approaching deadline, leaving them with neither the time nor budget to restructure the game to account for the lost fidelity. There was one solution, but it was one they were afraid to suggest, which nobody wanted to admit.

The photos were real. It was undeniable. So why not change them a bit, just enough so that they would fit into the framework of the game? When the company president finally suggested the idea during another meeting, a great wave of relief and support washed over the team, the broken promise of their original vision exposed and given form. By tainting the purity of the game, everything would be solved.

K-Kawa resisted, of course. But the collapse of his vision by the hands of others was inevitable, the entire company supporting the decision, so he acquiesced on the single condition that no matter what they did, they would never fake a spirit.

At first, the changes were minor — color correction to better highlight a ghost, or erasing noise and unwanted light orbs from the image. But though they technically remained true to K-Kawa’s request, the team quickly became more and more liberal with their edits. Spirits stretched and enlarged, touched up and moved around, even cut and pasted from one photo to another. Freed from their self-imposed constraints, the already shaky scale of reality and fiction began to fall ever deeper into the latter.

But at the same time, unease welled-up among the staff. Though few of them explicitly believed in the existence of spirits, the cultural footprint of the dead, the way this belief permeates society at large through fiction and religion and programs like Anata no Shiranai Sekai, was impossible to ignore. On some level, they saw their work of cutting and playing with ghosts as blasphemous, immoral.

Because of this, much of the staff took vacation days they had never used. One employee who had been with the company from the start retired midway through production as they had become increasingly depressed from the work. Some reported having nightmares of angry ghosts visiting them. The boundaries became weaker: the physical world and the spiritual; work and freedom; all of it melting together.

When popular fighting game Mortal Kombat 11 released in 2019, reports emerged that several of the animators and model designers had developed PTSD during development. Working day in and day out on the depiction of hyper-violence, watching real gore, simulating blood, spending days animating nothing but a spine being removed from a body, they found themselves having strange dreams and intrusive thoughts. One mentioned that when he looks at his dog, all he sees are the guts and viscera inside of it. In content review farms, the businesses that review material flagged inappropriate on social media, employees regularly become severely depressed and exhibit signs of trauma. They start to see the world differently, unable to escape from the violence of their jobs. They can’t watch movies anymore; they can’t look at a child without crying. Their work ruins them.

And although Media Entertainment was not submerged in images of violence, they did exist in a culture entrenched in media, beliefs, and ideas of spirits, one which saw their work as dangerous and wrong. It is easy to imagine the stress born from this, even if they didn’t consciously believe. Work has a way of infecting life — when one spends a majority of their time with a job, it will attach onto everything else like a parasite.

Eventually, working through the stress and unease, the team emerged with a completed alpha build of their game. With the structure and gameplay finally in place, finally resembling a real product, voice actress Junko Noda was brought into the studio to record dialogue for the story.

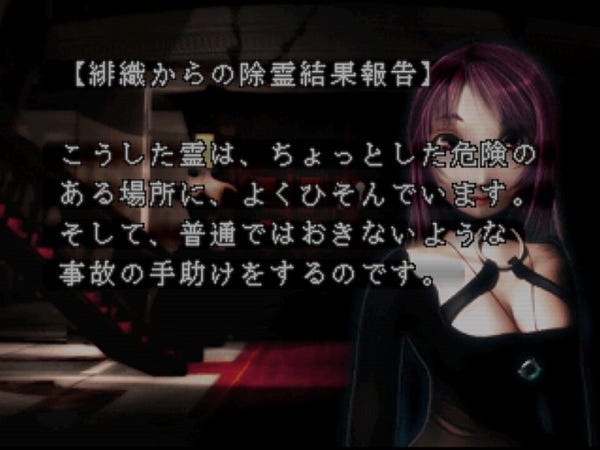

Told through visual novel styled cut-scenes, Noda plays Hiori, a young spiritualist, revered for her incredible abilities at exorcising spirit photos. Perhaps naturally, because of her powers at seeing the dead, she has become a hikikomori — a shut-in refusing to leave her moody mansion. Most of the game is thus spent exploring the desperate letters and pictures sent to Hiori, each photograph turned into a short horror vignette, with small pockets of information about her told between chapters (each chapter a collection of three photos). It is, like the gameplay itself, very structured. But gradually this structure collapses as Hiori’s past and the past of her family returns to her after receiving a letter about the ghost of a boy she once knew, history bubbling up like another spirit and upsetting the safe repetition she has built for herself.

It’s a short story told quickly and with little embellishment, but the architecture of it is interesting, funneling strongly into the mechanical experience of playing the game itself, and Junko Noda narrates the entire affair with the quiet, near dispassionate energy of a ghost story, told on a summer night, voice like an unnatural breeze upon your neck.

