Talking games | The Portopia Serial Murder Case

Purgatory made digital.

(spoilers for The Portopia Serial Murder Case)

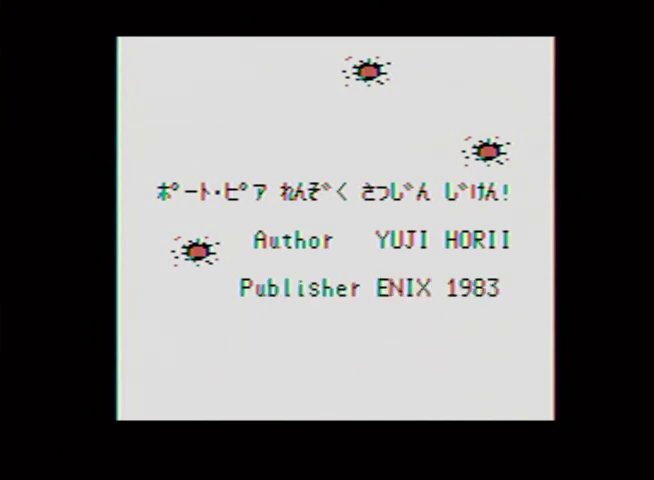

The original cassette for The Portopia Serial Murder Case screams when it starts. Released for the PC-6001 in 1983, the technology wails a high-pitched screech as if in pain when loading, and when it does, all you are greeted with are bullets through the monitor, the title screen a violent declaration of style and intent. From second one, before you even press a thing, Portopia announces itself: This is not a happy story. Murder never is.

After the cassette screams and bullets fly, the world of Portopia—our world, the game set in the real city of Kobe—is slowly sketched in line by line. The player has nothing to do but watch this mystery of murder and crime be methodically created bit by bit. It’s quiet, it’s slow, the cold mathematics of programs and lines laid bare.

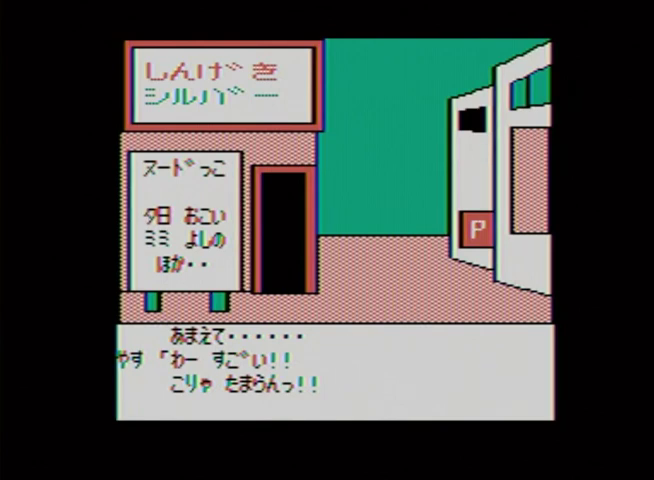

pc-6001 screenshots taken from 星野林檎 on youtube (bless up)

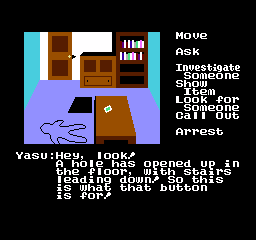

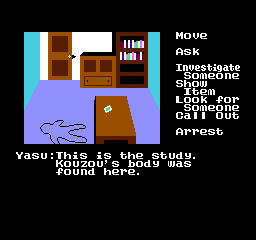

And when the game finally starts proper, the victim’s body is already gone. Kouzou Yamakawa, the hardened ruler of a large loan company found dead and locked up in his home by his young assistant, Fumie, has been taken away, cut open to peek inside. The most anyone will ever see of him anymore is the white chalk outline where his corpse used to be. Like all mysteries, Portopia’s is one defined by what isn’t there, the crime scene like the hollowed room of a ghost.

The outline of a city, the outline of a corpse. At every moment, at every turn, a growing absence.

That absence is what defines Portopia. It seeps deep into everything, staining the entire world. There’s no music and very little in the way of sound effects, instead filled with a pointed silence. There aren’t any people either, only suspects you call when you need them. Only them, and the corpses.

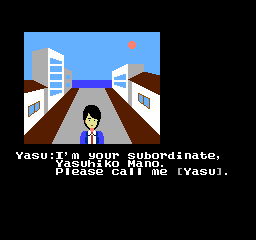

Well, and Yasu.

