Talking games | Ridge Racer V

The weight of the millennium.

I don’t like cars much. Never have. They’re death boxes — strange machines that force you to relearn how to walk with a labyrinth of new rules to keep in active mind and if you don’t then your flesh is forfeit. They are the perfect nightmare for the anxious teen that I was, the kind of person who wonders and worries if they fully exist in the world, if strangers can really see them at all, if others will drive right through them when crossing the street because how could they be expected to notice a ghost like you? The way I always figured, cars are solid. They have weight. They’re no good for someone as light as me.

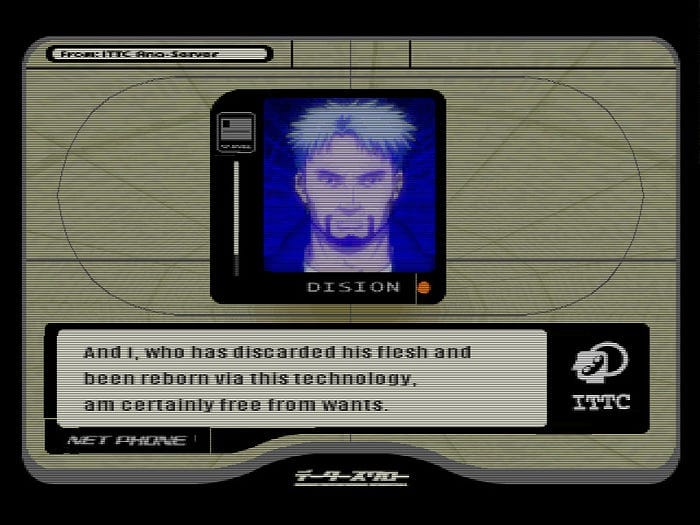

In 1999, legendary video game publisher Namco released the third entry in their arcade leaning flight sim series, Ace Combat 3: Electrosphere. And while the previous two titles were successfully high octane military dogfight excursions, there was something different about this new one. In contrast to the established Top Gun-esque vague hoo-rah warfare, here was a game pushed deep into the future, envisioning a Definitely Fictional And Not Real cyberpunk world where corporations have become militarized nations. The game is a startlingly prescient exploration of politics and identity in the information age, one where characters dream of shedding their flesh and replacing their bodies with the planes they pilot, where the delineation between machine and man has blurred into nothing, where the internet and a new millennium signal a shift in the definition of human that is both amazing and terrible. It is, as far as I’m concerned, one of the masterpiece works of Y2K internet paranoia, a towering achievement in our anxieties for the future. (I wrote A LOT about this game a few years ago — it’s like an all-time top 3 title for me — so go read that for more)

A year later and the new millennium Electrosphere was so anxious about had arrived. And with it, a new game from Namco.

Ridge Racer V.

Released in 2000 as a launch title for the then new, soon to be monstrously dominant PlayStation 2, Ridge Racer V was made to rush in a new age, a new thousand years of infinite possibilities, a new console when new consoles had some kind of meaning. New, new, new: new future, new world, new time. And boy does it do just that.

Ridge Racer V has weight. It has conviction. Under its hood of shining metal burns an engine soul, an idea, a belief. It is a disc, it is code, it is a programmed logic system in a silly little console, and it is, in that way and in its own way, the boots on the ground actualization of Electrosphere’s philosophizing on the blurring distinction between human and machine.

Ridge Racer V lives more than I ever have.

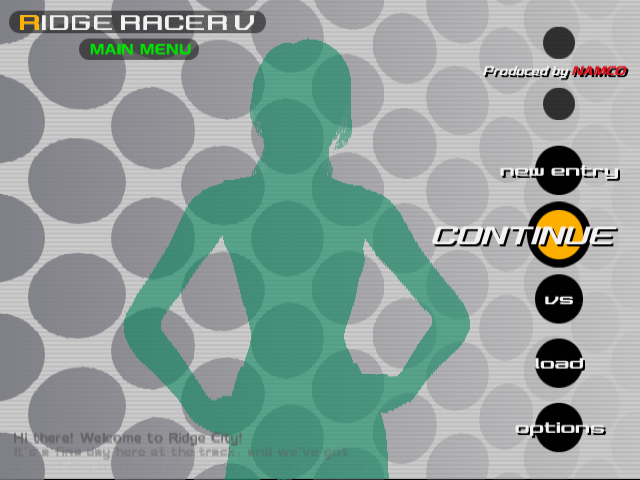

The previous game in the series, R4: Ridge Racer Type 4, is deservedly considered a high point of the first Playstation, an aesthetic miracle in game form. Namco at this time were the absolute kings of video game UI, of turning menus into profound tonal expressions and games into cohesive works of pop art perfection. With a story mode told in the color of yellow humanizing both the teams of people never seen behind the wheels who are all dreaming of a better future, hoping for a way forward from pain of a thousand kinds built up over a thousand years, Type 4 turned the racing game into a mode of expressionist humanism. Pile on top of that its ethereal celebration of the end of the 20th century — aestheticized through cars that feel like they float above the ground as if steel ghosts, hazy streetlight soaked city nights, and taillights drifting in long streaks across empty highways — and you have one the great tonal experiences of all gaming. Which makes following it a tough ask.

