Talking games | Mirrors

The terror and pleasure of boredom in a forgotten PC-88 adventure game.

One of the best moments in the 1990 adventure game, Mirrors, happens early on. The protagonist, David, lead singer for a successful English band, is in Paris on tour and can't sleep. It’s been that way for a while. No matter where he is or what he does, it seems like whenever he closes his eyes, he is assaulted with nightmares, bizarre dreams that seem as real as reality, the kind where you're never quite sure if you were really asleep or not. They are dreams where he is chased and dreams where he is assaulted, dreams where he kills and dreams where he burns. And the worst of it is, no matter how much he tries to escape, the roads in his mind always loop back around.

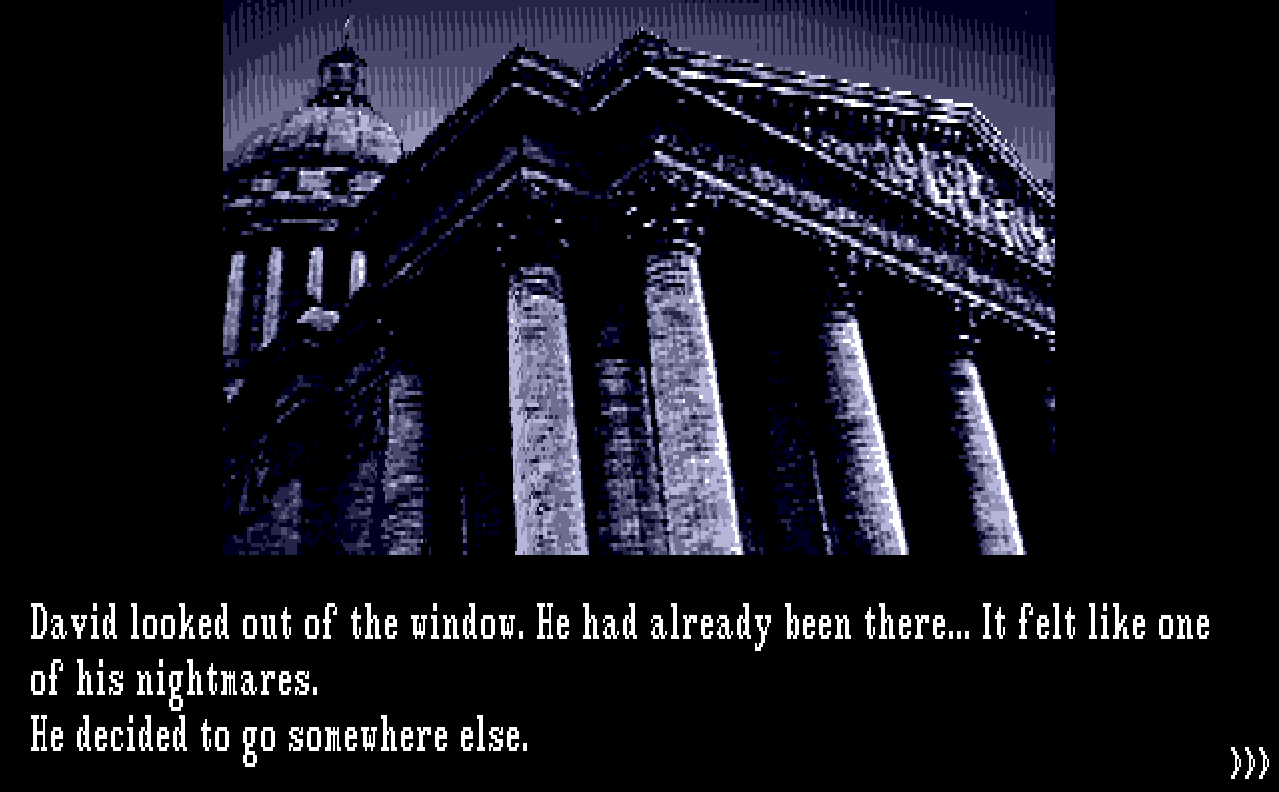

Paranoid of going to bed, David sneaks out of the hotel his band is staying at and decides to explore the city. What follows is a tourist maze of historic locales, player presented with an ever-changing list of the city’s most iconic landmarks as they are forced to drift from taxi to taxi, place to place, taking in the most rudimentary collection of fun facts. Here is the Eiffel Tower, there the Arc de Triomphe; gaze at Sainte-Chapelle and the Pantheon and the Opera Garnier. The list seems almost never ending, player selecting one after the other and yet nothing continues to happen over and over again. And for a time, it is boring. There’s no other word for it: a monotonous detour from the plot with no purpose. “What is the point? Why am I wasting my time? Hurry up and let this night end,” you think as a minute turns into five, then doubles from there.

