Talking manga | Saint Muscle

Digging into the influential fleshbomb masterpiece and the biggest flex in manga

Deep among the rocks, where nobody can find it, there is a palace. It is large and gaudy, all pillars and arches and sculptures, and seems like it could house an army, even though isn’t anybody there. There isn’t anybody for miles.

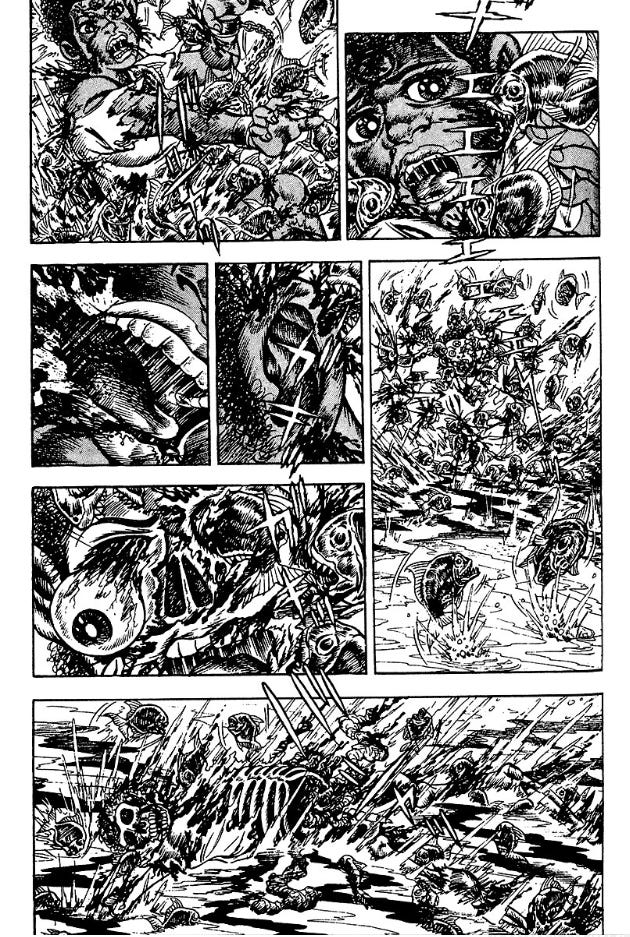

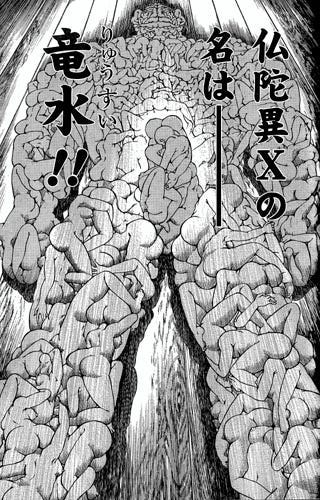

Walk closer, enter its walls and see. Something is awfully wrong about this place. Those are not pillars. Those are not sculptures. They are bodies. Every inch of the building, every brick, is crafted from tens of thousands of still breathing corpses, the ceiling an expanse of screaming, bleeding faces

And then, a voice from behind. Someone else is here, the owner of the palace. And they want to invite you to dinner.

There are not many stories more aptly named than Saint Muscle, the manga masterpiece from artist Masami Fukushima and writer Tsutomu Miyazaki that befuddled audiences and critics alike when it exploded onto the pages of Weekly Shonen Magazine in 1976. A bold and brash reinterpretation of the entire world though fetishistic muscle worship and mythic conceptions of masculinity, the series must have felt like an act of provocation, an attack towards its primarily male readership of the time.

