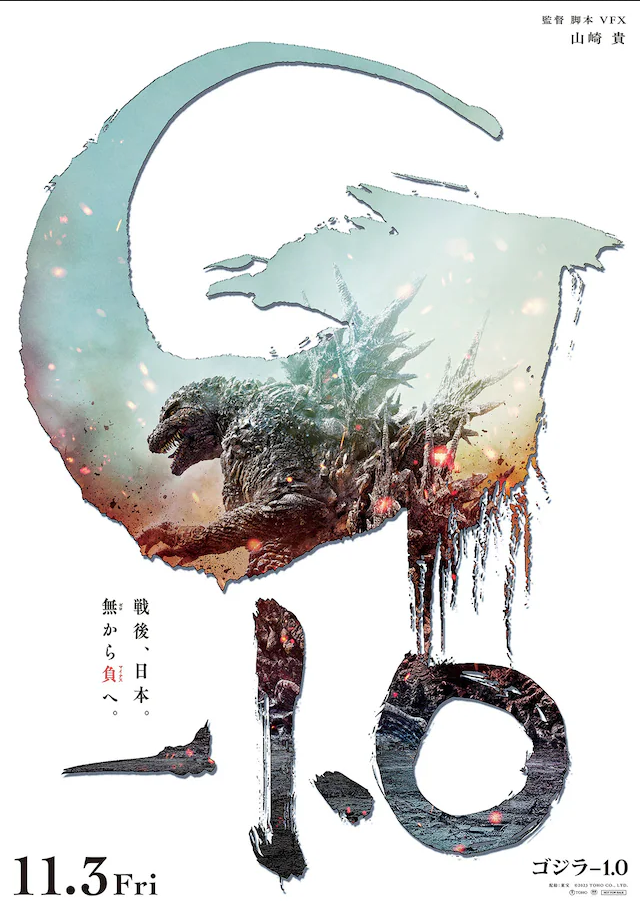

Talking movies - Godzilla Minus One

Reviewing the latest of the world's favorite monster

Godzilla isn’t just a monster. It never has been.

The world’s most famous kaiju is a thousand things: it is the nuclear bomb and nuclear power, pollution and the ineffectual government; it is the country’s unbreakable spirit, unchecked technological advancement, hope and despair, a hero for children and a warning for adults. Godzilla isn’t just a monster. It is everything, an infinitely pliable icon molded like clay to take on any shape it desires.

In Godzilla Minus One, the latest film in the storied Toho franchise, Godzilla is a shadow. Set immediately in the aftermath of World War 2, the appearance of the kaiju feels almost unnecessary. Japan is already a wasteland without the fantastical, a flattened hellscape of crumbled buildings and bodies; a place where living is a curse and to be a survivor is to be a sinner. The protagonist, Koichi, a kamikaze pilot who failed twice to sacrifice himself—first for his country, then for other soldiers—is certainly cursed, plagued by nightmares and ghosts that come at him like possessions. In the daytime he masks it, pretends to be human, but at night the truth seeps out; he rocks back and forth, screaming and clawing at himself, convinced that reality is just another dream. His guilt over living has destroyed him. His soul is the same as the rubble that surrounds him.

Then it appears. Giant, hulking, lumbering. It steps and buildings are blown to pieces, it howls and trains and ships are thrown across the sky, it hungers and people are chewed and ripped in two. And as crowds watch hopeless, their home torn from them yet again, it opens its mouth and another bomb drops.

The comparison is all but impossible not to make. In Minus One, Godzilla’s iconic atomic breath erases buildings and humans alike in an instant, eerie reflection of history. One second your loved one is standing next to you, the next there is only a shadow. It is genuinely horrifying, the specter of a war that should be over crawling out from the earth itself to repeat the destruction that we perpetuated against ourselves. The war, Godzilla roars, is not over.

This interpretation of Godzilla as a literal representation of the aftereffects of war—the scars and the trauma and the nightmares—is a potent one, ripe with feeling and honesty, speaking to a truth that will never not be vital. It’s a shame then, that director Takashi Yamazaki doesn’t give this idea the film that it needs.