It's only then that it happens. Exhausted of options, without any hint of progress, you select a landmark you've already seen. Perhaps it is the Basilica, or Notre Dame, or maybe the Champs Elysées. It doesn't matter, the result is the same.

Absolutely nothing. The same place, the same images, the same action. Except this time David thinks thinks about how he's already been here. He thinks about how it feels like he is in one of his dreams.

Developed by Soft-Studio Wing, who specialized in occult adventure experiences, and released for the PC-88 personal computer system, Mirrors in many ways feels like a game destined for its fate: to be forgotten and ignored, drifting quietly down in the sea of obscurity. It didn't even have much hope of being seen on release; a quick giallo-esque horror adventure game, it is often repetitive and frequently absurd, a title with camp in its bones, written with a largely spartan style as it peddles in cliches of medieval warlocks and magic that were already out of fashion when it released. It is a game that, as often as it is thrilling, dull, perhaps the greatest sin a game can commit.

Which is exactly why it is a potent, palpable reminder of the magic of art and games.

We have been trained like Pavlov’s dogs to see games through critical binaries. There is good and there is bad; buy it or skip it; play or pass. Under the dictatorship of “good” game design, developer and audience alike are conditioned to self-perpetuate a complex flatness. Don’t take too much time moment to moment, don’t be too difficult, don’t let the player get stuck, don’t have any friction in the controls, do make sure there is a loop but don’t let it be too repetitive, make sure there is plenty of side-content and DLC potential, make sure the masses can gamble their life away, but don’t step on any toes and don’t step out of line and iterate, iterate, iterate. A thousand rules for a thousand situations in a thousand games. With time, budget, knowledge and profit, the edges of titles are sanded off until wood glides smoother than metal, until you can look at a ball of oak or elm and see yourself in it like a mirror.

Games that didn’t or don’t fit these prevailing mainstream ideas of what is correct and what is not are, all too frequently, dismissed without a chance, fueling the race for every game to be the exact same, universal, perfect experience. These “failures” can do nothing but watch as their Metacritic score flounders, thoughtful criticism steamrolled into nothing but their number and audience given the power to review bomb and destroy over any perceived slight, no matter how minor.1

“It’s aged badly,” we say about titles once praised as classics. “We don’t need the past anymore. We’ve moved on. We have now.”

It’s in that swamp of imperfection that Mirrors lurks. If, like its title, the game really is a mirror, then it is one invented before history, dull and molded and rusty so when you look what you see is only the vaguest outline of you, a distorted blotch of skin color hovering.