Ridge Racer V is in direct conversation with its iconic older brother in the same way I believe it’s in conversation with its sibling in the sky, Electrosphere: with an embrace of thematic concerns and a rejection of distanced philosophizing.

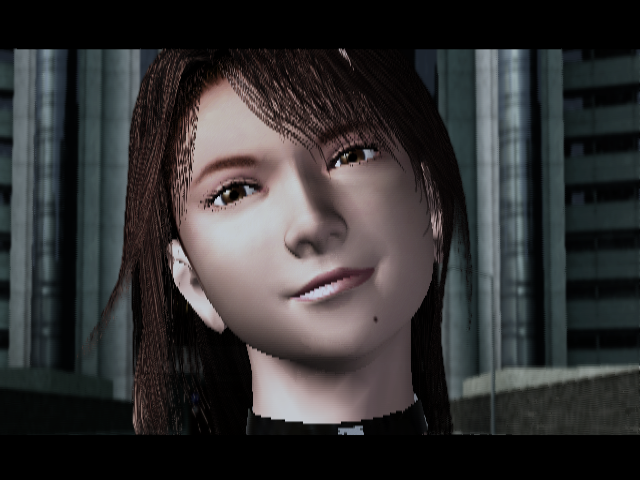

You see it the second you turn the console on. Where Type 4 features maybe the peak of Ridge Racer’s history of CG intros (honestly one of the coolest and sexiest films about cars ever made) the fifth entry breaks hard from tradition. Idol and mascot of the series Reiko Nagase is gone; the patient pace and poetry dead; the smooth CG murdered. In its place is someone new, someone young and with an altogether different, more aggressive energy, caught only briefly in an explosively short minute of action backed by blaring music from Boom Boom Satellites all told entirely with in-engine graphics. To go from the previous entry to this is like being shaken and screamed awake.

“The past is dead,” it shouts. ”Welcome to the new age.”

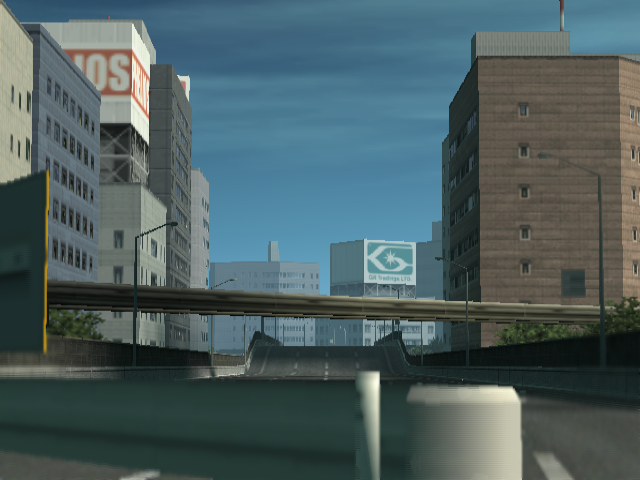

Ridge Racer V is jagged to the bone. Given in fully to the PS2’s most known visual defect, harsh aliasing (or jaggies — think how in games sometimes what should be straight lines come out looking like a broken series of cliff edges), the title roars with an unobscured energy, any pretensions or veneer stripped away for the rough core, its interlocking tracks of a city bestowed an almost hyper-real edge befitting of blue steel and asphalt, like you cranked the sharpness slider of life up a little too high.

That on its face graphical quirk of its platform is important part of the game, I think, because beyond everything else, Ridge Racer V is also maybe the purest expression of the PS2 the console ever produced. Today, video game consoles exist in a sort of soup. They are different but the same, variations on the same computer with a different skin. What exactly is the difference between the PS5 and the PS5 Pro and whatever all the different types of Xbox’s you can buy now? Hardly a thing is what. But it wasn’t always like that. Blame nostalgia (I’m sure it’s responsible for this rant) but I swear you can feel the difference of consoles of that era, each defined by different constraints, advantages, aesthetics and exclusives. So you can see those ridges and see it as a flaw, something to be fixed with upped resolution in modern emulators, or you can sit with it and find its own beauty and meaning that something smoother never could.