Yamazaki is a conservative director in just about every way—politically, stylistically, narratively, you name it. His movies are movies that revel in schmaltz and sentimentalism, in big moments and even bigger emotions while romanticizing traditional values. He is, essentially, a director for Dads, the kind that loves to make flicks where soldiers solemnly salute men making the ultimate sacrifice for country and family. And that certainly describes Godzilla Minus One.

This is a movie filled to the brim with awed reaction shots from crowds and dialogue stuffed with grand, simplistic platitudes. “Please, live,” tough men say to each other, holding back tears. “This country needs you.” Many talented actors are present (Minami Hamabe my beloved…) but are largely forced into extremes to varying degrees of success, though it’s hard to blame them too much when the script renders even the most affecting Big Moment lines—“your war hasn’t ended yet”—into clockwork narrative beats. You will not find the bold, daring genre work that defines the greatest works in the franchise here; not the dizzyingly rapid editing of Hideaki Anno’s masterful bureaucratic horror-comedy Shin Godzilla here, nor the diamond-hard speculative sci-fi script-writing that Toh EnJoe provided for Godzilla Singular Point. You will instead find workman cinema. Filmmaking 101. What begins as a suffocation of despair and desperation transforms over its runtime into relaxed deep breaths as Yamazaki provides comforting reassurances on the power of conviction, patriotism, bravery, family, and community as a straggling group of survivors—some military, others not—come together to put Godzilla, and thus the war itself, to rest.

It’s hard to ignore how the film’s rigid populism and Yamazaki’s conservative storytelling simplifies and flattens its genuinely effective theming. It’s even harder to ignore when the film is released while all eyes in the world are on Israel and Palestine, as nations voice support for the slaughtering of thousands ostensibly in the name of “peace” and “justice”. We watch corpses line the streets while citizens share with the world their final moments. We watch mothers and fathers in Palestine hold up the brutalized corpses of their children. We watch them beg to be allowed to not wash their hands of their loved one’s blood because that is the only thing that’s left. How can you say that war can end by simply beating the monster? How can Godzilla, this immortal creature of destruction, ever hope to compare to the horrors we commit to ourselves? At best he can only ever be a shadow of us. And you cannot kill a shadow.

“Your war is finally over,” the heroes say; united, Japan has struggled past their destruction. But you know it is a lie, a fantasy. Scars might heal, but they never go away. And in the final moments of Godzilla Minus One, the same dedication to mainstream entertainment that dilutes its own message ends up—inadvertently or otherwise—suggesting as much. It’s a blockbuster after all, it has to have a stinger. There has to be the possibility of a sequel.

Just as war never really ends, its fallout lingering for generations, manifesting in ways we can’t imagine, so too will Godzilla never die, not really. We can kill him a hundred times over, burn his corpse and disintegrate him to nothing but atoms, but he will always be back. There will always a shadow lurking behind us.

Music of the Week: Cinema and Boy CQ - The Picture Show of Chronic Deja Vu

Theatrical gender-defying, film loving, shibuya-kei tinged idol duo that ooze uncaring cool while hopping through bangers, occasionally dipping into more experimental, glitchy electronic sounds. Like a hella queer, pastelled and intellectual spy thriller told through Tokyo's streets. In other words, complete idol excellence.

