Talking games | Towelket 2

On the experience of being haunted by a game.

full spoilers for Towelket 2

content warning: discussion of sexual violence

Here's an old one from the Baxter archives because I've been under the weather lately and unable to keep much writing done. This bad boy was actually originally a video--one of the first bits of writing I put on the internet!--which you can watch here if the roughly 8000 copyright claims will let you.

I’m being haunted by a video game. It’s a term used a lot when discussing art — haunting. But as silly as it might be, I really do think there is something to the idea. It happens a lot after all, and I think to most people, where a work of art, whatever medium it might be, finds itself invading your life. It might just be a moment or an image, or nothing more than a single word; but whatever it is, it lodges itself into your subconscious and never lets go. Like a ghost hanging onto your back, it weighs on you. It whispers to you, and you don’t always recognize it’s voice for what it is. You confuse it, you find fragments and images of it elsewhere, in other works, in the day to day moments of your life; you see it just as you see a ghost when you wake up and gaze at the shadowed outline of a coat. And I’ve started thinking that maybe the best way to exorcise one of these ghosts, to free myself, is to talk about them, to share it with others. To propagate a haunting, as if it were a disease.

So, let’s talk about it. Let’s talk about Towelket 2.

Towelket: One more Time is a series of games made in the RPG Maker 2000 engine by a single Japanese woman who goes by the name Kanao. RPG Maker is a hidden world of gaming unto itself, and there’s a seemingly infinite amount of fascinating, experimental, and ambitious games made with it by various indie creators, especially in Japan. Occasionally some of them make waves worldwide — Yume Nikki, Ib, Corpse Party — but most of this underground history of independent Japanese game development remains unknown and largely inaccessible to the western world due to, understandably, the language barrier and the innately niche nature of the sub-culture.

It’s expected, but also a shame. Independent game development like the work done in RPG Maker represents something beautiful in the medium; freed from the shackles of publishers, profit and capital (most of these games being released for free), as well as an allowance for those unskilled in coding or art or design, creators using RPG Maker are able to explore and experiment freely, frequently taking the skeleton of the traditional JRPG and molding it into something wholly unique. Here, games become startlingly personal, expressions of ideas and passions and beliefs unobscured. There is a deep honesty and truth that lies here among the rough, the amateur and the broken.

hich brings us back to Towelket. A series of separate stories related only via reused character models and names, and occasional references. It is as if Kanao has a cast of characters, of personal actors, with which she can explore her thoughts.

Towelket 2 specifically, on its face presents as a light, quirky, comedic game. It is set in an absurd world very much unlike our own, one where the main character Mocchi is in love with a cow, where almost anything in the world can be picked up and used as a weapon — from sticks to chairs to vending machines — and where Mocchi’s childhood friend Paripariume (the names too, as you can tell, reinforce just how silly it all is) joins you in fighting enemies as dangerous as rats and frogs. And story does not disappoint on this front, beginning it’s crazy plot with Mocchi’s cow love interest being abducted by duck looking aliens who, not long after, use said cow as bait on a fishing line to kidnap Mocchi as well.

The plot is silly, yes, but there is a noticeable melancholy to it not unlike that of the series the game clearly draws inspiration from: Mother. Here too are games that are modern and fun but which have a certain air of sadness that hovers delicately above. Just as the Mother games tackle ideas of capitalism and family with humor and kindness, Towelket 2 deals with loss. It examines and looks into the pain of losing somebody, of grieving, of suddenly only having memories.

And it approaches this in a beautiful way. At any point in the game, you are able to enter into your own mind. Here there sits an empty garden and a home. As you progress through the game you earn seeds which you then plant, turning that garden of your mind from a barren patch of land to a beautiful array of reds and yellows and blues, each flower you grow in turn increasing your stats. Likewise the once empty home becomes increasingly populated with things and people as you move through the story, doors unlocking and revealing more of this place which houses your memories. And all of these things literally make you grow — your stats increase, you learn new techniques, gain new skills. It is calm and peaceful here, a wonderful metaphor for memory, one that takes advantage of the unique capabilities of games. Moments of joy and moments of pain leave memories all the same here. They are a part of you whether you want them to be or not, and it is through these memories, these experiences that you are you. You develop. You become stronger thanks to them. It suggests that perhaps there is beauty and meaning in remembering, even in the face of loss, even when remembrance is painful. That in some way, it is memories that make life worth living.

