Talking manga | Mojacko

Getting to know Doraemon's weird death obsessed brother.

Everyone loves Doraemon. One of the most iconic characters in anime and manga history, the blue cat robot created by Fujiko F. Fujio is a veritable institution: the star of thousands of episodes of TV, dozens of films, volumes on volumes of manga and books, and the face of merchandise galore, covering any and every product you could possibly imagine. Doraemon is your toothpaste, he is your lunchbox, your blanket, your food and your drink. There is not a single adult or child in Japan who doesn’t know him and his friends (Nobita! Jaian! Shizuka!), his gadgets (Dokodemo Door! Take-copter! Ankipan!), his likes and his dislikes. He has become a permanent fixture, our sustenance and way of life.

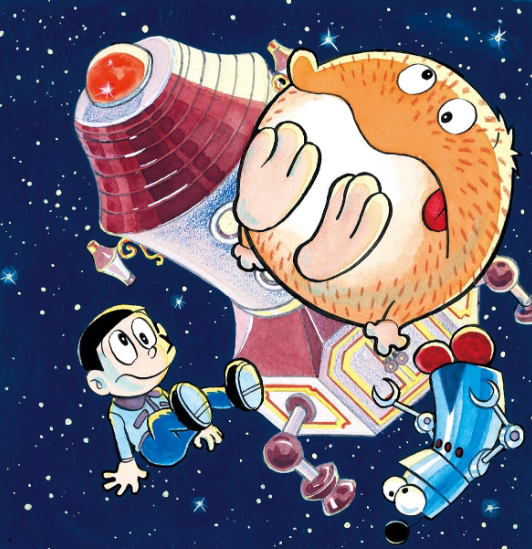

But there is another would-be icon from Fujiko who hides forgotten in the massive shadow of Doraemon; a failed creation abandoned, turned strange and horrible, like a creature society tries to ignore. There is an uncomfortable danger to them, a darkness and desperation. There is Mojacko.

1969 was a big year for Fujiko F. Fujio. Riding the end-tail of the Obake no Q-Taro boom—an explosively popular 1964 manga and anime that all but took over pop culture for several years—the artist found himself in a period of experimentation, testing the waters with various projects and genre and expanding his creative potential. This was the year he was approached to make his first foray into adult manga with the now legendary one-shot The Minotaur’s Plate, beginning a new side of the artist’s career producing dozens of critically acclaimed speculative-fiction shorts, blending his trademark humor with heady ideas, pointed satire, and a welcoming of violence and sex. This was also the year Doraemon was unleashed upon the world, a series that would eventually (though it would take some time) make the monstrous popularity of Obake no Q-Taro look like nothing more than a warm-up, his children manga purified to its purest essence.

Mojacko exists in the in-between of these two sides. It is sci-fi Seinfeld, It's Always Sunny in space; a ballistic comedy adventure about the three worst people you’ll ever know digging increasingly deep holes for themselves and coming out the other side without having learned a single thing. Greedy, lustful, lazy—the entire seven deadly sins represented in three bodies: an unpopular young boy, a neurotic robot, and a horny little alien.1 A found family bound together by desire for adventure--as a method of escape, of feeling, of delusion and dreams--these three losers of life don't so much travel the stars as fall through them, the universe cruelly dishing out karmic retribution at every turn. It’s hilarious and charming and moves at a mile a minute. It is also obsessed with death.

When I was younger, I spent a lot of time imagining my own funeral. I think most people do. Who would show up? Would anyone? What would they say, what would the weather be? How would my body look in the casket? Sometimes I’d let my imagination run earlier: how would I die? Would it be heroic? Would people cry? There was something comforting and exciting in the delusions—though I never actually wanted any of it to happen (I’d much rather live to a healthy 250 years old, thanks), there existed a romantic air around death, the one thing I can never truly know.

Mojacko is the same. Trapped in a strange comic meditation on mortality where existential threats are rendered through pratfalls, chapter after chapter and page after page, the three stooges of this story stumble into increasingly complex, distressing events, death looming closer and closer.

