Talking games | SaGa 2/The Final Fantasy Legend II

Watch a 30+ year old gameboy game give me an existential crisis LIVE

SaGa 2 is an absurd game. Released in 1990, only a year after its predecessor—a trail-blazing renegade masterpiece of surreal, meta twists on then nascent RPG genre traditions—the sequel offers up a universe cobbled together from scraps and stitched together with scotch tape, one where the quick brushstrokes used to define it are reflected textually: everything is broken and nothing is as it should be.

This isn’t exactly surprising. Auteur of the SaGa series, Akitoshi Kawazu, has always defined his writing with kitchen sink imagination and incredible brevity, his stories feeling like the worldbuilding equivalent of those simulation videos of cars being smashed together at 1000mph. SaGa 11 is a largely traditional medieval fantasy until (in one of my favorite moments in all of games) you find a gun; SaGa Frontier features a multitude of disparate protagonists—a superhero, a secret agent, a graduate from magic school—all planet hopping through a semi-cyberpunk junkyard universe. Anything goes when Kawazu is involved, and all of it conveyed as simply as possible: single lines given the weight of pages, details painted in just enough to drive the player’s imagination wild.

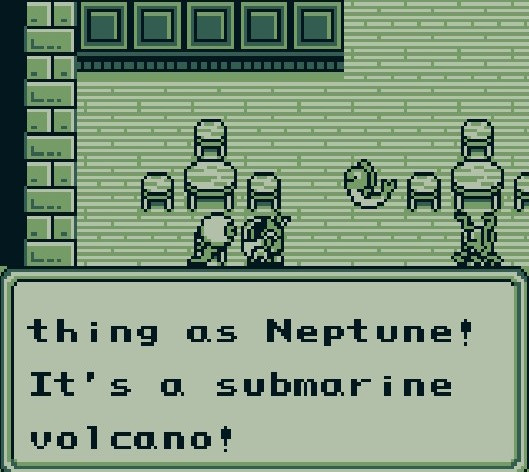

The result of this free-flowing style is something like standing on the edge of chaos, the randomness of the universe both exhilarating and terrifying. It is the same feeling that consumes the characters of SaGa 2—a game of mutants and robots and human-sized giants—who are all struggling for control and stability and power in a place distinctly lacking, trying to tame or explain an absurd existence. Inhabitants of an island fear the vengeful wrath of Neptune only for the player to discover Neptune is nothing more than an underwater volcano; a tyrant king who has made themselves as a god are just a sad little goblin who wished to be free from their own oppression. Time and time again, explanations are invented, systems and power created, and time and time again it all gives way to nonsense.

It’s interesting, then, that SaGa 2 is what it is—a sequel.

The first SaGa is a beautifully ramshackle experience: a sinewy, deformed alien take on the RPG that mechanically feels ready to collapse at any second and encourages the player to break its support beams. Leveling is different for each of its three classes, and none of them involve experience points; powers and abilities come randomly, guided by chance; weapons and attacks have limited uses. It is a game that doesn’t seem to give a single thought toward tradition or what its contemporaries are doing, or how it all Should Be Done.2

But this is not true for its sequel. The same systems are all there—2 remains a very strange title in the greater gaming landscape—but it chooses to refine and iterate on the first and as a result, SaGa 2 is inherently more conservative, defined by the already present framework it must work within. Yes, there is a new class of character added, and sure some of the mechanics have shifted, but playing 2after 1 means that the mystery is gone. There is nothing surprising in the gameplay, no rewiring of the brain. The sense of radical freedom, of anarchic punk experimentation, is gone.

Life has a habit of acting like a sequel—what once was free slowly tightening until it is anything but—and the game itself knowingly wrestles with this.