So, taking control of Paripariume, who is in love with the now missing Mocchi, you leave your little town for the wider world, for the city, to find the person who matters most to you, to finally experience life. To fill up your house.

But as Paripariume arrives in the city and begins her journey, we return to Mocchi, waking up in an alien spaceship that seems almost organically made — a heightened parallel to what Paripariume experiences as she explores a strange, dense world of people. It is as if these physical spaces are alive, much like the ever evolving structures in your mind.

There is a sense of unease as you progress deeper and deeper into the ship, fighting off aliens who see you as little more than a curiosity while Paripariume wanders deeper into the city as the sun begins to set. And then it happens.

Mocchi is shot dead.

Disoriented, the game returns to Paripairume, lost in a city at night. Alone, confused, young. A man, none of these things. A dreadful, unbearable fade to black.

It becomes all too clear: this absurd and silly world isn’t as removed, as kind, as it seems. It is, in fact, an awful reflection of our own. And Towelket, this cute and charming little game made by a single woman living in a patriarchal, conservative world, is a scream into the dark. It is a ghost, and it intends to haunt us all.

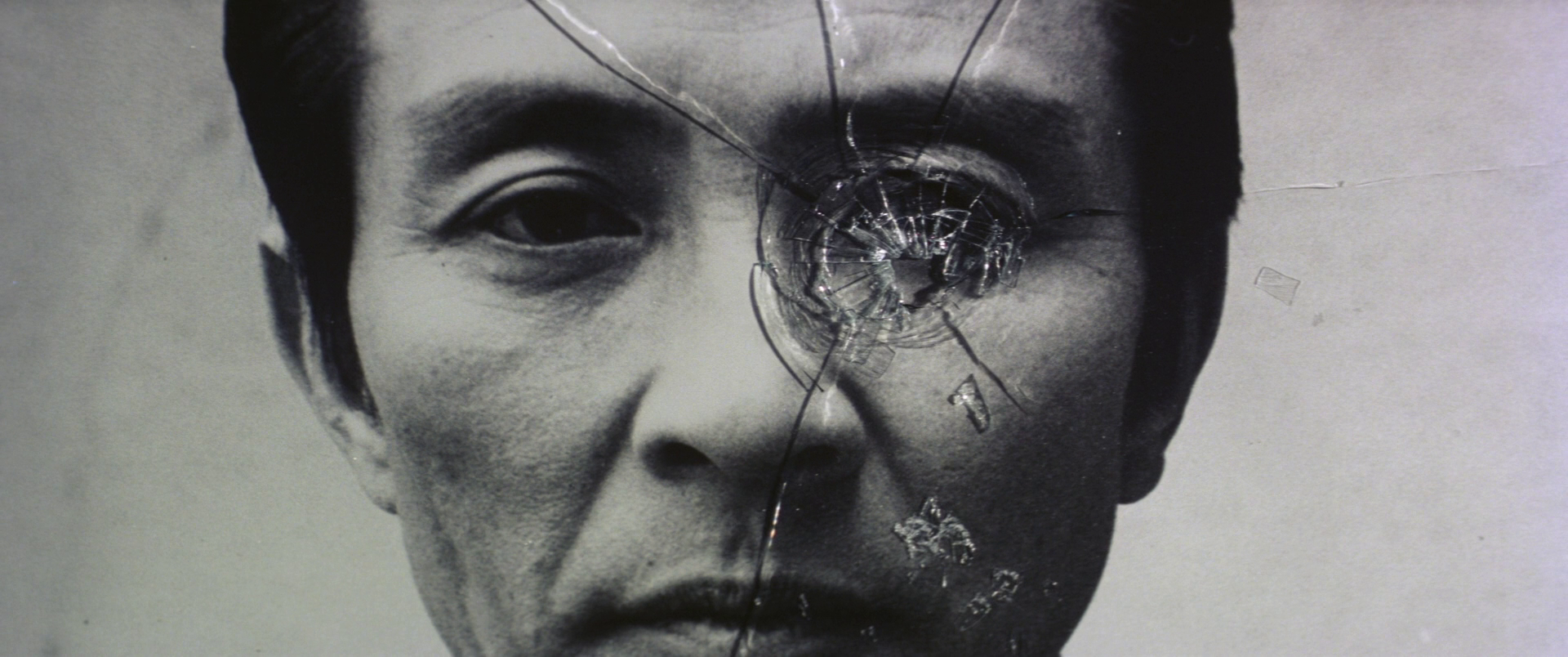

It is not a coincidence that most ghosts in Japanese fiction are women. The Ghost of Yotsuya, Hausu, Don’t Look Up, Ugetsu, Botan Doro, Bancho Sarayashiki, Ju-on, The Ring; it is not an accident that these stories, one after another, finds that the one who is betrayed, attacked, and murdered is a woman. Ghosts are, after all, spirits who cannot move on. They are manifestations of those who have been, in some way or another, abused by power. And, living in a world wrapped up in patriarchal systems, it is all but impossible for a woman to not experience this violence constantly. Even if there is not a singular figure carrying out this abuse, that which creates a ghost exists on a systematic, societal level. We exist in a world that attempts to deny women equal pay, that questions their intelligence and emotional stability at every turn, that physically demeans them and tries to take away their right to their own bodies, to consent. The entire world, all of us, are the deserving target of vengeance.

You will notice this in the trends of modern Japanese horror, which pushes ghosts away from the personal and onto a more explicitly societal level. In The Ring, Sadako can’t be “solved,” she can’t be placated or put to rest. She is all consuming, and the only way to save yourself from her is to spread her to others, because we are all implicated in her death, we are all, in some way, part of the system that permitted her suffering. And many films such as The Ring go further to suggest that the very act of watching their movies, of engaging in the stories they belong to, is in some way an act against them in itself. There is a question of the objectification and fetishization of women and their suffering here. The ghosts emerge from our media, possess the digital, haunt our entertainment. Art here has literally become haunted. And the ghosts therein have become apocalyptic forces with no end, their anger and sadness and pain hungry to consume the planet.