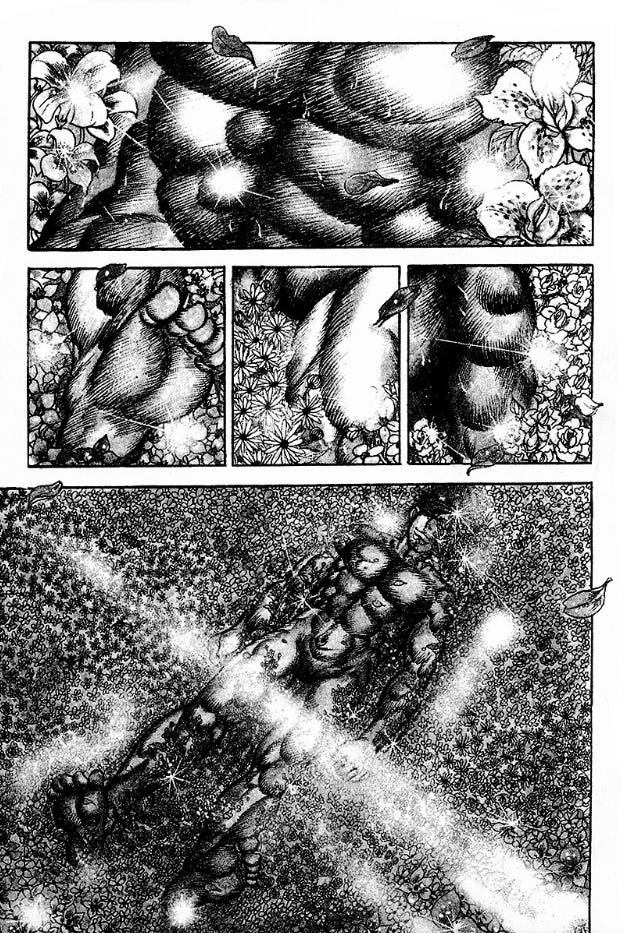

This was the age of gekiga after all, a movement (to greatly simply things) aimed at distancing itself from the childish image manga had developed, instead producing serious, often violent and experimental stories for adults. Even in the younger aiming Weekly Shonen — one of the most iconic manga magazines in Japan — any given issue of the time was packed full of sex and violence and dark celebrations of manhood. But Saint Muscle was different. It was not a celebration of being a man, but of men, one openly in love with the male figure, which begins with the hero, a veritable Greek god, naked and muscled to an inhuman degree, flexing alone in a field of pretty flowers.