With the player taking the role of a detective investigating Kouzou’s mysterious, seemingly impossible murder, Yasu acts as your assistant, a young hotshot eager to please and easily given to emotion, and it is through him that the entire game is filtered. You, the player, are never shown or given a name. You (arguably, depending on how you interpret inputs) never speak. Instead, you give commands to Yasu who in turn carries them out, putting the game in a strange, distanced space where you are interacting with the world through Yasu but not seeing it through his eyes.

This is accomplished through a text-parser system. Similar to how text adventures (or interactive fiction) work, the player types in what they want to do, and, assuming the words used are understood, the game does it. In this case, that comes exclusively in the form of commands to Yasu. “Go here. Talks to this person. Examine this.” You feel a step removed from the game world, but this command style of typing also forms an intensely intimate superior/subordinate relationship between player and Yasu. You are the one in control. You are the boss, the god, the star of your own procedural. You have no power at all.

When I say procedural by the way, I mean it at the genre’s most extreme. Portopia is a purgatorial stasis of mundane investigation, looping the same places, the same faces, and the same questions over and over again, looking for clues that we all know aren’t even there. There are several moments that seem impossible to arrive at the solution of without outside help, either because of single pixel sized details or labyrinthine requirements to get a new answer from the same well-worn prompt. It’s games as a cul-de-sac of dead-end circles, taunting player with mounting frustration, almost the only realistic way through being to physically spreadsheet out every dialogue option chosen and when. It’s enough to drive anyone mad. It can feel like no matter what you do, everything remains the same. To put another way: Portopia feels like a ghost world, and you are incorporeal.

This dull repetition and floundering for answers can lead in a few directions for the player. Maybe it’ll make you angry, maybe you’ll start acting out of a disconnected curiosity. Maybe it’s just because you think it’ll be fun. But however it happens, it inevitably does. At some point in the game, you will assault a witness. You’ll slap them, punch them, beat them half to death by just typing a single world, pressing a single button. It’s fine, it isn’t you doing it, it’s Yasu. Besides, they aren’t cooperating. You just want answers. You just want to finish the game.

And it works.

There’s a lot to be said for games with options and choices, different ways to solve the same problem, but there’s just as much to be said for games that don’t. Horii famously plays with this illusion constantly throughout his career, the Dragon Quest series filled with dialogue choices that just loop back on themselves or are refused outright. In the case of Portopia, its cruel decision to force the player to commit police brutality is, I think, one of its most incredible moments. It strips the player’s morality away in an aggressive act, demanding you be made complicit.

Yasu, for his part, seems desperate to be done with the whole affair. There are several point throughout the game where he tells you to stop. We’ve already found the killer, he says, we know who it is. They’re already dead, or they’re here, ready to be arrested. The nightmare is over, you can finally leave purgatory. End the case. Turn off the game. Of course, things obviously aren’t finished. This is just a rookie partner making rookie mistakes, hungry to move on with their life. But doesn’t it sound so tempting? To be done, to leave it, to be satisfied with the answers you already have? To go back to the real world where you definitely aren’t trapped and complicit and drowning?

So you continue to dig, slowly and methodically exhausting every possibility (once again, the lines drawing in the game come to mind), inching closer and closer towards the truth. But maybe you should’ve listened and quit, because when you do discover the killer, it isn’t an answer you want.

It’s Yasu. Your partner, your friend, the one who does everything you tell them to do, who you experience the entire game through. Even if you can sus him out early, or suspect Yasu thanks to the traditions of mystery fiction, the decision to make him the killer is a deeply clever in that it directly challenges the player’s relationship with a game. You, the player, are not the killer. You don’t literally experience Portopia through Yasu’s eyes. And yet…aren’t you? Don’t you? Where exactly is the separation between you, your player character, and Yasu? Is there even one at all? It warned you in the beginning with gunshots and screams. This isn’t a happy story. The credits roll, police sirens blare.

And then it happens again.

The same place, the same corpse, the same impossibilities. Kouzou Yamakawa locked away all alone with a knife in his back.