When you gain control of Paripariume again, several years have passed. She has been forced into sex work. Unrecognizable from the child she was before, she no longer shows the same excitement she once did, the verve for life, the warm optimistic glow. However strong she might have been, it has been systematically broken, stripped from her. As you discover during battle, she has been literally forced back to level one. The only thing, it seems, keeping her going, is that house — her memories of a younger self, and of a boy she loved so much. She has become trapped and oppressed in the system, working exactly as it was meant to.

And this oppression casts its net wide, every character joining your party in some way being victims of the same systems of power which allowed a young child to be taken and abused. It is, again, not insignificant that, saving Mocchi, everyone in your party is a woman.

Besides Paripariume, you also have Ketsuage, a lonely scientist living with her own robotic creations, as if creating her own children, her own structure of control; and Mitsue, a successful TV announcer regularly belittled and demeaned by her male bosses, culminating in her being fired for being too old, not cute enough anymore. To the faceless heads of this company, she is nothing more than a commodity, an aesthetic object to enjoy looking at.

And when looking to the world of entertainment, you find a countless number of Mitsues. You see women forced to apologize, made to act subservient; see them endure humiliation in front of millions, expected to do nothing but shrug it all off. You see actresses denied opportunities after reaching a certain age, the industry deciding that a lead can only be young and traditionally beautiful. And you see those who are only given a single choice: throw away their career, their dreams and their livelihood, or be assaulted. Be taken advantage of by those in power who see nothing but an object of their own pleasure. It is like a microcosm of the conservative society it belongs to.

Mitsue responds to her firing, filled with hatred towards the world, by attempting suicide. Her life, which she had defined up until this point by expectations and desires defined by men in power, has no clear purpose without the advantage of youth. She sees no escape, no reason for continuing. So, when she meets Mocchi and Cow after her failed attempt, she can only laugh. An alien invasion. A boy married to a talking cow. A world where she isn’t even allowed to choose when she dies. It’s all so silly. It’s all so absurd.