Within SaGa 2, you follow the player character’s search for their father—an adventurer who abandoned them as a child (jumping out the window like an action hero)—in an effort to understand why this figure of authority, security, and control would leave them. And when they finally do meet him, they discover that they have done to him what everyone else in the game has done: turned something small into something large. Father is a silly, almost pathetic man, just another cog in a greater machine attempting to keep the universe as it always has been.3

A universe, you discover, who’s “true” god is another lie, this time an expansive computer network running deep underground. This world of chaos is programmed and considered. This unending absurdity is designed. In the climax, the player exists the game world to almost literally travel through its code to “fix” it, to maintain things as they were, to avoid falling off the edge. After all, SaGa 2 is a game, it must function; it is a sequel, it must build upon the past.

So where does that all leave us, the player? Is our world just like the one in the game—illusions of invented order and control protecting us from the reality that all this inane meaninglessness is life? Do we all inevitably cling to tradition and the familiar like a scared child clings to a blanket in a thunderstorm? Do we have reason, do we have freedom, do we have a point, or is it all nothing more than a lie? A game?

Who knows. I sure don’t! But I think SaGa 2 has about as good an answer as you could ask. As the game ends, the player’s father sets out on another adventure. Only this time, their mom goes with him. The player does, too.

Together, everyone laughs and jumps out the window.

Music of the week: HikkieP - Eutopia

One of the ultimate vocaloid albums—a furious breakcore barrage that rips and tears and mutilates everyone’s favorite virtual idol, Hatsune Miku, until her voice is nothing but glitched walls of sound. Both explodes the infinite potential of the genre while also feeling like the logical endpoint, exhausting and overwhelming until it does to your brain exactly what it did to Miku.

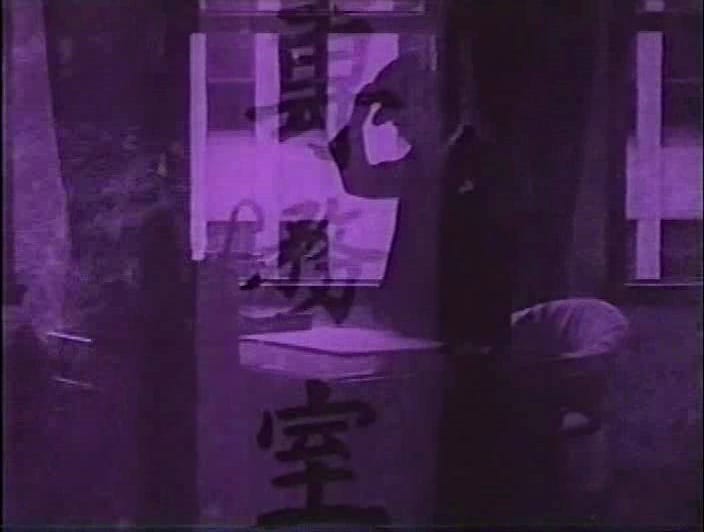

Movie of the week: Eternal Heart

Also known as Undying Pearl, this—the only surviving film of four Hiroshi Shimizu released in 1929—is a stunningly interior silent melodrama of unrequited love. Emiko Yagumo in the leading role absolutely stuns with a performance that perfectly mirrors the film’s texture: everything degrading, layering, overwhelming every other thing until the screen is awash in colored noise. It’s enough to make you really believe she is constantly half a second away from complete mental collapse. There’s a good reason why masters of Japanese cinema like Ozu and Mizuguchi were (jokingly) frustrated with Shimizu’s freakish natural talent, and this is all you need to see to understand why.

oh, and here’s an interview with one of Japan’s greatest living writers (who also makes my brain go funny)

The first three SaGa games were rebranded for English release as The Final Fantasy Legend (booo) ↩

To an extent—we can’t forget that it is a game, it has rules and was programmed and everything that seems chaotic is, in fact, carefully considered. ↩

very Hunter x Hunter, I know. You have to wonder if SaGa was an influence on famed video game enjoyer Togashi. They certainly share a similar style of genre agnostic fantasy. ↩