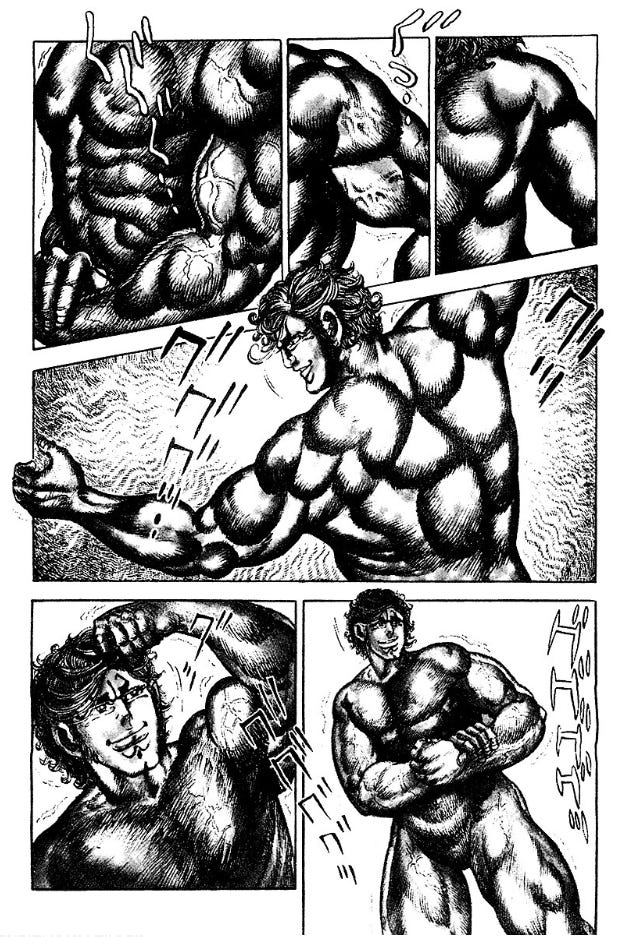

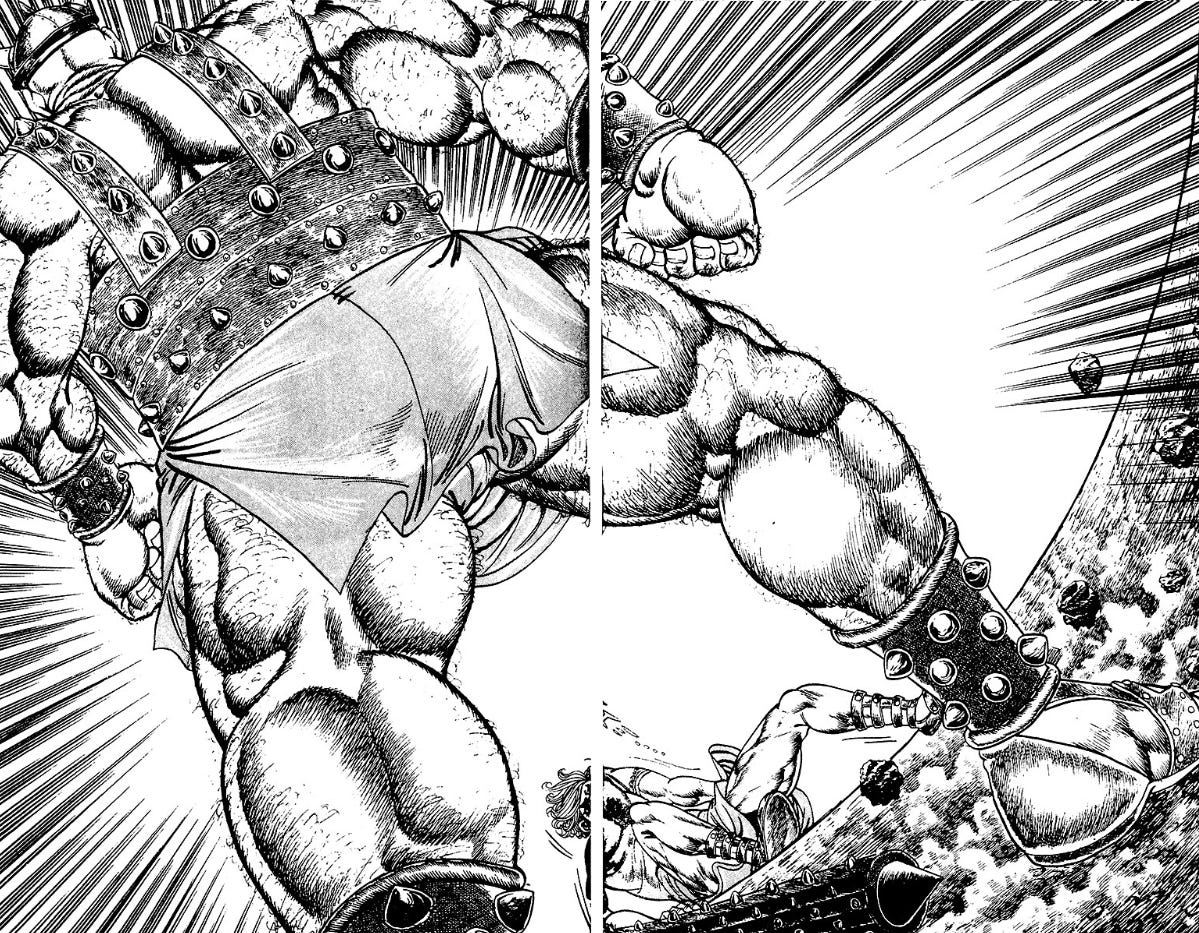

That man, the titular Saint Muscle, is a figure with no real name, memories, or clothes, perpetually traversing a wasteland in search of his identity. It’s a simple premise, allowing for endless self-contained stories within as he wanders into new town after new town, meeting heroes and villains and finding wrongs to be righted while proclaiming big, direct statements about individuality and perseverance. He is positioned as hero not only to the various characters he meets, but also the reader, a figure of powerful self-confidence who does what is right no matter what, and who never gives up in the face of injustice.

But then, the series’ real thematic interest is far more politically motivated than simple inspiring platitudes, very much fitting with its class-conscious gekiga brethren in a turbulent era. Saint Muscle depicts a world of rulers and slaves, a dead world where those in power hurdle the poor like sheep and literally build homes from their bodies. It is an apocalyptic reflection of our own, which sees capitalism continue to deepen the divide between rich and poor and perpetuate discrimination to ensure the power of the few remains in their hands. In the face of such reality, the manga is a cry, a howl at these systems of oppression and the violent status quo we are trapped in. The protagonist is not actually legend of the self, but rather a symbol to inspire change and revolution from the oppressed. Slaves give him the title Saint Muscle; he gives them the strength to topple kings.