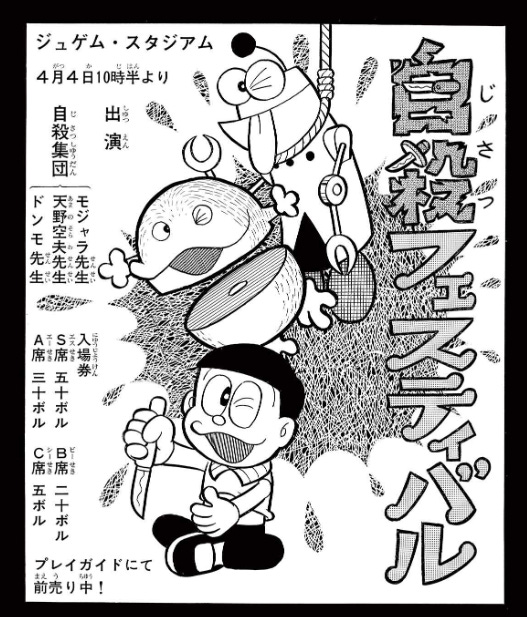

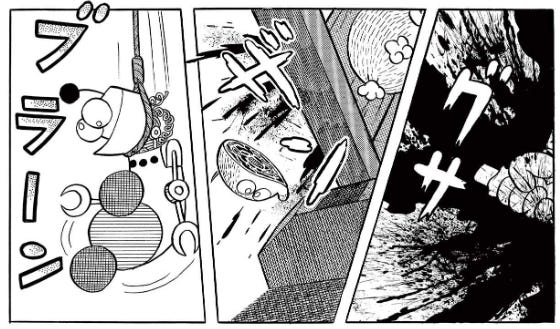

In maybe my favorite chapter, the three emotionally abuse their way into a comfortable life, adopting a scam where they pretend to be violently suicidal so that strangers will take pity and give them free food or money or a place to stay. They weaponize their mortality and all but literally turn death into a toy to play with, delighting in it like how I used to delight in thinking about it—tragedy turned fun pastime. But then they try their scam on a planet of immortal beings, people who have no conception of what it means for a life to end. And suddenly those fanciful daydreams become all too real as the lie spirals to a size that can’t be backed out of, the entire planet brought together for an arena show of their deaths. What were once words become images—the cute pop art character’s imaginations overwhelmed with the image of cutting open their stomach or being decapitated, blood filling the page. And in the stands, the crowds cheer.

Their death becomes nothing but a show, entertainment for a hungry audience that doesn't understand it, for people exactly like them and exactly like us: people who imagine their funerals. None of us know death, not really. None of us ever can. The closest we can ever get is to watch it in others and imagine it in ourselves. And we do, time and time again in story after story as the characters tremble in fear before their own corpse.

I read this chapter and other chapters like it (The Gang Meets The Grim Reaper, The Gang Ends the World, The Gang Casts Away Their Physical Bodies and Embrace Perpetual Pleasure) and I remember those thoughts that I used to have and the thoughts that I still do--I remember my imagined funeral, of nights spent in horror that it will all end one day, of days spiraling at the lack of meaning of it all, existence a mirror of the infinite unpotential of space. I remember all of it and see all of it, all of me, in these three terrible people reflected back, cosmically failing over and over again. I remember and I see and I laugh.

The protagonists of Mojacko are losers. They're failures, both in their fiction and out of it, forever trapped in the shadows of Fujiko’s most successful works; immature idiots meeting death and escaping it time and time again by the skin of their teeth, world and audience laughing at them all the way as they scramble for meaning in a universe distinctly lacking it. They are nothing but a joke and everyone knows it. But they continue all the same.

If that isn't living, I don't know what is.2

Music of the week: K. Yoshimatsu - Marine Crystal

Sun-bleached pop on an old cassette; washed out and hazed songs of straw hats and blue jeans, beaches and faded photos. Beach music for sad lovers alone with nothing but the ocean and white sand, jangly guitars and cheap synths and vocals obscured by the hiss of the tape packed to bursting with nostalgia—both the good and the bad.