And yet it is also real; the truth. The world makes no sense, not really. Cow and Mocchi are both, in actuality, clones, just another part of a long line of copies of the originals who were taken by the aliens so many years ago. It is clear, and becomes clearer later when we discover that the aliens can ‘flip’ Cow at any time and essentially take over her brain, that their emotions and their memories do not entirely belong to them. Indeed, Mocchi has no memories. He is a blank slate — a true silent protagonist. Exactly what the aliens want — somebody empty, somebody who won’t question the way they shape the world. Somebody who can be, according to them, a perfect vassel with which to spread themselves.

Cow on the other hand is full of memories, fed images of happiness and peace. She is spending her life with the man she loves and their children. She is wholly supportive and helping of Mocchi despite his lack of love for her — despite the fact that he doesn’t share her memories. She occupies in many ways, I think, the roles of a traditional housewife as viewed from a masculine angle, as someone who society has conditioned to tie their value and purpose into a male partner. She exists for Mocchi, someone who, knowingly or not, is a creation of a conservative patriarchy.

Which the aliens here clearly act as a literal representation of. They emerge as the characters age, paralleling their growth and realization of the world they live in. Our world. Men are forced to work under them in ‘human processing plants’, slaughter houses for the women they don’t need anymore. You learn late into the game that the aliens are a parasitic lifeform, that they reproduce by invading a host’s body and destroying it. They bury themselves deep into a person’s head and, inevitably, kill and replace them. It is all just like the toxic ideas of masculinity and patriarchy which is insidiously ingrained into our minds, which even who men help support it are victims of.

As the game barrels towards its conclusion, you enter one of those processing plants, and Mitsue, the once TV announcer given in to the absurdity of life, is infected by the aliens and turns. You are given no choice but to kill her, a woman who survived past her own attempted death, who was able to recognize the absurd horror and awful truth of the world. It is only now, when the system permits it, when the only option is of violence against her, that she is allowed to die.

The switch on Cow is then flipped, and she too turns. Just like Mitsue, she has no choice, no free will. All of her actions until this point were simply permitted. Denied her own body and mind she kills Ketsuago and lets out a moo, suddenly indistinguishable from the thousands of other cows, from the clones of herself that she is a part of.

So, in what seems like the blink of an eye, there are only two left. Mocchi’s body begins to fall apart, his arms and legs and eyes dripping, decaying. The clones, it turns out, have a time limit. They have an expiration date and he is approaching it. There is no stopping the inevitable. He will die soon.