Once the lines were recorded, everything finally in place, the entire team dedicated themselves to rigorous play-testing. There were only a few months left. With such a small staff, they had to hire part-time help, high schoolers who would come in when they could to test the game. Already long work hours turned obscene, many employees spending the night in the office. Those nights only compounded the unease of their job, surrounded by ghosts long after the sun had set. And while paranoia slowly grew, so too did their relationships with one another, co-workers becoming the only living people they would see and interact with. Media Entertainment began to isolate itself.

A few days later, the noise started.

An awful whine, consistent and high pitched, like a sine wave or nails on a chalkboard. Nobody knew where it was coming from, only that it had started when one play-tester finished the sixth photo, and that it kept getting louder and higher pitched. Everyone stopped what they were doing to search the office to find the source of the noise, but to no avail. They developed splitting headaches as it grew. It was so loud. It could be heard outside the building. Not long after it started, ever-rising in pitch, the noise became so high that nobody could hear it anymore. They never found out what it was. Nobody knew it ever stopped.

Sound in Kowai Shashin is sparse. There are only a handful of songs, most of which err on the side of ambiance and sound effects are similarly short and to the point. While searching a photograph, a droning ambient track will play, punctuated by loud, empowering shots of noise as you exorcise a spirit. The same songs play over and over, the same sounds repeat themselves. And though the sound library is small, it is strong, presenting a palpable sense of horror.

Shortly after the noise, just as everything was settling back to normal, the planning director collapsed while testing. His eyes were pulled back wide, his teeth chattering as if they were freezing, controller gripped firmly in hand. At the hospital, it was diagnosed as an epileptic fit, and Media Entertainment found yet another problem dropped onto them.

Being developed only a few years after the infamous December 16, 1997 episode of Pokémon, which featured a sequence of flashing lights that hospitalized over 600 children, the company had no choice but to drop and search for the cause. They could not afford even the possibility of an event like the Pokémon episode, one which caused an enduring public outcry, lasting changes to television and animation production, and has been mocked across the world.

Luckily, the planning director’s epileptic seizure was deemed minor, and he could rest at home. It seemed to everyone just another addition to a growing series of unlucky setbacks. But in less than a day, that view would change, and Media Entertainment would find itself submerged in a nightmare.

The next morning, they received a call from the hospital. The planning director had been readmitted. The night he went home, he went to his kitchen, took out a knife, and cut off his thumb. He remembered doing it, perfectly conscious as he sliced through flesh and bone. But only after, as pain overwhelmed him and he writhed on the floor, did he realize what he had done. And no matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t remember why. But his co-workers knew. How could they not, when they heard what had happened, when they heard what thumb he had cut off? It was the right one; the thumb used to exorcise ghosts.

Whispers of a curse spread throughout the office. Speculations on who would be next. They would not have to wait long for an answer, as a few days later another play-tester, one of the part-time high-schoolers, collapsed, just like the planning director had: eyes wide, teeth chattering, hands gripped to controller, the sixth photo in front of him. Waking up in the ambulance car half-delirious, he told the paramedic what had happened.

A mistake during one of the kuji-kirin — a missed button pressed, a failed exorcism. The next time he pressed a button, an overwhelming, high-pitched sound filled his ears and his eyes went white. Even though he could feel them open, he could see nothing. Hear nothing. Only white. White and the noise. The next thing he knew, he was waking up in the ambulance.

The whispers turned to yells. Something was wrong. One programmer reported waking up in the middle of the night, unable to move or breathe. Several developed migraines headaches that wouldn’t go away. A third play-tester, this time working on the eighth photograph, heard the noise ringing in their ears before developing a nosebleed that wouldn’t stop. Scared for their lives, a level skip was implemented, letting the staff avoid testing the most dangerous photos, pretending they didn’t exist. Concerns of an incomplete, potentially dangerous game grew as the staff of Media Entertainment became increasingly paranoid.

A spiritualist was brought in to perform exorcism rites on the company building. Many began spending their spare time at temples, seeking the help and advice of priests. Others started repeating the mantra spoken by Junko Noda. They prayed to her, and to the protagonist Hiori, the invented girl who could destroy ghosts. They saw Noda as their savior, as the one keeping them all alive.

Like many successful voice actors in Japan, Junko Noda has had an incredible career with well over two hundred voice credits, multiple albums, and innumerable appearances in public and on media, resulting in a strong, loyal fan following. Devoted fan followings are a well-known aspect of Japanese media. Much has been made about the bizarre, unhealthy, exploitive fan practices of anime and idol culture — worlds where consumers are encouraged to buy the same CD over and over again and where handshakes cost money. And while there are innumerable issues, there is also a clear element of othering, of playing into the old cliche of ‘weird’ Japan. Aggressive fan practice is not unique to the country. You see the same fervor in fandoms and with online personalities — para-social relationships taken to frightening extremes. You see it in the West’s aggressive paparazzi culture, which preys on celebrities and forcibly tears away the separation between life and work. Celebrities are not people, at least in the eyes of popular society. They are figures and ideas. They are almost like spirits; disembodied in our mind, existing in another world that might briefly overlap with our own.

