Talking movies | The Boy and the Heron

Reviewing the latest film from anime's greatest director, Hayao Miyazaki.

Hayao Miyazaki, the legendary anime director and face of Studio Ghibli, the man behind My Neighbor Totoro, Princess Mononoke, and Spirited Away, among a dozen other internationally recognized classics, has finally released what is very likely his final film. This is about as much of an event as there can be in the world of Japanese cinema, made only moreso by Studio Ghibli’s bold decision to only share a poster and a title with the world—no trailer, no frames, not even a synopsis or a tagline.

And in the spirit of that secrecy, I’m giving you lil stinkers not one, but TWO reviews of the movie!

First, some short spoiler-free impressions, then a longer piece going deeper into my thoughts on what the movie means (without really spoiling anything past synopsis level).

So here we are: my raw thoughts on an overwhelming movie—one that feels (to a dummy like me) impossible to firmly grasp with only a single watch. I hope you enjoy.

Quick Spoiler-Free Review (not a word about the plot)

There’s no question: How Do You Live? (or ughhh, The Boy and the Heron as it’s known in English) is all but assuredly going to end up the most divisive film in Hayao Miyazaki’s filmography, and it isn’t hard to see why. The movie can feel conflicted and lacking a sense of fullness; it doesn’t rouse or calm with the universal magic that defines so much of his career. In some ways, I think the movie might feel incomplete to some. Empty.

That’s exactly why it is a masterpiece.

This is Miyazaki’s Night on the Galactic Railroad1—a challenging, strange symbolist story that initially seems simple, but then stacks an impossible tower of metaphor on metaphor until you can’t tell which way is up. In two hours of frequently surprising animation (several moments made me audibly gasp at the abstracted way they depict violence), it runs through Miyazaki’s entire career, shining a light on every thematic interest he has ever shown, and then links them together into something impossibly large. It is an ocean of a movie with difficult conclusions to even more difficult questions, an entire soul depicted on film.

Night on the Galactic Railroad was only published after author Kenji Miyazawa’s death. He never truly finished writing it. Even today, nearly one hundred years later, bits of the novel remain elusive, just out of grasp, puzzling and enchanting readers as they fumble for understanding.

Miyazaki, thankfully, is still alive. And like Miyazawa, he still has so much to say. But it’s up to us now, not him (not them) to listen, to spend a life with How Do You Live?, swimming through its ocean to find all his words for ourselves.

A stunning, difficult, perfect summation to one of the greatest filmographies in the world.

Full Thoughts (Mild Spoilers)