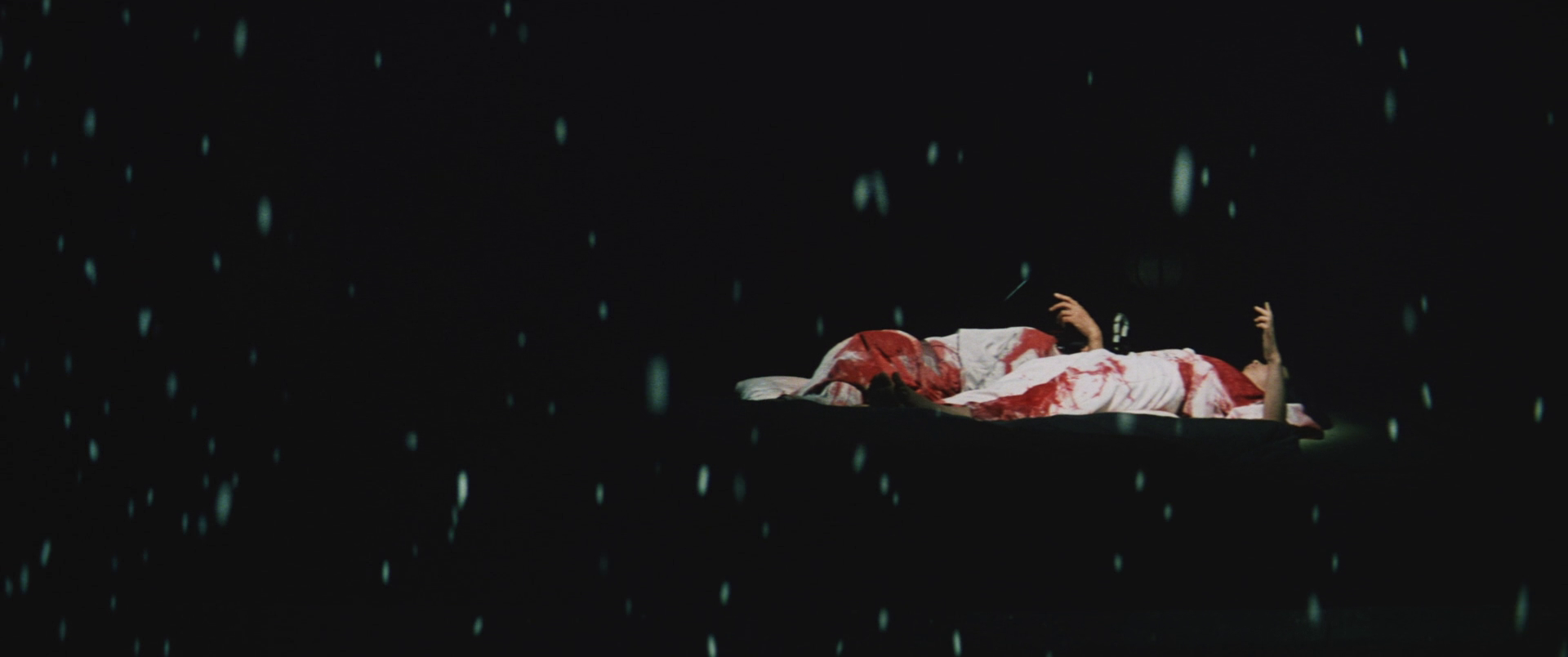

And Paripariume, the kind child, the forgotten one, is taken by a scientist and offered as food for his daughter who has been infected and distorted by the alien offspring. It is not an outward act of hate. But the scientist is a man. He has the power and ability to keep his daughter alive even though she has been consumed by the world, even though she is suffering, and even though it means he will destroy other women in the process. When you arrive there with Mocchi, the rest of your party all dead, his body melting and in pieces, you see Paripariume on the floor, bloody and disfigured. It is too late. Just like Mocchi, she is dying. Never speaking, Mocchi takes her head in his arms. Outside, you can hear clones of Cow being dropped onto the factory like bombs, as if the world is being literally destroyed. There is no escape. There is no chance for a happy ending anymore. Perhaps there never was.

And so, facing the end and a world that never really gave you a chance to win, you return to the place that really matters — the home inside your mind. Your memories. Except this time there is a new door, one that wasn’t there before. One that is dark and bloody.

When you walk inside it, Mocchi wakes up. He is in his bed in his home and Paripariume is standing beside him. She looks as she did all those years ago. As if it were all nothing but a bad dream. A warning that the world is dangerous and cruel, but you can avoid it. Stop it. Keep the wonderful kindness and quirkiness and fun of life. It is like so many stories of moral redemption — It’s a Wonderful Life, A Christmas Carol — but broadened out to a much wider scale. A thematically touching way to conclude a nightmare — a glimmer of hope, a refusal to be beaten by a misogynistic world, even when its victory seems inevitable.

But then you leave your room.

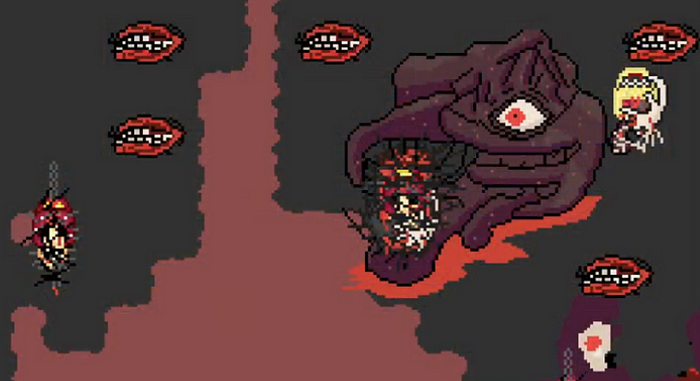

Blood. Violence. Pain. Paripariume tied up in thorns; wandering a fleshy landscape with a face that has been torn off.

The realization: it is her door you walked into. And all of this, this blood and torture and dismemberment, is her in all of her honesty.