The Portopia Serial Murder Case for the Famicom (NES) is a completely different beast than its personal computer counterpart, despite what initial impressions might have you believe. Released two years after the title first hit the scene, the story hasn’t changed. The same crime occurs again and Kouzou’s ghostly outline returns to its impossible little room, the player sent out with the killer Yasu to investigate a purgatorial Japan once more. Despite the changed form, it all loops on itself once again, beats playing out in ways that you’ve come to expect. Until, that is, the end. Because it’s as the mystery reaches its climax that you realize the world has changed.

There’s a hole next to where a corpse should be.

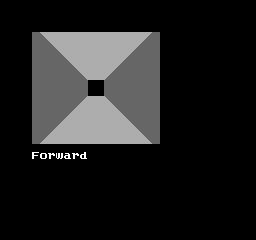

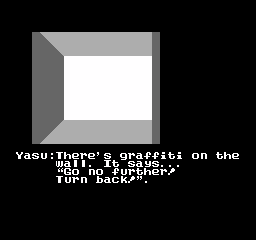

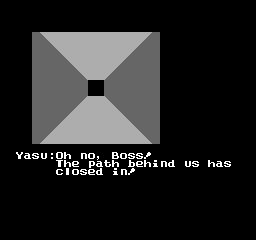

The underground maze of Portopia is one of the most shocking sequences in game history. Hidden below Kouzou’s home, the entrance right beside where he died, it is a genuinely destabilizing discovery—a sudden nightmare shift in genre, control, and perspective. For the first, and only, time in the game, the player takes direct control. There aren’t any orders being barked, no layer of separation between character. You press forward, they walk forward; press left, they turn left. And while the harsh white and blacks—the maze is notably devoid of color--call to my mind the similarly searing nihilism of a director like Akio Jissoji, tonally, it’s perhaps closest to something you might find in a Kiyoshi Kurosawa horror film—the slow-build silent, unknowable, vaguely unreal repressed dread of Cure or Pulse. This is a place that shouldn’t exist, that makes no sense geographically, that would be impossible to create in the real world and which feels ripped out of an entirely different game.

Pathways down here open and close, granting new directions and cutting off old ones, as if the walls themselves were alive. And they might well be. Hiding the true intentions of the killer, wandering the maze is like wandering into the unconscious of Yasu, narrative stripped away for pure emotional expression of a broken, hollowed man. Graffiti scrawled on the walls that mostly act as real-world references and jokes are primarily fun, yeah, but also help in creating a sense that you have descended below the game itself, that you are somehow beyond the code you were meant to see. It’s here, in this silent world without color and beyond reality, that you find Kouzou’s diary and learn the truth and the tragedy of The Portopia Serial Murders.

Kouzou, ruthless, cruel, acting out exactly what his job in finance demanded, drove Yasu’s parents to suicide. Money can do that so very easily and it tore Kouzou up inside. Out of unbearable guilt, he hired Yasu’s sister, Fumie—the one who found his body—to be his secretary knowing full well who she was and how much she wanted him dead. It didn’t matter, he figured. Maybe it was even for the best that way. He set up an inheritance for her, all the money in the world waiting to gifted to her one day. He believed she deserved to be happy, a happiness that could only fully materialize with his death.

And then Yasu killed him.

The murder of Portopia is a prison for everyone involved. It’s a labyrinth the cast can’t escape. Just as the game itself tightens its grip on the player, traps them in endless circles of moral decay and let’s them rot, so too does the house of the murder capture Yasu. He can’t ever leave. It’s taken him, stolen him, killed him. It’s all he is. And then it all happens again.

Again and again. Again and again.

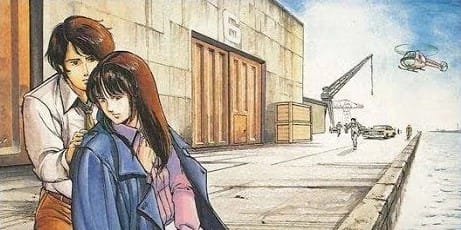

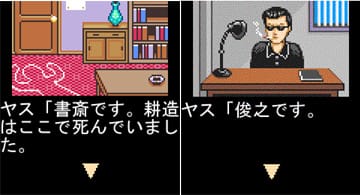

The Portopia Serial Murder Case has been rereleased and remade several times since its arrival on console, namely in the form of mobile versions during the early 2000s, giving the game sleek, detailed illustrations that up the sense of liveliness of the city and its people. It’s a fundamental shift in tone, creating something more gritty than hollow, but it’s a welcome change, allowing the game to continue to explore itself in different ways, mining new meaning and revealing new sides through the visual shift.