Part of this political bent fury is undoubtedly thanks to the efforts of writer Tsutomu Miyazaki — a man with a long history in genre fiction, involved in what is considered the first doujinshi (fanzine) produced in Japan — who injects the series with the direct, grandiose simplicity of myth and legend, like Beowulf gregariously recounted by a drunk warrior. Just like our oldest stories, even the most minor moments and characters are turned into elastic symbols that can be stretched in a thousand different ways.

But make no mistake: Saint Muscle was artist Masami Fukushima’s story to tell. With no direct input on the contents of any given chapter — every scene, set-piece, action and movement decided by Fukushima beforehand, details relayed to Miyazaki via an editor — Miyazaki’s role was more like that of a benshi, or live narrator of silent films. He was there to verbalize and expand, to add his own context and flavor to a tale already told visually.

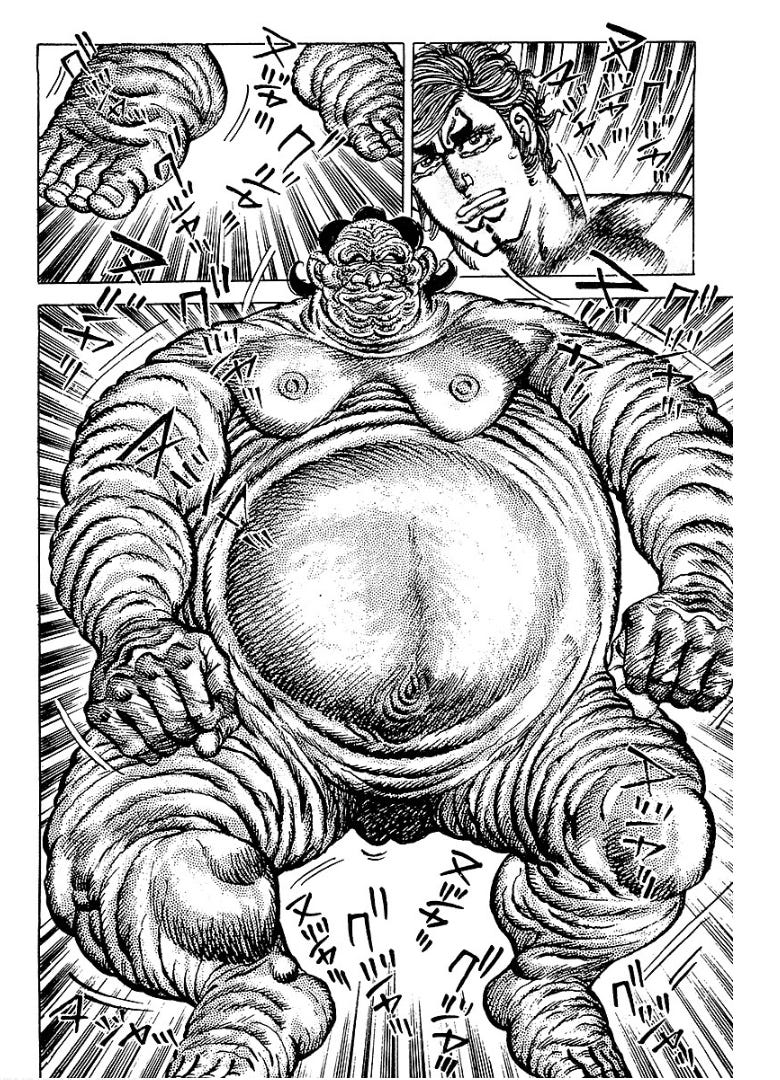

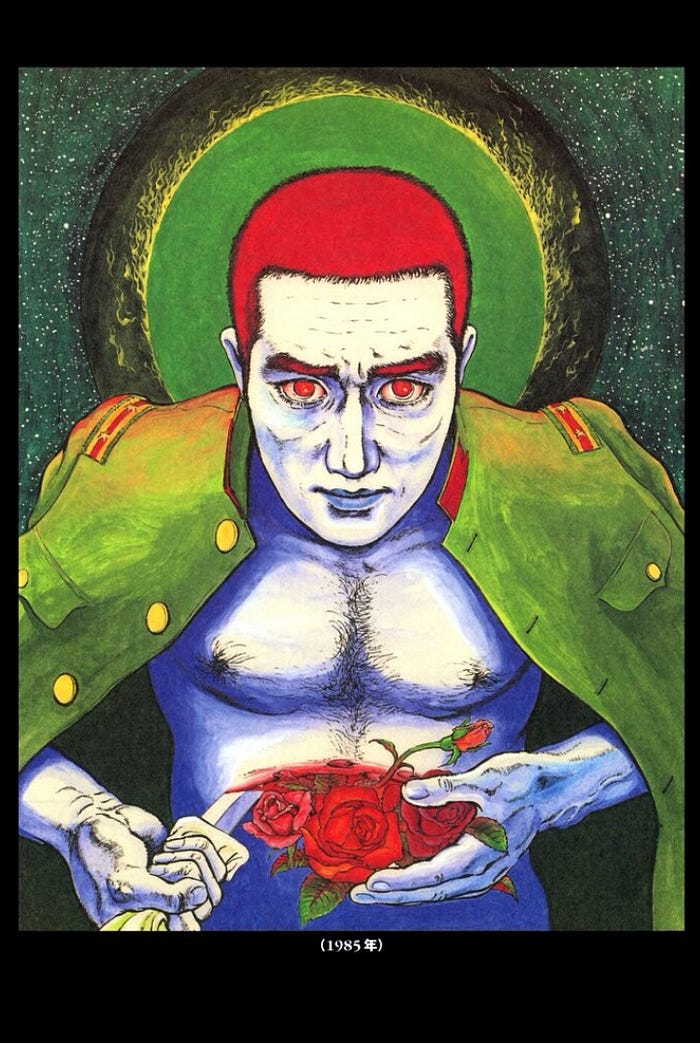

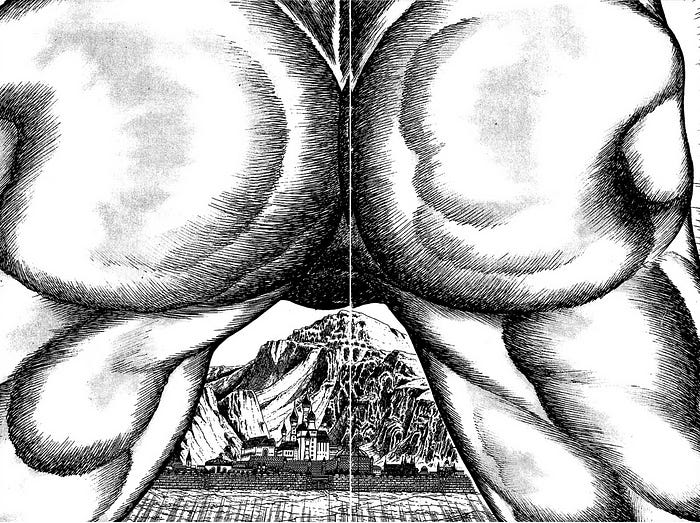

And what visuals. The manga is at once disgusting and erotic, full of sex yet distinctly lacking it, a deep understanding of anatomy used to re-imagine the body as an alien vessel of flesh, dripping in sweat and sensual detail. Thick thighs full of detailed leg hair; hanging guts with skin folded a thousand times over; muscles on muscles and where they shouldn’t be; naked bulges with nothing there. Nearly every character is a hyper-real exaggeration for whom scale is nothing but a plaything; towering giants one panel, pathetic ants the next, size decided not by reality but by their relationship to each other and the world. In climactic moments, hundreds of bodies writhe about in horrible collectives, paralleled by the perpetual cruelty of nature — volcanoes erupt and cities crumble in pages so densely packed that everything bleeds into one, sound effects splattered over the image like an awful cacophony.

This, a hallucinatory rocky apocalypse of a world, where scorpions fight on cliffs overlooking slaves dying, where freedom and power can only be glimpsed through the physical, is Masami Fukushima’s world.