This is the truth of the house, of every house. They are haunted. Memories build up who we are. They define us, bits and pieces of interpreted past combining to make an identity. But memories are not always good, and their wounds don’t go away. They remain and fester deep and locked away, buried in a well, under the floorboards, in an unseen attic. The roses in the garden are dyed red from the bodies buried beneath. And these corpses cannot rest.

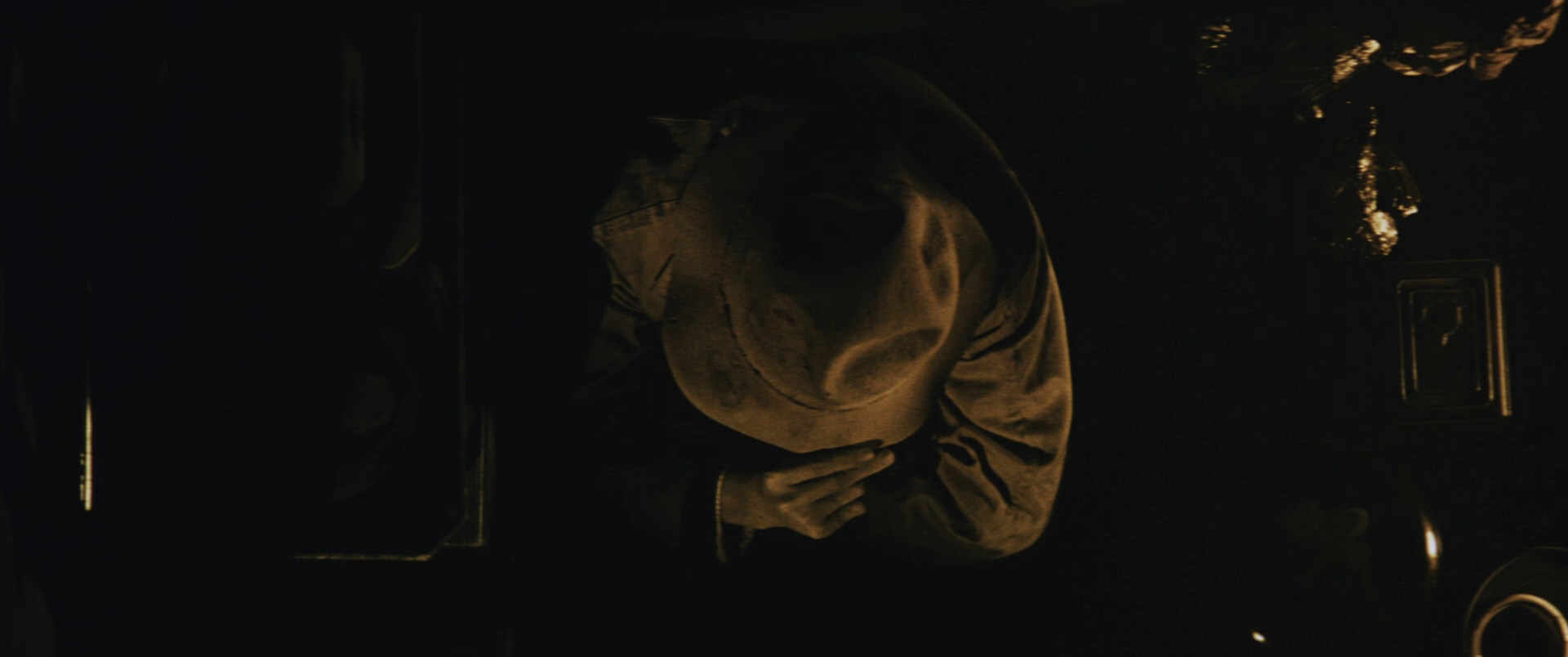

Mocchi and ourselves end up entering into a strange structure of infinite floating halls and hanging doors, the nightmare reinterpretation of what we once saw as a tranquil home always in sight, waiting miles below. This is the true home, a nonsensical and absurd structure. Here we encounter Paripariume over and over again. Here, she finally speaks.

Paripariume has never moved past that night. How could she? How could anyone? Though time has passed and she has left the man who abused her, has found again the person she has dreamed of for so long, has surrounded herself with friends and people who care for her, she is still trapped in that room. She is still a scared, confused child who cannot leave this awful house.