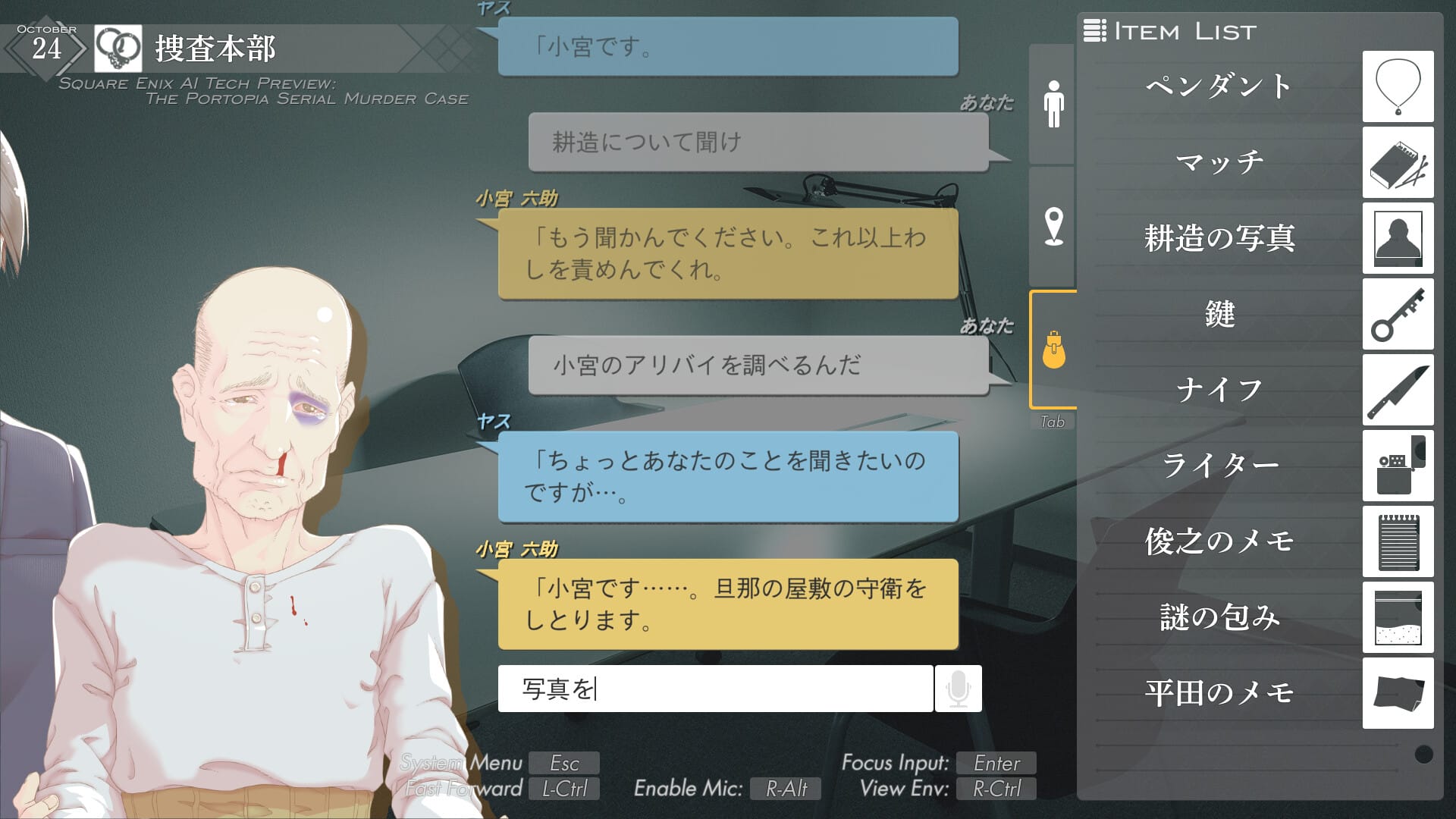

Most recently, in 2023 Square-Enix used the title for an experiment in text-based Generative AI. Here, for the first time in forty years, the game returned to its origins of PCs and text-parsing.