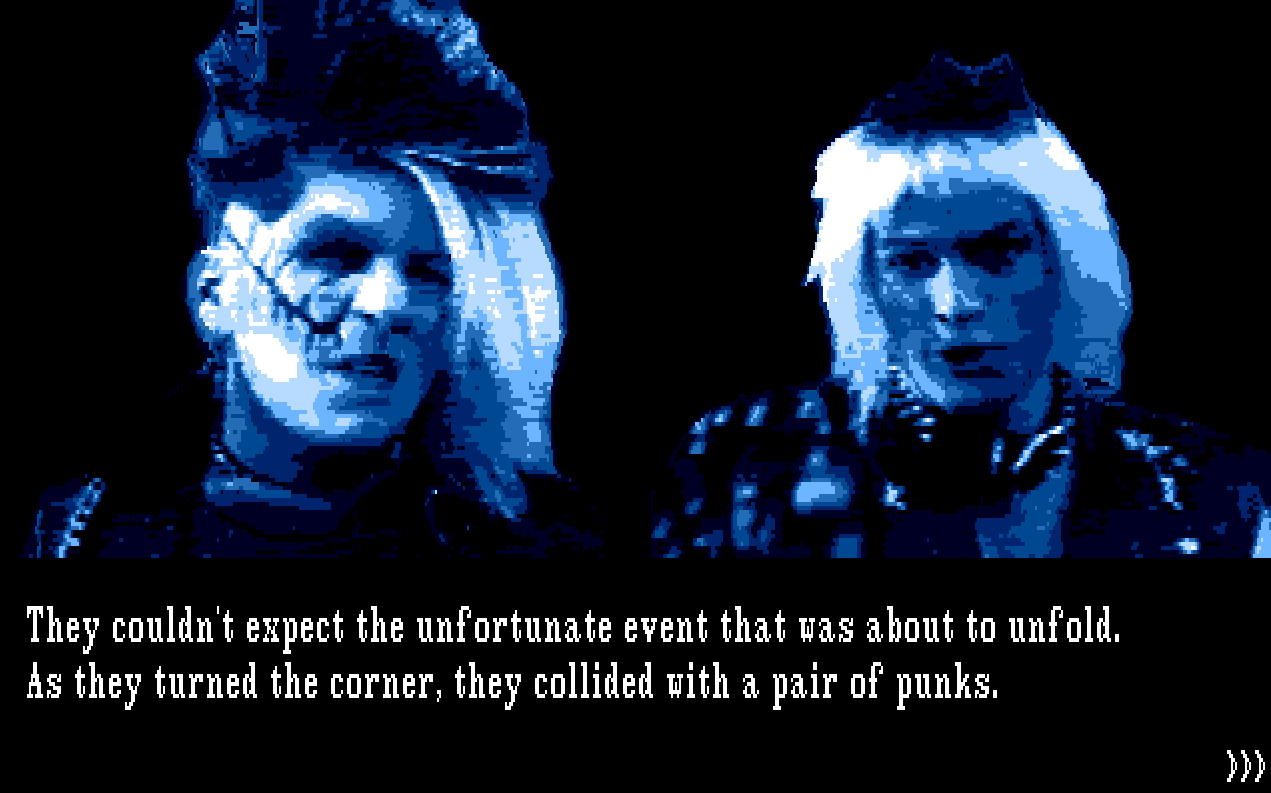

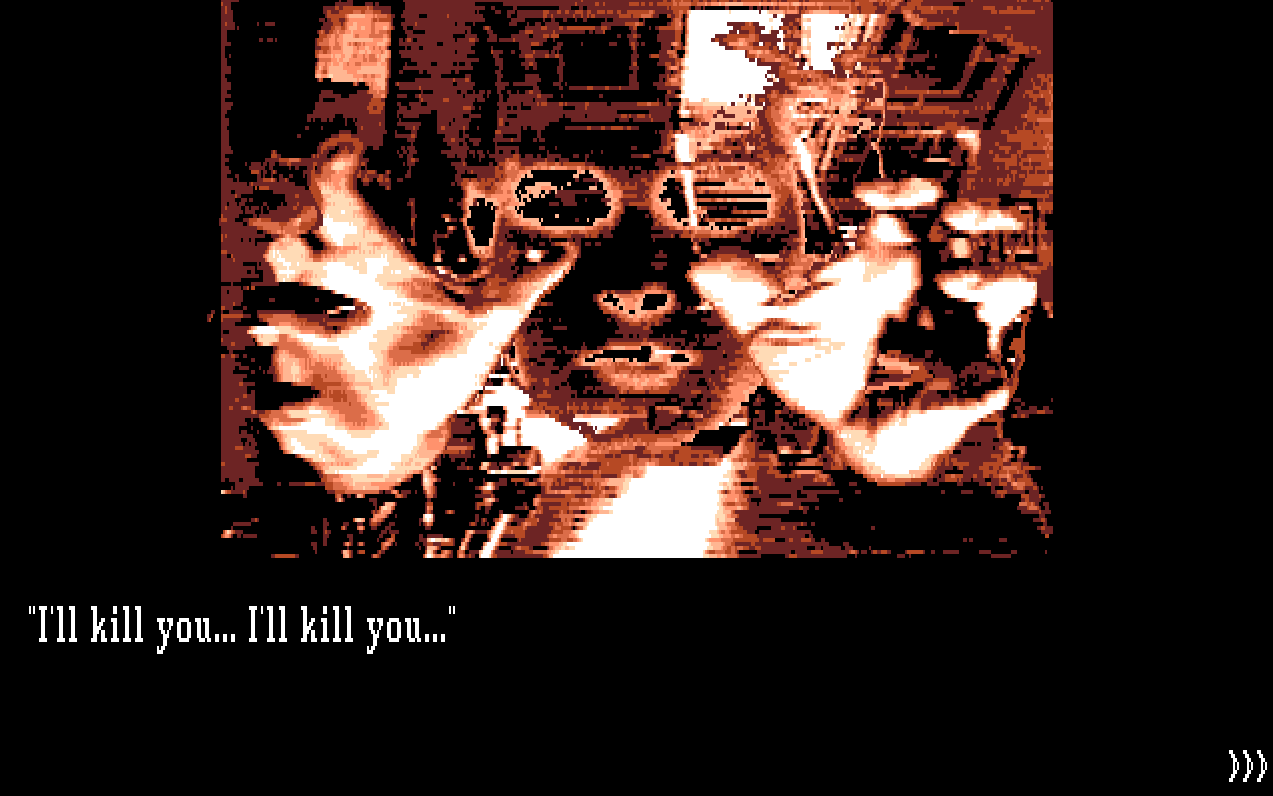

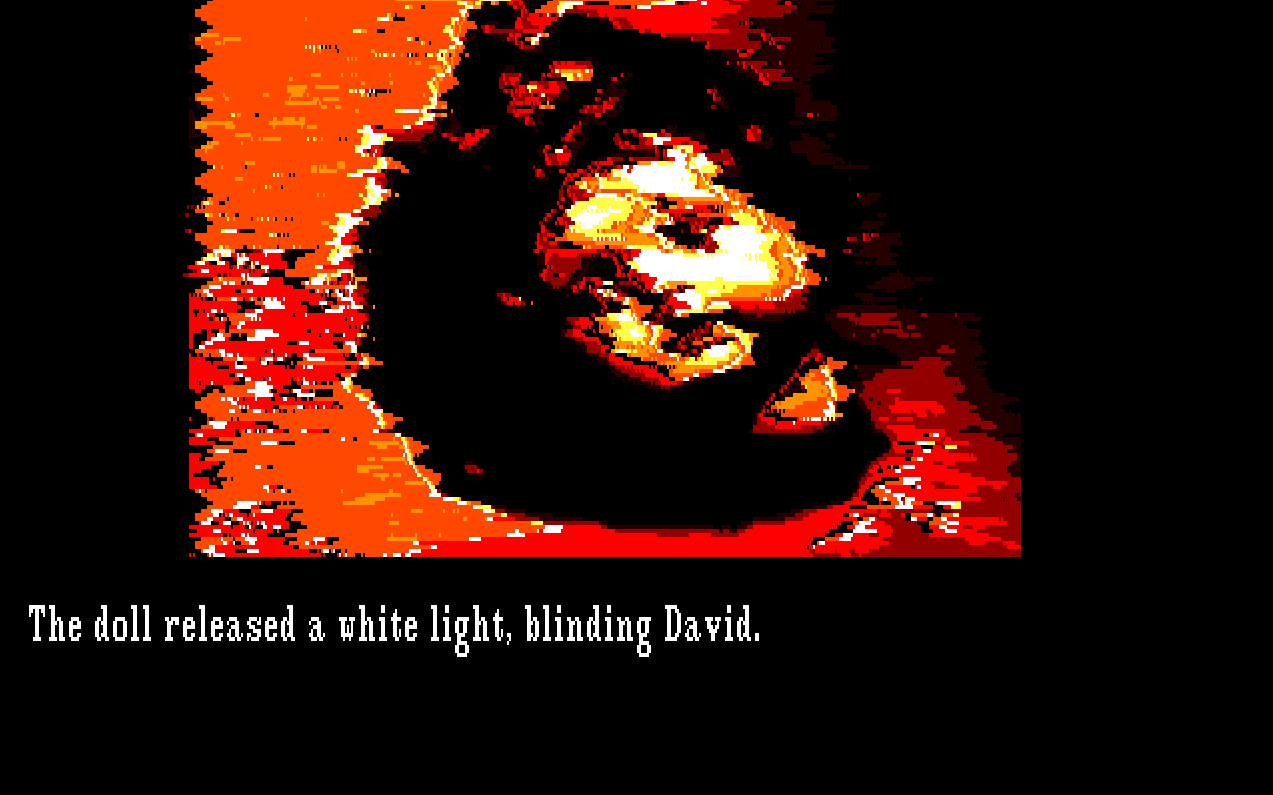

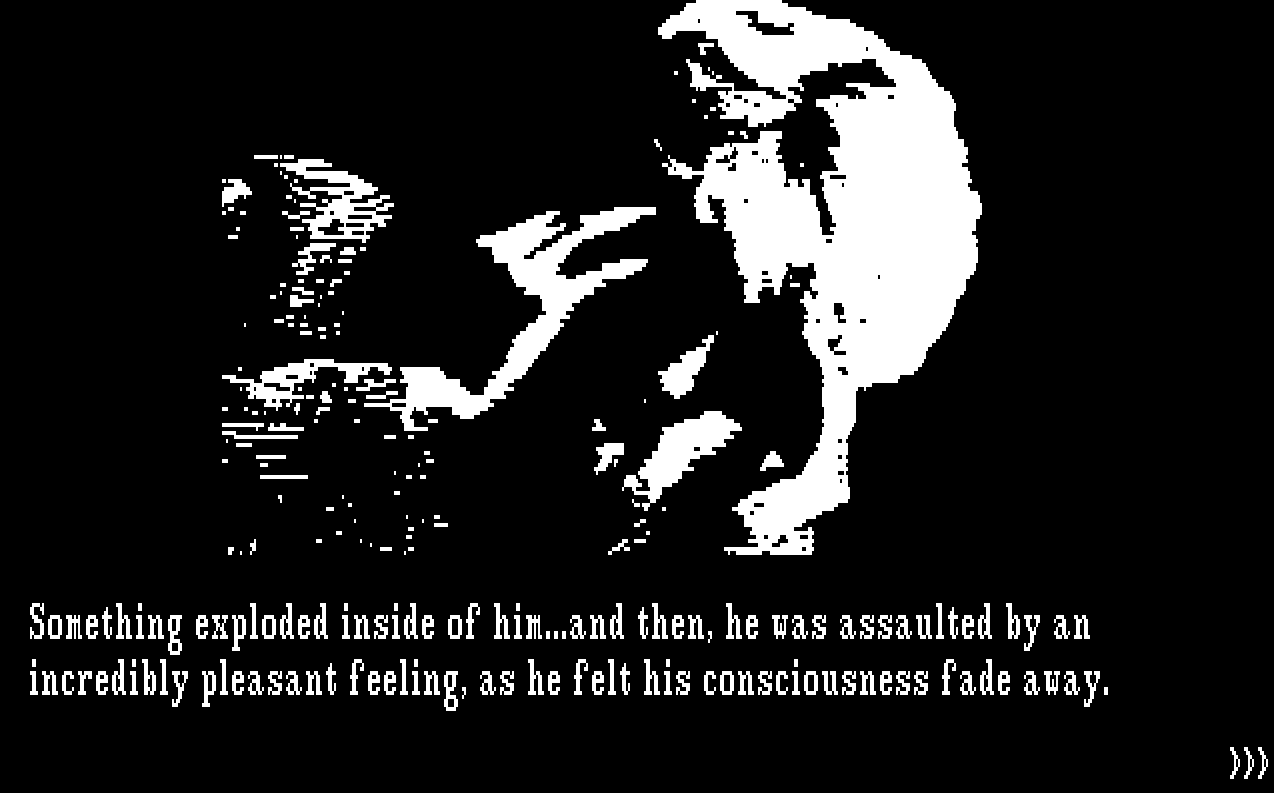

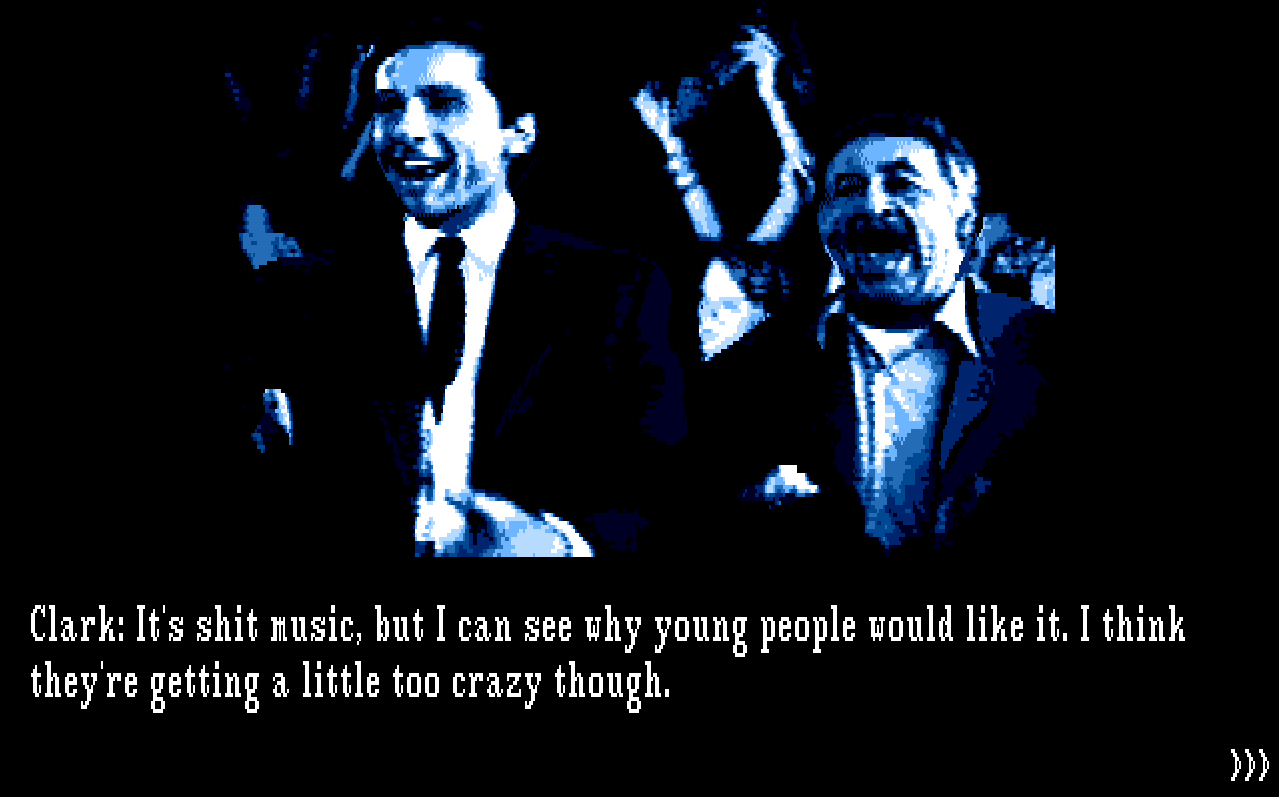

Rendered through crunchy digitization, Mirrors’ aesthetic feels at once quaint and radical. One second you are staring at FMV stills of the most stereotypical theater-kid impression of a gang of punks, tension sucked by camp supreme; the next and the colors have all gone funny, picture melting in a pixelated sludge of abstracted horror rendered half-real. Disembodied hands—made disconcertingly realistic thanks to the style—reach out towards the screen, faces float in empty voids, blood pools