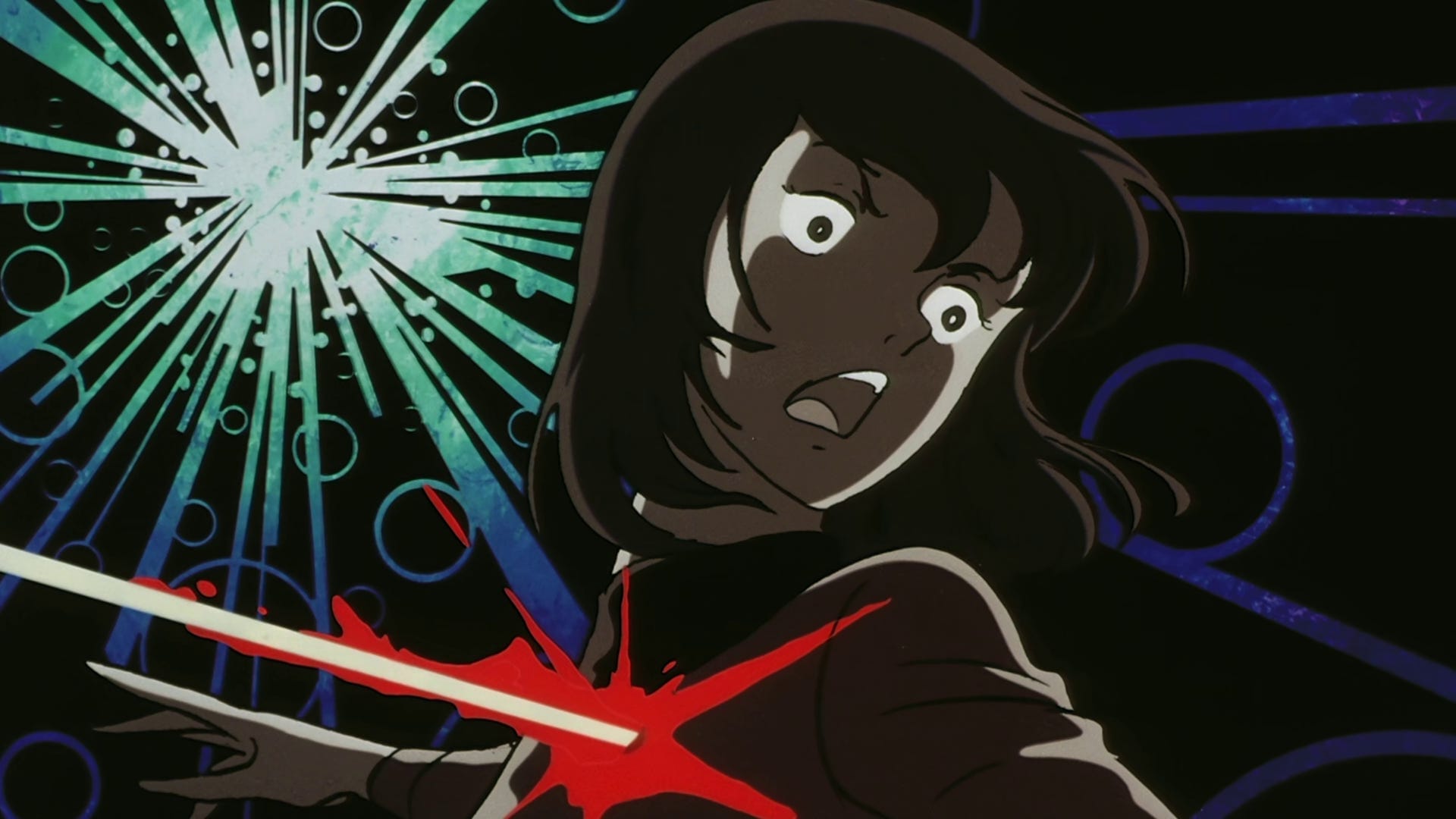

Movie of the week: Toward the Terra

The film adaptation of one of my favorite sci-fi stories of all time, Toward the Terra attempts the herculean task of packing a wildly dense manga into a quick two hours. And while it necessarily leaves behind a lot of narrative threads, it doesn’t sacrifice an inch of what makes the story so transcendent: a gorgeous, psychedelic opera that drifts through time and place like a dream, transforming sci-fi into a genre fueled by pure emotion, capturing the beautiful, dance-like movements of life like nothing else in the world.

Thanks for visiting! If you liked what you read, maybe share it around! It’d make my day :)

oh, and here’s the ultimate guide to good yuri media

The characters in Mojacko are essentially palette swaps of the cast of a previous Fujio title, 21 Emon, which this manga is a self-admitted retry of. ↩

Tragic, but as far as I know there’s no translation for the Mojacko manga right now, official or otherwise. Which like, hey! What’s the deal with that, world??? Get it together! ↩