Born to a cold Hokkaido winter in 1948, Fukushima was always acutely aware of the struggles of life among the working class, as well as the power of the human body. To support his family, he began working manual labor from the fifth grade up through junior high school, a shift towards manga in high school reportedly a financial one, driven by dreams of success in a rapidly expanding market. But from the beginning his work was too idiosyncratic for a mainstream audience, and he struggled through years of rejection letters and insults until a lucky submission to Osamu Tezuka’s COM magazine, a free-wheeling home for experimentation created in response to the similar and successful GARO, landed him a job as an assistant and finally opened the doors to publication.

After a few years of steady, but largely unsuccessful work, Fukushima unleashed his most infamous and enduring title, the salacious The Rapist Monk, onto the pages of Manga Erotopia. It was a shock to the system, an exploitation-filled re-imagining of Japan’s past as a pit of depraved systems, legends and heroes mutated into giant creatures of base instinct, their bodies converging on a grand, psychedelic scale. It was gekiga, yes, but not any gekiga the world knew, form pushed past the breaking point by this mysterious new enfant terrible. No, The Rapist Monk was something new to manga.

It was fleshbomb.

Called “nikudan” (肉弾) in Japanese, the fleshbomb movement could have only formed as it did in the 1970s, perhaps manga’s most radical period of innovation. Influenced in part by the exaggerated physiques found in American comics, here were a small collection of artists, like Fukushima, obsessed with the human form and muscle, exploring the base depths of us through physical extremism. Depicting the whole world through the body, the beauty and power and horror of the cage that traps us and gives us power a constant source of focus, the work of fleshbomb artists became increasingly experimental. What started as a violent push against the limits of gekiga gradually morphed into something more abstract, lyrical; logic and narratives falling away in favor of pure, powerful imagery.

It was thanks to the emergence of fleshbomb, and The Rapist Monk in particular, that Saint Muscle was born, Weekly Shonen editors so taken with Fukushima’s singular vision that they fast-tracked him straight into a serialized title, an unprecedented move for the magazine, and pushed an aggressive advertisement campaign with bold, loud previews of images such as a close-up of the protagonist’s bare ass in hopes of hooking readers through surprise. Before publication even began, there were whispers to Fukushima that awards were on the horizon.

It was a lie. After only six chapters, Saint Muscle was canceled, audiences bewildered by Fukushima’s idiosyncratic brand of excess. It looked strange and moved weird and felt decidedly out of place even among the work of magazine contemporaries like Go Nagai and Leiji Matsumoto. The unnamed protagonist was cursed to continue his quest forever and alone.

And for a while, it seemed like the Fukushima would be the same. After a few more years of single issue stories and short serializations mercilessly killed, Fukushima vanished. In nearly twenty years — from 1981 through 1999 — he published only one short story. Nobody knew where he was, what he was doing. Had he abandoned art? Gotten sick? Was he even alive?

In the decade following Saint Muscle, several long-running works crept out from its shadow to try and fill the void Fukushima had left. Fist of the North Star, Grappler Baki, Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure — blending gekiga with shonen, each is filled with outrageous muscles and fetishistic hyper-masculinity; extreme violence counterbalanced with ideals of aesthetic beauty. They are stories less concerned with the narrative than the image; the emotion of a scene, a fight, the way a body stands. But as great as Saint Muscle’s followers are, they were not the same. Fukushima’s absence continued to grow.

And then, in 1998, a message.

He was coming back.

He never disappeared again. Today, Masami Fukushima continues to consistently put out new manga while his older work is rediscovered by a new audience. Series long out of print and forgotten have been given new lease, and Saint Muscle has solidified itself as an underground classic, selling 30,000 copies when re-released to an age raised by its descendants.

Saint Muscle feels every bit as vital today as it did on release, nearly fifty years ago. It is still shocking and thrilling, uncomfortable and exciting. It fires off in the brain like a shotgun, wakes you up and demands that you look around. Our world is still a wasteland, those in power more bold than ever.

Never finding peace or answers, the man they called Saint Muscle is still out there, wandering in search of himself, fighting against what is wrong.

He has no name. He could be you.

Music of the Week: Oni no Migiude - Osharaka

A band headed by my favorite new age mysticism drenched sci-fi electronic artist Utena Kobayashi, Oni no Migiude’s new album applies her uniquely spiritual flair to…prog rock?? Here, dark folk music influenced by Japanese minyo and Indonesian gamelan among other sounds inevitably give way to wailing guitar solos, booming bass, and intricate rhythms without ever losing the energy of stepping into a forgotten mountain village that worships something more terrible than you could ever imagine.

