Talking manga - Karakuri Circus

Learning how to smile with one of battle shounen manga's great masterpieces

I don’t like my smile much. I could talk about why for days. It’s too wide, for one—the edges of my lips turned thin and small, stretched too tight like someone took scissors to the ends. That my teeth aren’t straight and even like the commercials doesn’t help either, little gap tooth in the middle a sort of awful highlight. It isn’t even just the mouth; sometimes my eyes are too wide or not enough and wrinkles fold weird. It’s a mess. I don’t like it. Pictures are a nightmare.

I remember once being lined up for a class photo in elementary school. Our teacher was behind the camera.

“Say cheese.”

Everyone smiled. I did, too. The teacher didn’t. They walked up with quick, small steps, and pulled me aside. They told me in a harsh whisper to wipe the smirk off my face and smile. I didn’t understand, but I tried again. I must have done it wrong. I must not know how.

Karakuri Circus is a manga about smiling. It’s full of them; facing death and loss and memory and trauma and the worst humanity has to offer, characters grin. They laugh and smile, and by doing so, save others and are saved in return. Not that it’s always easy.

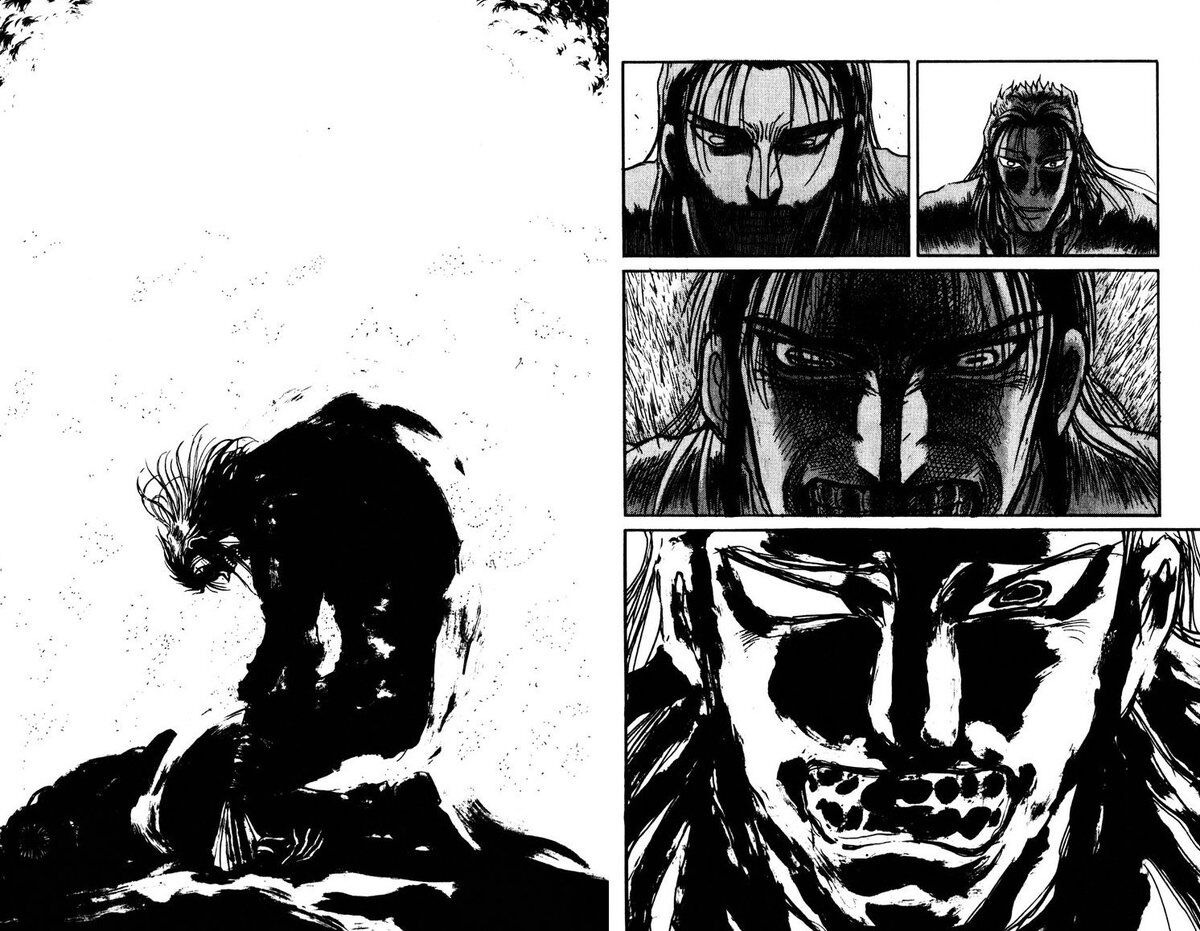

A battle shounen series (think Dragon Ball—those titles that conjure up images of boys with spikey hair screaming and punching each other) about an evil army of automaton robots and the marionette wielding heroes trying to stop them, smiling does not come naturally for any of the protagonists. There is Masaru, a traumatized child whose entire life has been nothing but abuse and loss, turned scared of any action other than running; there is Shirogane, a woman trained to be a tool, guilt and repression convincing her she has no emotions; and there is Narumi, the one who taught them all how to smile who forgot how to himself, increasingly consumed by revenge.

It's all big, operatic emotions, melodrama blown up to its extremes. But then, of course it is. The battle shounen genre has as many possibilities as there are stories written within it, but an overwhelming characteristic is that of emotion made physical, feeling and ideology literalized as flesh and violence. Sometimes the result can be dangerous—empty platitudes, cynical narratives, streaks of misogyny and confused, conservative politics—but it can in equal degrees be a transcendent form of expression and catharsis, fights giving actionable form to the unending push and pull of our own minds. Life might not be filled with fist fights and energy beams, but it sure does feel like it is.