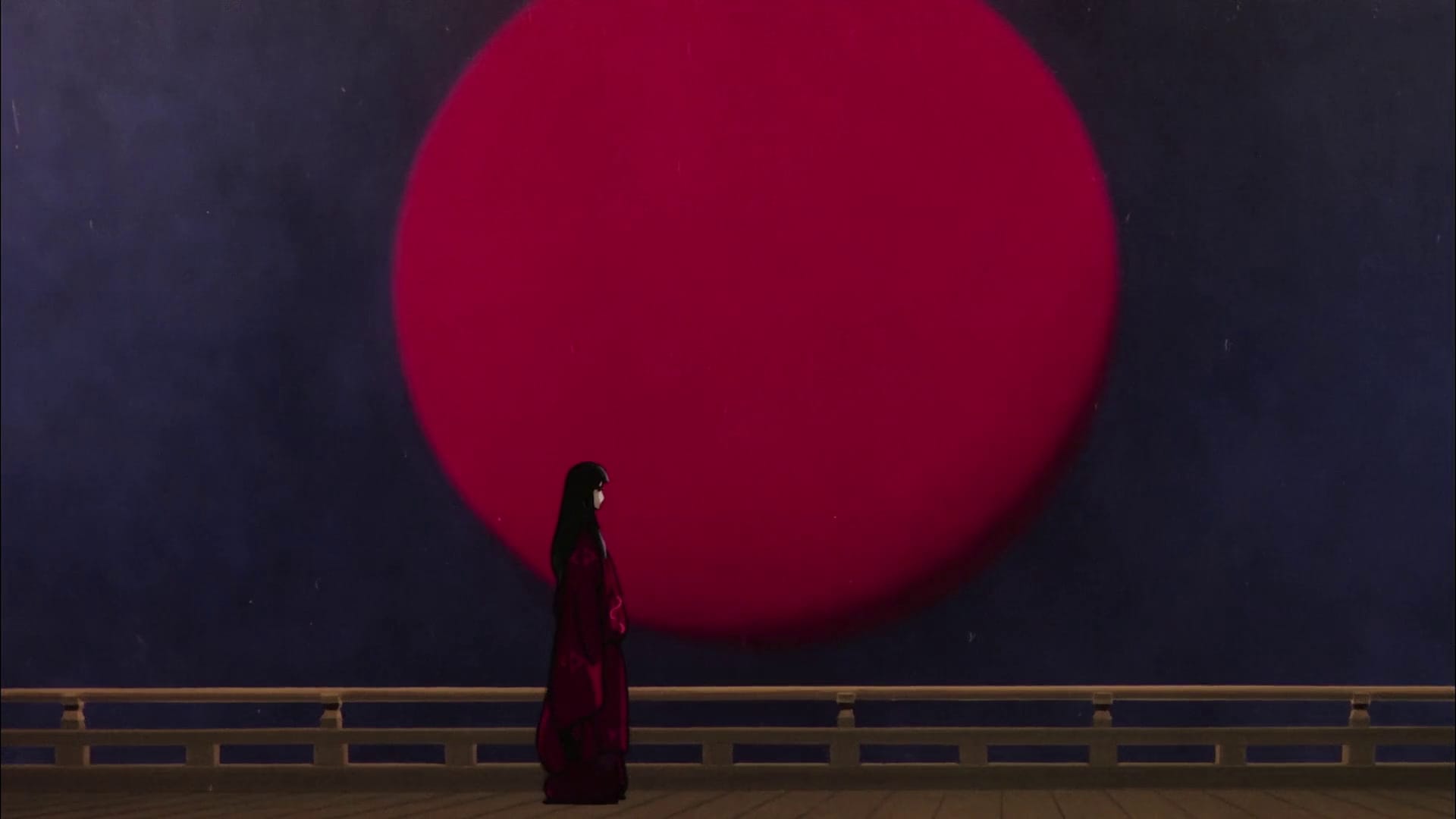

The heron is watching. It is a sign of death.

And surely there is plenty of death to go around. This is Japan in the throes of World War II, where loved ones are sent off to fight, never to be heard from again, where bombings have become a part of life, airplane identification records produced so families can know which cries above them are safe and which signal the end. Even in days of quiet, the sound of those metallic birds play while children make-believe at war, unable to comprehend what is happening around them.