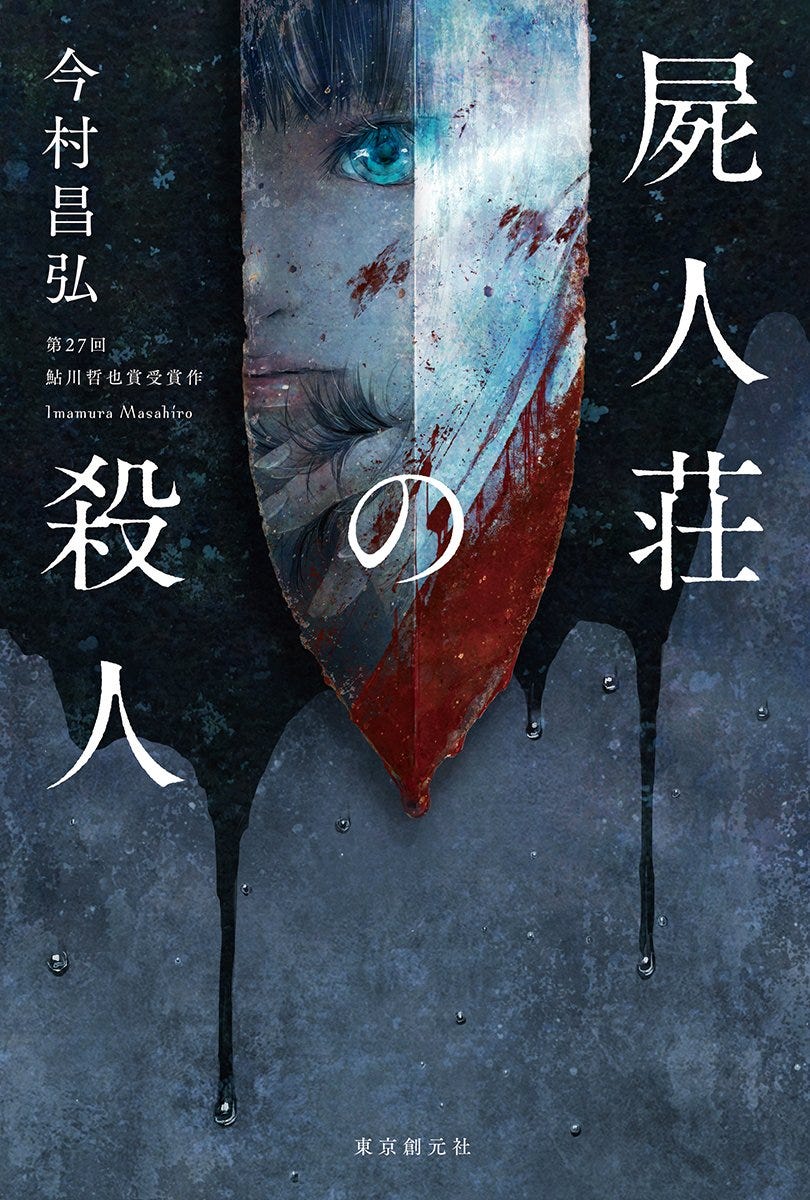

Book of the Week: Shijinsou no Satsujin by Masahiro Imamura

Known in English as Murder at Shijinso or Death Among the Undead (oof!), this debut novel blew up the Japanese mystery world when it released in 2017. Fiendishly, almost infuriatingly, clever, the book makes use of a certain classic horror monster to both completely rewrite the rules of the locked room mystery and act as a surprisingly potent metaphor for the emotional aftershocks of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Charming, immaculately constructed, and always at least one step ahead of you—basically everything you could want from a good mystery. Just be sure to avoid the movie.

Movie of the Week: Peach Baby Oil

Fifteen minutes of the stream-of-conscious anxieties of a young woman from director Junko Wada. The narrator whispers questions and uncertainties with beautiful poeticism, getting caught on phrases and ideas and repeating them over and over in a staggeringly honest way as the nude, unprotected body gradually takes up more the film. I haven’t been able to get it out of my head since I saw it—elusive and thus also as deeply relatable as anything I’ve seen.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here’s an interview with four essential anime directors who got their start in Tatsunoko Pro