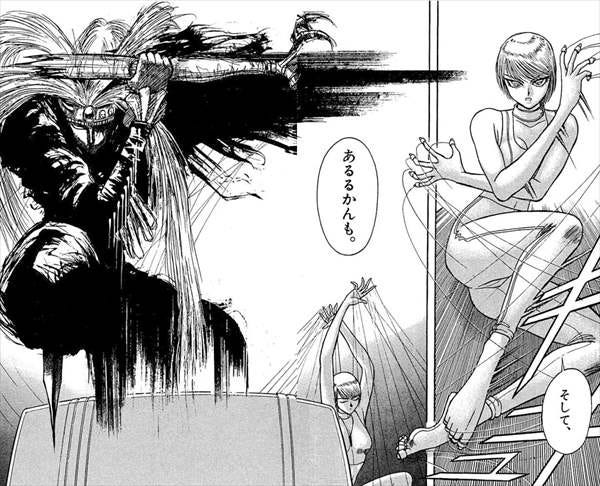

And there certainly are these battles in Karakuri Circus. They are everywhere you look. Time after time the trauma and anxieties of its cast are revealed for the world to see in the shape of villains who aren’t really villains at all but reflections of themselves, haunted by the grand tragedy of the series. Everyone they know and everyone they love seems to die or lose themselves or betray or break, story periodically flashing back to depict a hundred years of circular, unending loss. The more Karakuri Circus expands its scope, the more it contracts—impossible powers, conspiracies, mind-control and literal armies all nothing more than a representation of the complex emotional plays of three sad people. When they fight these horrific creations, these nightmare robot parodies of humans distorted into strange shapes, they are only ever fighting themselves.

Then comes the illness. The Zonapha disease, What begins as quirky character trait—a lack of laughter around someone causing an allergic reaction, their throat closing up—eventually expands to apocalyptic proportions, the entire world infected with a literal life or death need for humor. But how can I laugh if I don’t know how? And how can the world laugh when it knows how even less than me? We are in a world of suffering and tragedy, and it isn’t getting any better any time soon. Forget for a moment, as if it is possible, the war and genocide occurring as we speak—forget all the hatred and racism and sexism and homophobia and transphobia and classism and oppression and the shootings and the stabbings and the murders and violence and hatred and hatred and hatred. Leave all of that behind and the world is still suffering. It is still poor. People are homeless and people are hungry; people get sick, and accidents happen. There’s still nothing to smile about.

We look at our pain and ask: “Can’t anyone help?”

We see billionaires and wonder why they don’t use their money to save the world.

“Don’t be naïve,” they answer while building rockets to mars. “Don’t be a child.” But it’s true. The children are right. When aren’t they?