Unified under their belief in Junko Noda, the team continued, finishing the beta and moving on to the last check before the master release.

As the days turned warm and the nights long, K-Kawa stopped coming to work. It was explained to the staff that he was on temporary psychiatric leave, a brief rest from the immense stress of game development, but everybody knew that was a lie. They knew the truth: he was the fourth victim. The curse continued; work continued.

At the end of spring, on a morning mere days before the game was to be sent for printing, they received a call from K-Kawa. He sounded good. He sounded normal. He said he was feeling better and would come back to work later that day. The effect of the call was like a valve being released; the dense fog of stress and fear lifted from the offices of Media Entertainment. He was okay. They were okay. They hadn’t fallen victim to the curse. While applying finishing touches to the game, they prepared a party to welcome K-Kawa back with open arms. To welcome him home.

That evening, the news came. K-Kawa, dead in a train station, a train station going the opposite direction of work. The train station right next to where the sixth photo was taken.

The last bit of hope among the staff crumbled.

In an effort to bury what had happened during production, K-Kawa’s name was removed from the credits. Everyone who had suffered or quit during development was similarly stricken, erased from the game’s history. And on July 25, Kowai Shashin was released. They made their summer release.

Less than a year later, Media Entertainment would file for bankruptcy and close. Nobody missed them.

Or so they say. Because it was a few years later in 2005 that an anonymous poster on the 2chan imageboard shared the story of the game’s development, purportedly told to them by a former member of the staff. It spread across the internet like wildfire. A haunted PS1 game, a cursed development, a game that could kill. It was irresistible. And also a lie.

Nobody died making Kowai Shashin. Nobody cut off their thumbs or had epileptic seizures. Playing through the game, it becomes increasingly apparent that the photos are all faked, ghosts nothing more than cheap CG and poor digital effects. Even the mantra spoken to exorcise spirits is invented. There was no marketing of the game as real, and no evidence that the development was anything other than completely normal. It is and always has been, just a game.

But does that matter?

Today, Kowai Shashin is known more for the story told about it than the product itself, transcending its origins to become a certified urban legend in Japan. Looking at reviews for the game online, they almost inevitably center on its creation, of how it is cursed, how people are scared to play it. A copy today sells for over 400 dollars.

In a way, then, the original marketing plan from K-Kawa has succeeded — people crave for the game as its history has been rewritten. We have invented ghosts for it, created a story and an outlet for our anxieties of a life dedicated to working, of being forced to suffer and be harmed by the violent, inescapable hand of capital. People believe in the curse of Kowai Shashin and what never happened to Media Entertainment. It has become an inexorable part of the game — an identity taken on that was never originally intended.

So does it matter if Junko Noda doesn’t have powers, or that ghosts might not exist, or that Nostradamus was a fraud? Because it has already become true on some level, like so many other stories. War of the Worlds caused a panic when it was first read over the radio in 1938. In 2016, there was a massive spike across America of reported killer clown sightings. Two years before that, a young girl was stabbed and almost killed because of Slenderman. Ideas and fiction have a way of seeping into the public unconscious, nagging at the back of the mind, repeating “what if?”

And it is easy to say that the story of Kowai Shashin doesn’t really mean anything, that it is nothing more than a silly internet tale. How could an anonymous post about an obscure, cheap game be anything else? But stories are never just stories; ghosts are never just the dead. They are a reflection of us and our world in all of its complexity. They show us how we live.

Kowai Shashin is haunted.

All of us are.

Music of the week: Ill Bone - Shisha

Absolutely undeniable piece of gothic post-punk. It’s title, which translates to “The Dead” perfectly conjures up (along with the wonderful cover art) what sounds lie in store: heavy political funeral wails for a world antiquated and rotting, built with the architecture of our corpses. Deary and enveloping with a lot of little surprises to sink your teeth into. The last track in particular, with its muted, post-rock adjacent horn? Unreal.

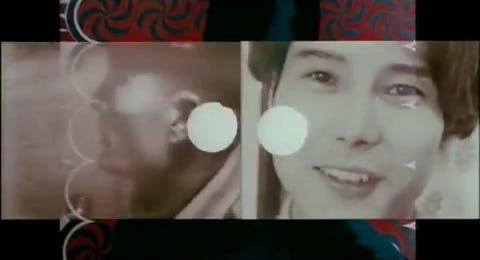

Movie of the week: For My Crushed Right Eye

Toshio Matsumoto, one of Japan’s greatest experimental directors, does what he does best here: completely melts your face off for a solid twelve minutes. A dizzying explosion of layered images that seems violently chaotic until your brain starts to catch up and you see the infinite connections being made. Made in ‘69, but its overwhelming depiction of the unending assault of pop culture and history and society only feels more relevant than ever.

Thanks for visiting! If you liked what you read, share it around! It’d make my day :)