And the game certainly is beautiful. The more time you spend with it, the more it reveals its subtle perfection of style: the scrapping of metal on asphalt as cars careen around corners, the way their lights don’t linger but dash across the screen, the sky of infinite blue possibility peeking out from glistening buildings…and the unlock screen, that wonderfully rare cinematic reward when you finally push past your limits and find first place. I don’t know how else to say it: the scene is erotic. It’s pornography for people who want to bone their vehicles. And honestly? I kind of get it. Engines and cars are held up like holy relics in pitch black voids; camera gliding along their surfaces in extreme close-up, music reverent strings that then explode into stereo cracking breakbeat. The power and elegance of these machines and their designs, the absolute potential lurking under the hood or flowing through pipes comes rushing at you with a genuine sense of profundity. It is the very first time I’ve ever understood cars as beautiful aesthetic objects.

All of this visual clarity and comparison becomes doubly important when actually playing the game, systems tuned to beautifully reflect its comparatively pared down, raw aesthetic. Because look, Ridge Racer V is as aggressive and as mean as its jagged, roaring exterior might suggest. It’s the only way it could be as alive as it is.

R4: Ridge Racer Type 4’s opposing cars feel like the game looks—like ghosts of the past drifting towards an unknown future, these machines of an entire millennium that is about to end. For much of the game, they might as well not exist at all, harmlessly faded away in your rearview mirror, which is such an interesting, evocative choice in a game that cares more about the lives of those involved with races more than maybe any racing game out there.

In V, those same cars want to kill you. Vehicles here are more like how I know them: violent and loud. They aren’t ghosts anymore. I’m still not entirely sure if they actively have it out for me of if they are simply programmed to move along the exact routes you the player want to, but either way, opponents won’t even pause to bash your tail as you’re drifting to send you spinning out or violently insert themselves an inch away from you as you try to pass.

That loving attention to the people behind the cars in Type 4 is gone. Here, the cars are the people. Just like in the future predicted by Electrosphere, the separation between the two is silly and outdated, V seems to say. There is no story mode, no characters (with the notable exception of a radio DJ — a disembodied voice filtered through technology) here. The ghost is in the machine now; the consciousness has been affixed to metal. I see that yellow car that keeps hitting me and passing me and stealing my chance at winning and I hate them. I respect them. I know them.

All of this serves to make a game that after hours and hours still has me sitting up straight for every second; still has me hooting and hollering in every single race; still has me unconsciously leaning into the TV so much that you’d think I want to be swallowed up by it. When playing Ridge Racer V, the distance between game and player vanishes in a gleeful burst of exhaust smoke. In those moments racing, I shed my flesh and become not only the game, but the digital car, violent and free, holy and profound.

My existence is still a light one. Though my presence might not be that of a ghost, I certainly exist far from the hardness of concrete or steel. My feet don’t grip the earth or spark at the ground like the cars do in Ridge Racer V. But I have gotten heavier the last few years. I’ve become more solid. I no longer think everyone is staring and laughing, or that they can’t see me (except on my worst days, but we allow that). I can cross the street confidently now.

I’ve started to like cars.

Music of the Week | Kimitachi no Kureta Natsu by Yukiko Tanaka

An obscure bit of early 90s pop still holding onto the then fading whispers of city pop dedicated entirely to summer (as implied by the title, translated as “The Summer You All Gave Me”), Yukiko Tanaka delivers in spades exactly what’s advertised: a perfect summer listen in all the forms that might take. Sometimes melancholy, sometimes ecstatic, and always with an incredible ear for melody and willingness to luxuriate in say, a horn or harmonica solo. The first track especially hasn't left my brain for weeks.