The main villain of Karakuri Circus makes a rocket, too. His only goes to the moon, but the intention is the same. Why fight the injustices and pains of the world? Why fight what we can mitigate but never truly solve? Why fight ourselves? Escape is better. They watch and read battle shounen—Naruto and One Piece and Chainsaw Man—and all they see is the acquisition of external power. All they see is violence, and they think it good. They crack jokes and they laugh. Their teeth are filled with lies. Are they the only ones who can smile?

Karakuri Circus says no. In the first chapter, facing death in the eyes, Narumi tells the frightened, crying Masaru, “If you need help, shout for help. If you’re angry, speak out. Fight, struggle, do what you can. And if all else fails…I guess all you can do then is smile.”

Smiling, the manga suggests, actual honest-to-God smiling, is an act of resistance, an answer to difficulty, pain, and strife, an acknowledgement and refutation of our universal state of existence. It is not easy, not something to take lightly. The grins those billionaires who control the world’s wealth, who can only ever face artificial adversity they invent for themselves, show the world are nothing more than masks. They’ve forgotten how to really do it.

My teacher was wrong to say what she did. It was cruel, but she was right in one way: I wasn’t smiling then. Not really. It was a lie told for the camera; an imitation and nothing more. It was, like the villains of the story, hollow and untrue.

I don’t like my smile much. But things have started to change. The change is slow—slower than slow, even—but it is happening. Over the years, bit by bit, I’ve begun to show myself kindness, show myself love. I’ve practiced my smile a lot, as embarrassing as it is to admit, and it still doesn’t work half the time. But now when I see it and hate it, I just wince and I laugh and I sing a stupid little song.

“My name is Baxter and I’m a handsome boy~”

Do I believe myself? Will I ever? Maybe, maybe not.

But it sure is better being able to smile.

Music of the Week: Car10 / The Guays - room share EP

Two very likable rock bands share a split ep, each arriving at a palpable sense of adolescence in different ways. For The Guays, this comes in the form of wild abandon, instruments played in messy flury while they all shout and scream pop punk at a hundred miles a minute. For Car10, it’s in a haze of feedback, glimmering guitars, and cracked voices. Either way, the result from the two groups is the same: transporting you back to powerful teenage emotions, celebrating longing, hopes, and lazy passion.

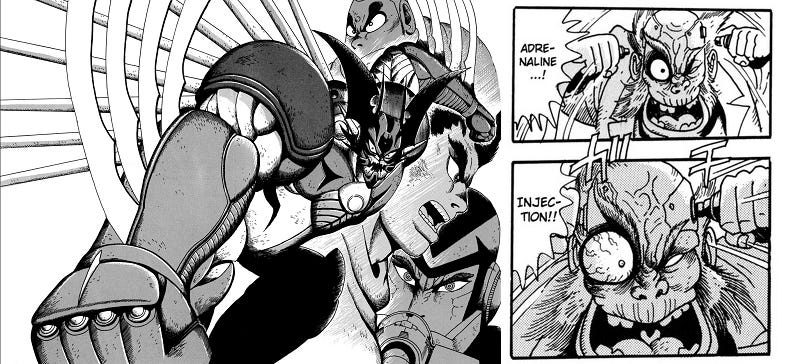

Book of the Week: Getter Robo by Ken Ishikawa

Don’t be fooled by what you think you know about Getter Robo: though it begins as a very fun super robot story often confused as a Go Nagai work thanks to its dedication to the legendary artist’s style, by Getter Robo Go, Ishikawa fully sheds his master’s influence and opens his third eye, reconfiguring the series into an apocalyptic wonder of Absolute Adrenaline. With loose, grimy art that rivals the best in the medium and an eldritch sense of foreboding and escalation that has never been done better, Getter Robo is a mad, gonzo action masterpiece; ambitious, daring, desperate, and completely its own.

Movie of the Week: Escaflowne: The Movie

Takes a now famous fantasy anime series and turns it into a mythic allegory for depression and suicide, where the interior is made exterior, protagonist's emotions literalized into great wars and unexplainable magic and giant consuming flesh armor. Narrative here is just another tool for emotional expression, moving at the matter-of-fact pace of a legend or classic epic, its chaos and confusion (and assault of Proper Nouns) a sort of mirror for a mind in disarray. Gets the deadly seriousness of teenage angst and the sense of not belonging to even yourself with an empathy not many do. But even more important than that? It vibes like crazy.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!