It’s a disaster. A complete failing not only of its misguided attempt to show the possibilities of modern huckster special, AI, in a game, but as an adaptation of one of the most important games there is, it all but completely breaks under half-hearted techbro ideas, tone, pace, and style ripped away for endless, meaningless frustration. Received horrendously from all sides—even as a free game—it comes across like a Weekend at Bernie’s style playing with a corpse, a wildly disrespectful act that implies the company in charge of Portopia well and truly does not care about one of the most foundational games ever made. It feels like they don’t mind if it dies, and they’re happy to be the ones to kill it.

But stories don’t work like that and art doesn’t work like that and lives don’t either, not really, because this isn’t the end. This crime has happened before and it will happen again. It’s only a matter of time. We’ll see Kouzou’s body again and we’ll poke and we’ll prod and wonder. We’ll discover the killer who is both us and who isn’t, commit acts we wish we could take back but never can, mire ourselves in awful complicity born from a false sense of distance. And maybe one day the mystery will be well and truly solved and we’ll finally understand.

I wouldn’t count on it.

(info on Horii and the development of Portopia taken from this interview)

Music of the Week | Togawa Kaidan by Hijokaidan x Jun Togawa

My favorite harsh noise act teams up with my favorite avant-pop freak-idol Jun Togawa to add a nice layer of absolute ear-splitting chaos to some of Togawa’s most beloved tracks. I think of Hijokaidan’s many collaboration works as good introductions to harsh noise, easing you into one of the most extreme (both in terms of sound and experimentalism) genres with graspable melodies and structure fading in and out of the static, and there’s no pop artist in the history of earth who can fit right in there better. When Togawa screams “Say ‘I love you’, or I’ll fkn kill you” and the guitar amps explode…I feel that.

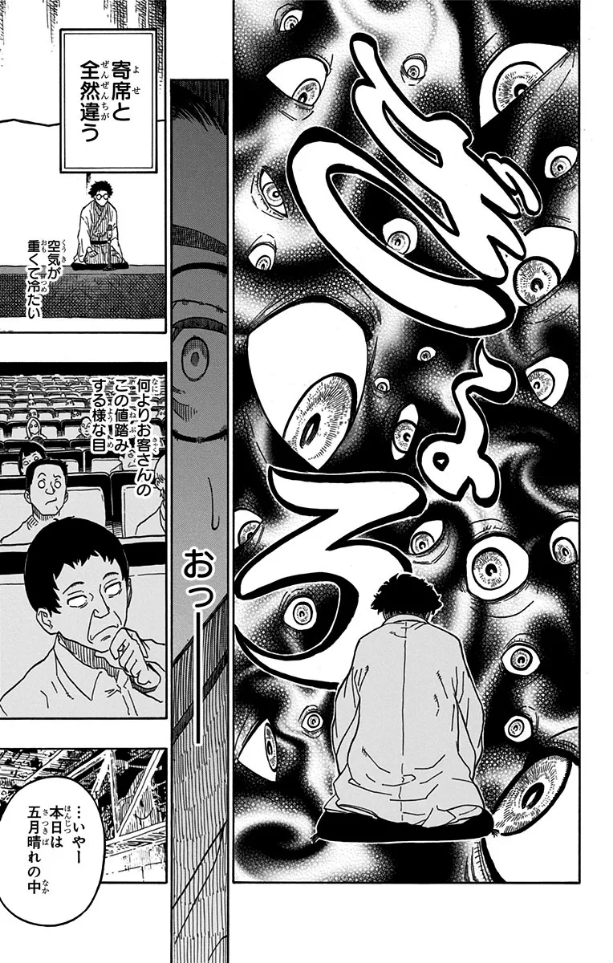

Book of the Week | Akane-banashi by Yuki Suenaga and Takamasa Moue

One of the highlights of the current Shounen Jump lineup following a gyaru girl on her journey through the world of rakugo—this old style of one person (usually comedic) live storytelling. Akane-banashi exists in a state between present, past, and fiction, all swirling up as long flashbacks reoccur and decades of inherited emotion are expressed and evolved through the telling of stories that have been told so much they are etched in the soul. Of course, this is still a Jump series, which means it’s all that AND a non-stop roller-coaster of rivals and stakes and hot blooded passion, often taken the shape of sports manga to tell its beautiful tale.