into oceans, searing red burning holes into scenes dominated by an impressionistic blue. Frequently, owing to its technical limitations and resolution, it manages to perfectly capture the sensation of not quite being able to make out what you are looking at in the dark. Are those eyes, or lights from the computer? Is that body, or a shirt left out? Through all of this, a MIDI Erik Satie drones on and on in the background, starting and stopping without ever being allowed to finish. It’s all a perfect match for a game whose writing is largely anonymous and bordering on amateur but which hides moments of evocative poetics behind its simplicity.

That moment in Paris is stunning. It made me sit up in my chair, game forcing player to experience what David experiences—the tedium, the frustration, the confusion and the paranoia.

I have dreams like that too, those ones where everything keeps repeating, just as I have moments in my waking life like that. Who doesn’t? Déjà vu can hit heavy at the most unexpected times, sometimes so strong that you can feel the inside of your head become fuzzy. Repetition constantly consumes our lives until a migraine creeps into the back of an eye. It’s boring, it’s repetitive, it’s “bad” design. It’s honest.2

As the game progresses, moments like the one in Paris only increase. It doesn’t take too long before the entire game is an unending cavalcade of David waking up, then waking up again, and again, and again, and again…. Reality dies as dreams come alive, both invading each other with just enough plausible deniability to remain suspect. Which one is which? What happens and what doesn’t and who knows what?

Susanna, the beautiful new assistant to the band who shows up after their previous dies, certainly knows something. Tailed by two detectives, Clark and Vince, who act as a sort of buddy cop Greek chorus to the unfolding events, she quickly inserts herself into David’s life, providing him with a steady stream of pills that will help him sleep. Sometimes they work, sometimes they don’t; either way, it’s only a few days before he is completely dependent on her.