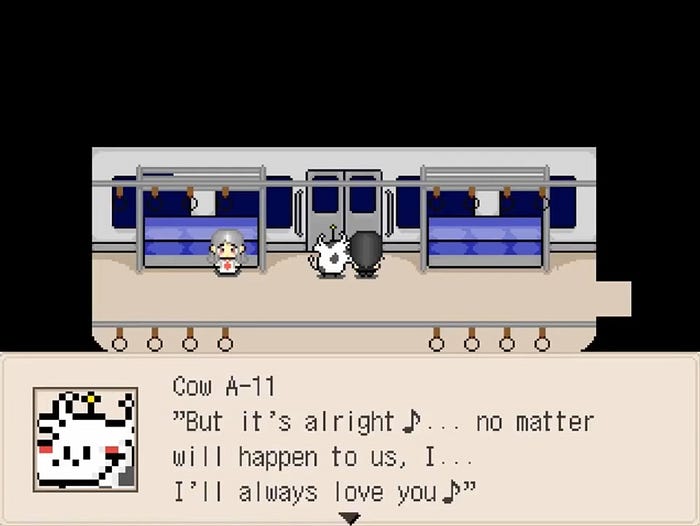

Paripariume, as we travel deeper and deeper, meeting bloody ghosts which follow her, finally confesses the truth. That she is in love with Mocchi. Her memories of him are all she has left, the only ones untainted by the world. And Mocchi, or this empty clone of who was once Mocchi, remembers her, too. It is here in the world of memories, imagination, and shared empathy where, just like the game which they exist in, they are free from the claws of a conservative, capitalist patriarchy. They are able to remember and express themselves honestly without a toxic, parasitic influence invading their thoughts, or giving in to demands of a world that wants them to be nothing more than a ghost. They are in a way like Kanao, quietly making a game called Towelket, with no intention of selling it, nobody telling her what to do, and no influence of how it should all be.

Finally, we return. The world looks the same as it did before; Mocchi cradling a bloody Paripariume’s head in his hands. There is no sound. No dialogue. No music. Only silence as their bodies remain intertwined and still, at last, in a world determined to destroy them, to control and oppress and defeat them, having found each other as ghosts, as pained memories seared onto the geography of the world.

And so I’m finished. I have said all I have to say, thought all my thoughts. If this was intended to be an exorcism, then it failed. But maybe that’s for the best. After all, we as a people are like a child wrapped up in a small towelket trying to convince ourselves that the ghosts aren’t real. That they aren’t really standing there beside our bed, coming for us. That we aren’t all of us haunted just the same. So maybe I, and all of us, should be swallowed up by these ghosts. Maybe then we could finally find a way to stop making them.