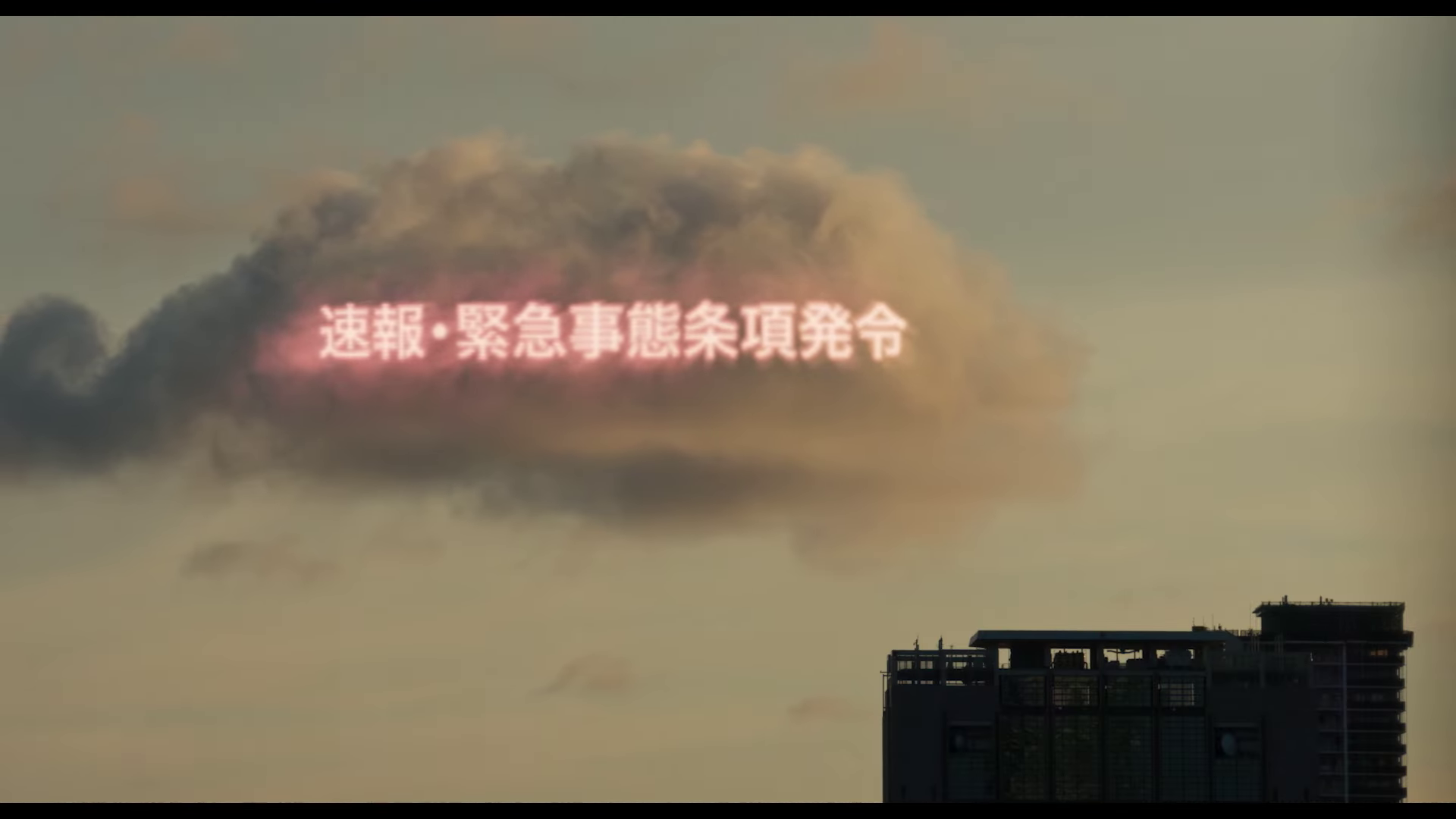

Movie of the Week | Happyend (dir. Neo Sora, 2024)

Teen drama that actualizes the politics of anxiety and discontent that quietly lurks in every story of the genre. Heavy shades of Shinji Somai linger as a group of high-schoolers clash against the everyday authority of principals and parents and quiet oppression as the country collapses into undisguised fascist authoritarianism in the background, a vague threat of a cataclysmic event hanging as the frequency of earthquakes increase. Really wonderfully considered stuff that played like absolute gangbusters for me.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh and friend of the blog Jai made an unreal video essay on one of the best manga ever, Pink