And so the game continues with a rhythmic repetition both structurally and mechanically, where the player is asked to select each person before they talk, turning conversations into a slow, intentional series of keyboard presses and David keeps waking up, the same image—an out of focus eye—and the same sound cue reappearing ad nauseam. Things happen, but little of it suddenly, Mirrors content to return to sight seeing tours of countries just as much as nightmare horror of witch burnings. There’s no skipping, no fast-forwarding. When the game needs to load, it takes minutes. Any major publisher would balk at this, these forced leisurely digressions of no importance, this almost maddening patience. They would cringe and recoil because games are above all else about play, about fun, and we have created scientific formulas for what that means.

At one point in the game everything halts for a complete, four-minute, voiceless music performance from the band, lights throbbing in multiple colors, the crowd collapsing amongst the flashing light into an indistinguishable mess as David’s vocals are rendered as text on screen. In game, the band is a hit; the music is so powerful that it at one point causes the audience to being ripping and peeling their faces off in a ravenous frenzy. In real life, the song isn’t very good.

Which all leads to the big question, the one everyone wants to know. Is Mirrors a masterpiece? Is it some forgotten diamond in the rough, waiting to be rediscovered? Is it even good, really?

Who cares. It exists.

—

Music of the Week: Doji Morita - A Boy

You’d be forgiven looking at the cover of A Boy and thinking, like I did, that it contains nothing more than cornball ‘70s hard rock. But I’m here to tell you, you could never be more wrong. Morita, with one of the most beautiful voices you’ve ever heard wanders through a collection of equally beautiful folk ballads that fling you with the force of a rocket into a world of pure, overhwelming melancholy, regret, and resignation. Lush, ethereal laments that capture those sad feelings as perfectly and honestly as you’ll find. A real night album if ever there’s been one.