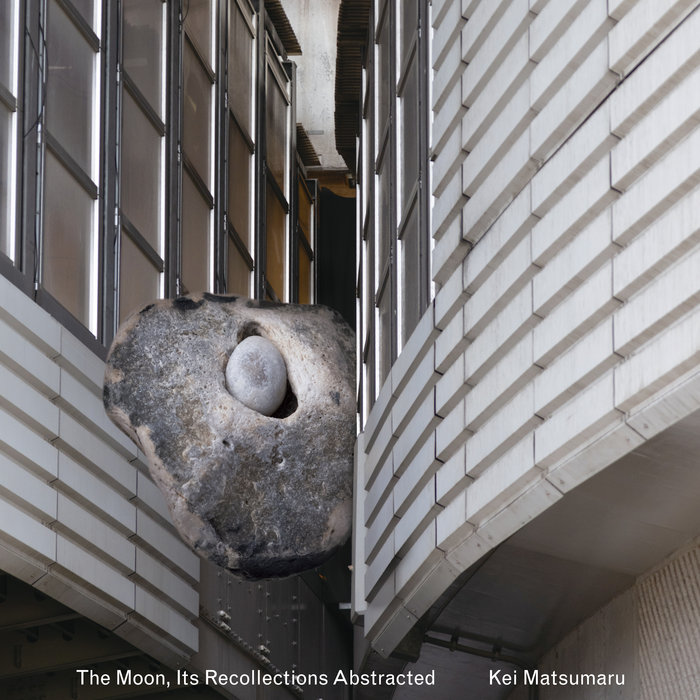

Music of the Week: The Moon, Its Recollections Abstracted by Kei Matsumaru

Kei Matsumaru, who is part of the scene-defining SMTK and frequently collabs with our lord and savior Eiko Ishibashi (she shows up for a couple tracks here) puts out a beautiful, melancholic collection of jazz tracks here. Purposefully made as an interaction between abstraction and concreteness, pieces drift between lonesome compositions and free jazz improvisations, electronics squiggling in from time to time among a stark, spacious, and cold atmosphere. All these adjectives give it away: even at its most frantic, this thing gives the sensation of remembering that there is something missing, knowing that a memory you treasured has been lost. Great stuff perfectly balancing the cold and the heat innate to jazz.

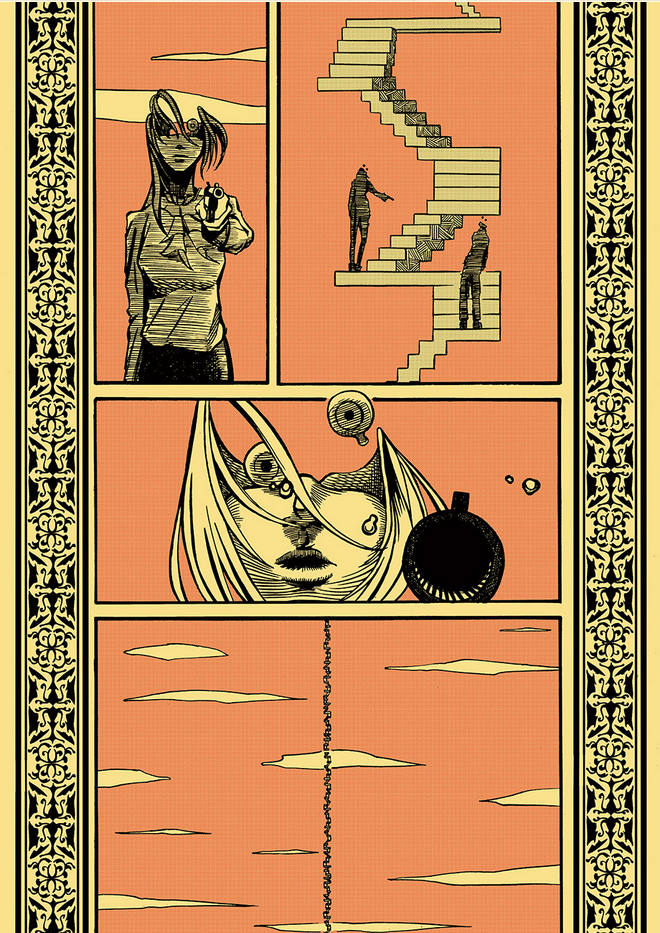

Book of the Week: Hikou Bungaku by Xian Ozn

A beautiful, experimental series of shorts linked only by its focus on two strange high-school girls, Xian Ozn’s webcomic–published by the always fantastic Torch Comics and recently receiving a physical copy in Japan–is impossible to pin down. On the surface it seems like a comedy, but then it frequently lacks punchlines, gag set-ups trailing off into unexpectedly beautiful, meditative moments; other times art and genre take a complete 180 turn, the typically cutesy protagonists suddenly rendered like 70s gekiga protagonists, pop-art models, raw cyperpunk survivors or abstract swirls of human flesh. Completely singular, completely invigorating.

Movie of the Week: Death at an Old Mansion (dir. Yoichi Takabayashi, 1975)

A Kosuke Kindaichi mystery adapted by an avant-garde filmmaker and the legendary Art Theatre Guild production company? You couldn't sell something harder to me if you tried. Death at an Old Mansion is everything you want from Japan's great detective–a clever locked room murder, dense interpersonal relationships, and a politically charged undercurrent–filtered through rigorous filmmaking that is at turns incredibly patient and composed, and ecstatically abstract. Not an easy or fun watch, but one that will pull you deep into its rhythms and feeling.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here's a free (and legal!) translation of an essential book on weirdo manga from the 70s.