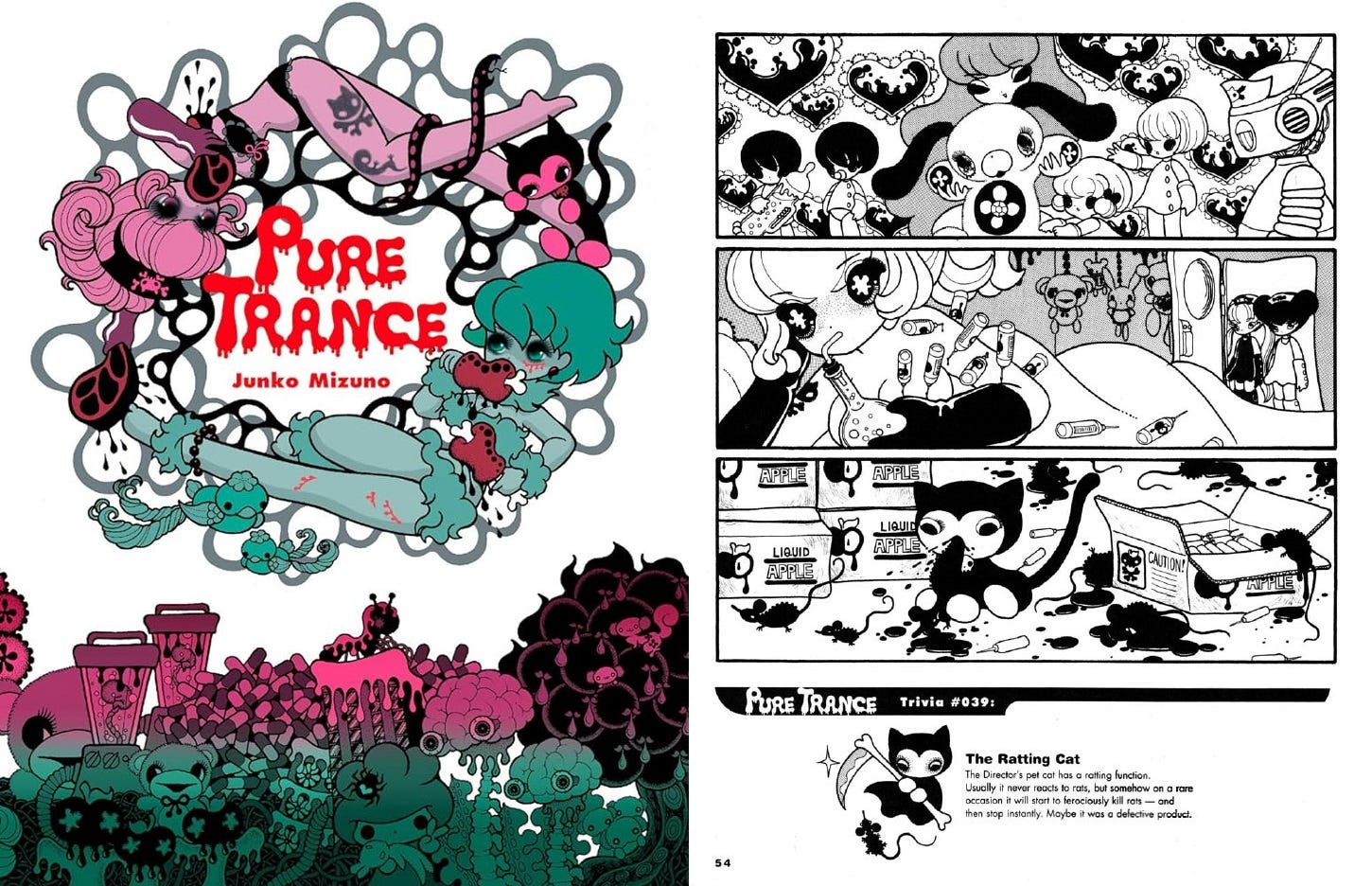

Book of the Week: Pure Trance by Junko Mizuno

Originally published in the booklets for a series of techno compilation CDs from record label Avex Trax, Pure Trance represents the debut of one of manga’s most distinctive artists. Trust me: it is impossible to mistake Mizuno’s work for anyone else. A post-apocalyptic sci-fi set in an underground city, there is a genuine discomfort in Mizuno’s art, hyper-stylized cute (think Hello Kitty) characters mutilating and assaulting each other, or sticking themselves up with a thousand needles as they have wild BDSM sex. Absurd, hilarious, bizarre, cool as hell, and one of the most completely singular manga there is. The kind of comic where you want literally every single frame printed on a shirt. Absolutely iconic.

Movie of the Week: Gonin

What begins as a taut crime flick about the dumbest people you know deciding to rob the yakuza transforms in its second half into a heartbreaking horror film as the cast is systematically picked off by an unstoppable hitman. It is gruesome and distressing and scary as hell, but director Takashi Ishii—who films with incredible stylization, shots bathed in lights and patterns that lend a dreamy, almost psychedelic air to everything—never once forgets the humanity of his characters, turning what could be obnoxiously nihilistic into a beautiful, expressionistic lament for the way minorities (the protagonists are poor, queer, handicapped, foreign) are crushed and abandoned under Japan’s conservative government. A feel bad classic.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here’s an awesome (and free!) zine covering some recent Japanese indie games