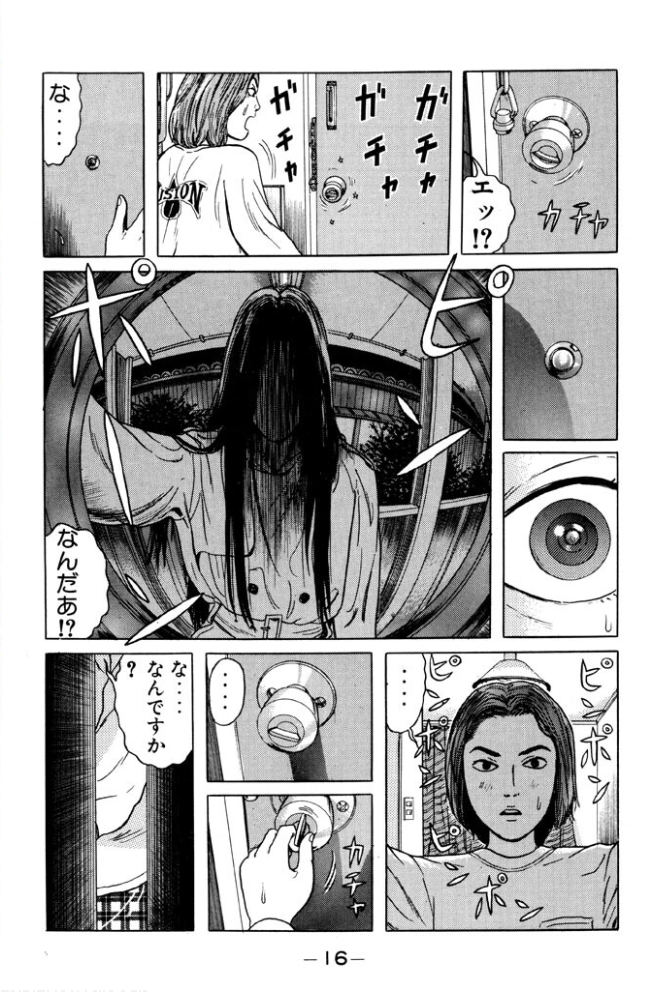

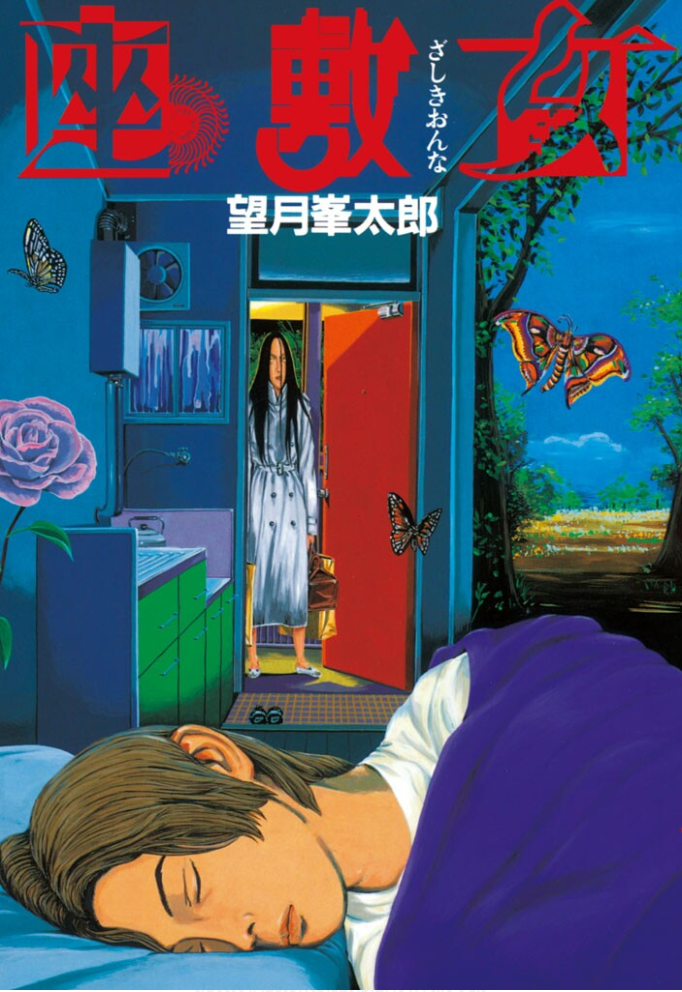

Book of the Week | Zashiki Onna by Minetaro Mochizuki

Most known in Japan for his youth comedy stunner Batan Ningyo and in the English world for the post-apocalyptic nightmare Dragon Head, Zashiki Onna finds artist Mochizuki working somewhere in the middle of the real and the fantastic for a masterpiece single volume chiller about a college student who accidentally gains the affections of a strange woman who just won’t leave him alone. With pitch-perfect pacing, snappy dialogue, and a style that manages to lean towards realism while also being incredibly hip, the craft alone makes this a book hard to put down. But what pushes it to another level is the places it ends up going, cruelly avoiding expected answers and conclusions for something much more ambiguous, strange, and terrifying. It’s been a long time since a story has gotten me to double check my locks and make sure all my curtains are shut tight, but Zashiki Onna is just the kind of manga to birth that flavor of paranoia.

Movie of the Week | Rewrite (dir. Daigo Matsui, 2025)

A highlight for my year, this time loop drama about a girl who has a short-lived high school romance with a time traveling boy takes about a dozen major zags from its well-worn premise — including making said premise an overt homage to Nobuhiko Obayashi’s classic, The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (and like very specifically his film, not just the Tsutsumi novel it adapts). Written by the greatest writer of time loops in history, Makoto Ueda (aka the writer responsible for River, Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes, and Summer Time Machine Blues) Rewrite patiently unwinds into something as expansive as it is delicate, a generous and kind work exploring fiction and memory and the ways we create purpose while effortlessly also providing some heady meta-reflections on itself in the process. Had my heart levitating a little bit the entire time!

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here's a video essay on roger ebert's relationship with anime