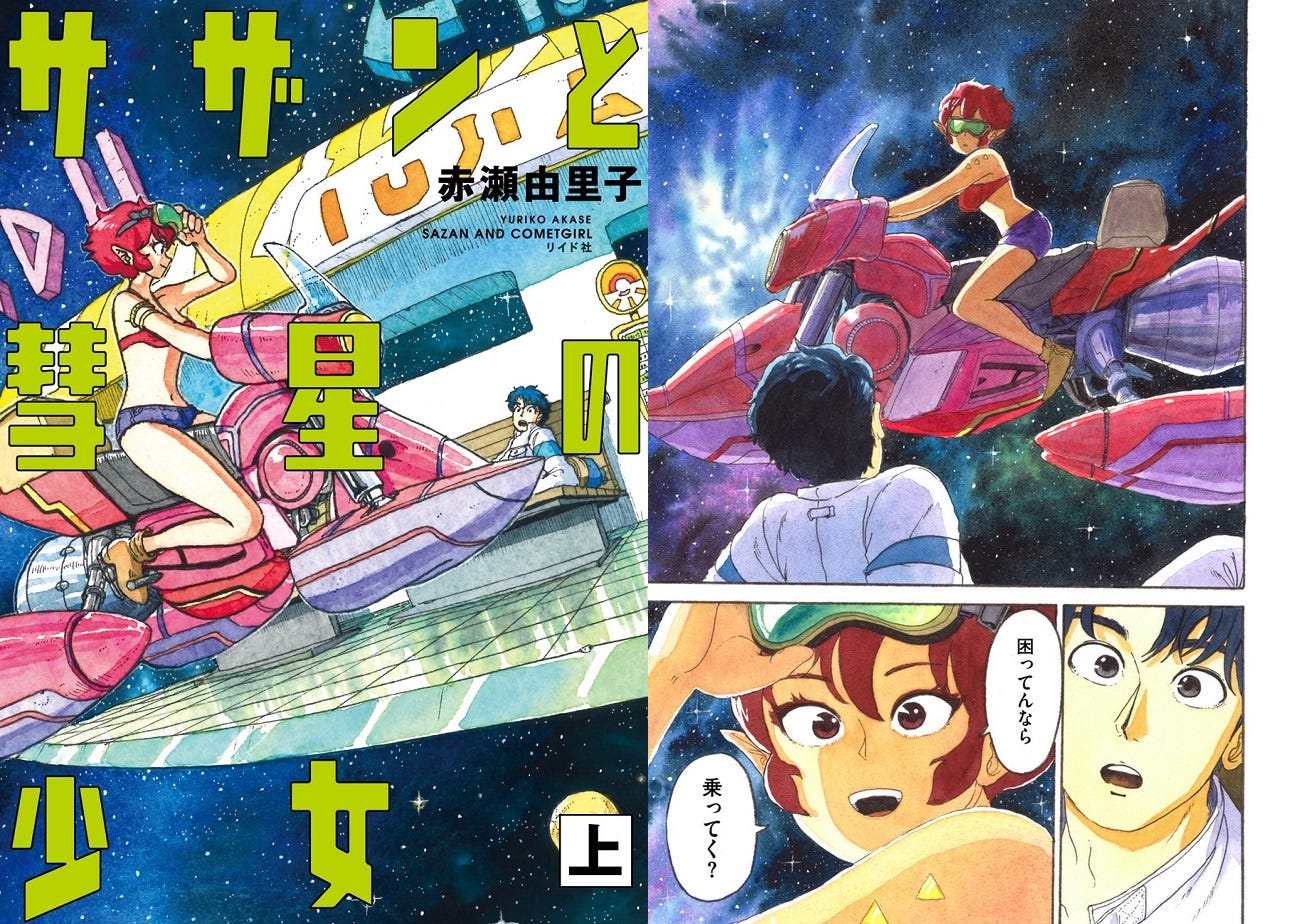

Book of the Week: Sazan and Comet Girl by Yuriko Akase

Yuriko Akase’s intentional 80s throwback, in particular to sci-fi comedy classic Dirty Pair, is an overwhelming delight: breezy and tightly made and light as air as it barrels through a galactic adventure of endearing characters, charming comedy, and cinematic action. It’s also absolutely, jaw-droppingly gorgeous, rendered entirely in stunning full-color that perfectly encapsulates its lively, romantic energy. It’s in color because it is the kind of story that makes you see the world in color. Fun, fun, fun!

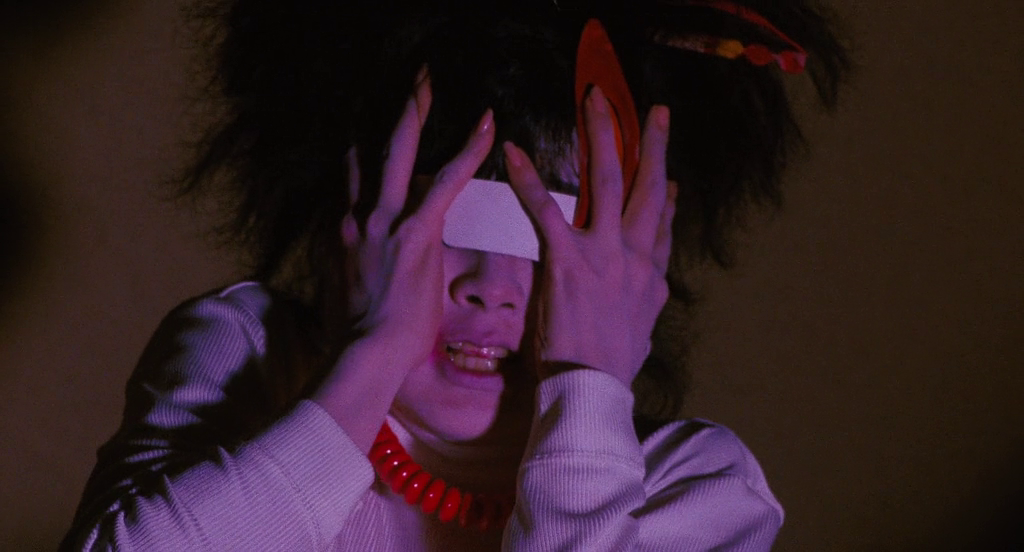

Movie of the Week: Luminous Woman

Shinji Somai’s films are all intensely distinctive visually, but even then Luminous Woman is something else: an operatic epic of nature and concrete, death and expression and the impossible battle to truly understand another person, all bathed in deep purples and pinks. Much of the story is set in these surreal, impossible places (most notably an underground fighting ring where jesters dance and an opera singer croons while men dressed in bear suits beat each other to death) but even when it isn’t, it feels like you are in another world. One of the great director’s less seen movies, but that certainly doesn’t make it a minor work. P.S. Also features THE greatest phone call scene in cinema—like for real, an actual tour-de-force landline conversation.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here’s a monumental video about Gundam, dress, and the body