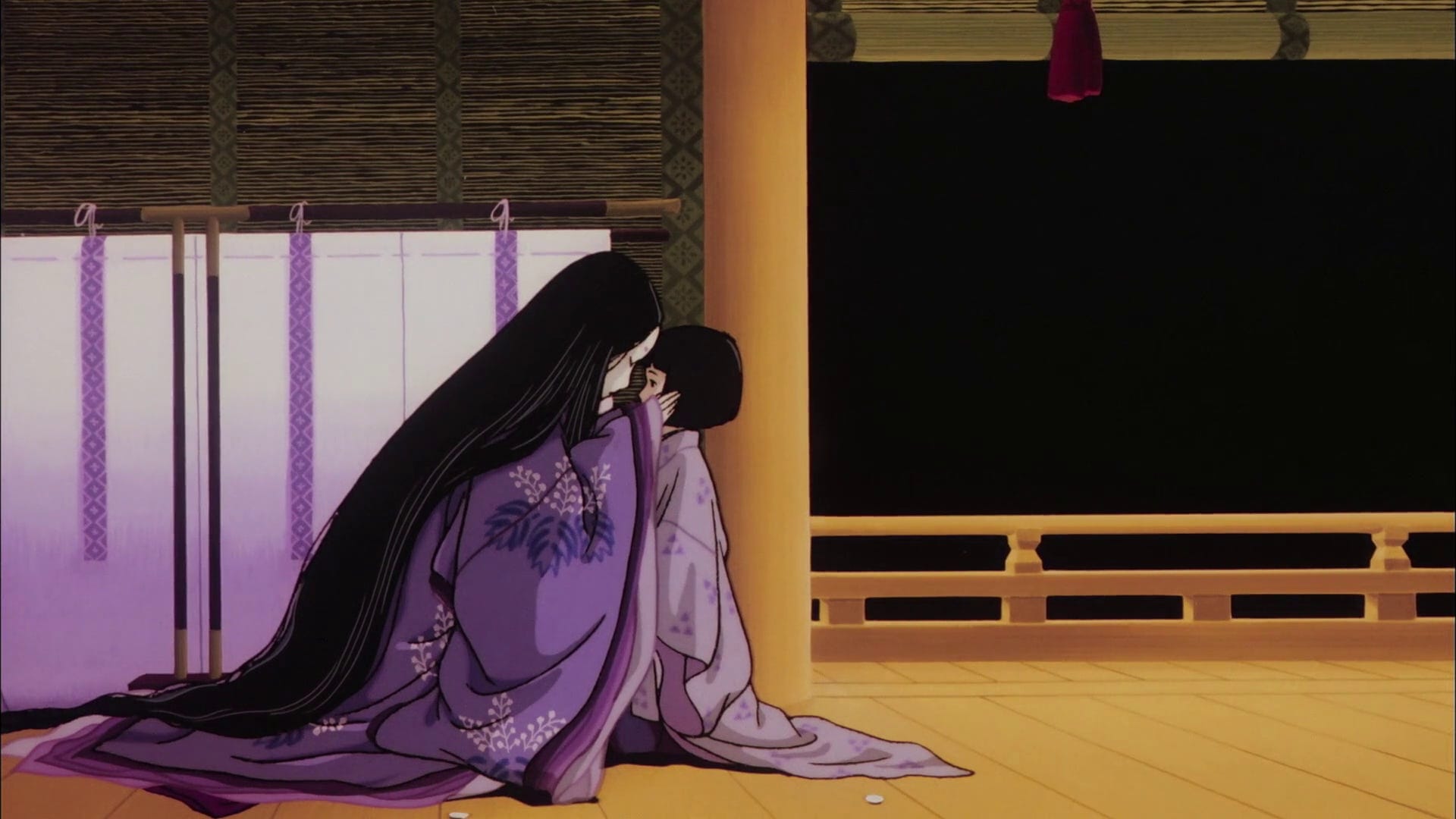

The protagonist of How Do You Live?, a young boy named Mahito, loses his mom in one of these bombings. The image haunts his dreams and follows him to the waking world, his father remarrying his lost wife’s sister, leaving Mahito to move in with a pregnant aunt who looks exactly like her. It is like he has been displaced from the world, living in an expansive and ancient home in the middle of nowhere with a ghost. Or maybe he’s the ghost—that’s certainly how he feels.

The image of her haunts the viewer, too. While much of How Do You Live? is animated with Ghibli’s characteristic style—warm and rounded and bright, with wonderfully observed naturalism heightened only an inch—moments of violence see the film break, as models all but melt into messes of moving line and color. The bombing, mere minutes after the movie starts, is a nightmare of movement, individuality collapsing as the distinction between person and person, person and building, building and earth becomes harder and harder to distinguish among the chaos and horror. When Mahito dreams of his mother burning, it invades the world like a torrent. It feels like the end. And maybe it is. Maybe everything since that moment has been the end.

Through all of this, the heron continues to watch. It is a symbol of nature.

Nature is everywhere in Hayao Miyazaki’s work. It’s ever-present, overwhelming. Time and time again, he explores humanity’s complex, contradictory, cancerous relationship with the world, whether that be through the furious war for progress in Princess Mononoke or the fable-esque iconography of a battle robot covered in moss in Castle in the Sky. There is a violence innate in our constructions, he seems to suggest, that we use for a war with the natural world. It can be seen as clearly as it ever has been in The Wind Rises, where planes are given an elastic naturalism, engine roars and propeller swings replaced with sputtering human imitation. Those metallic birds are alive, part of us. They are beautiful and evil and the most human thing in the world.2

Those birds are here in How Do You Live? too; Mahito’s father, working a munitions factory, has cockpit windows laid strewn around the house like graves. But there are also real ones. Birds populate the film by the thousands—big birds, small birds, birds for every color; fascist birds and oligarch birds, birds that liberate and birds that kill. Some are friends. Many are not. The humans characters often fight with them, but accomplish nothing but being covered in their shit.

It’s clear: these birds are meant to be human. But are they? They exist both natural and unnatural—they use weapons, frequently act as if lacking free will, and can be easily placed into a similar metaphor as the planes in The Wind Rises--blurring the sides of the war Miyazaki has been fighting his entire life until you can’t tell which is which.

And then there is the bird, the heron. There’s something wrong about it, something hiding inside of it. It is not like all the other birds; it is not what it seems. Death and nature. The heron begins to speak.

As the film it continues, turning a once grounded drama increasingly fantastical, war and death and birds and birth mix together until all of them are one and the same: the creator. Miyazaki himself. An old man, powerless and tired.

Miyazaki, like any artist, has dedicated his life to creation. That’s exactly the problem. Creating art is an endlessly contradictory act, one that places the artist on both sides of an inner war. It is the definition of freedom just as much as it is the definition of control; it is born from a desire to tell the truth but is incapable of doing that, only able to act like a mirror, reflecting back a flat image of what is really there. It inevitably destroys—whether that be nature in some way or lives through labor and finance, or unintentional ideological shifts—as much as it gives birth. There is no purity in art and there is no answer.

But sometimes you don’t need one. Miyazaki has spent a life and a career groping for conclusions that Make It All Work, each time coming back with nothing but air in an empty hand. In How Do You Live? he finally looks at that air and realizes it is exactly what he has been searching for this entire time. Everything is everything, and nothing makes as much sense as it should.

It’s a difficult conclusion, the idea that there isn’t one. It’s also beautiful and liberating.

Miyazaki is almost certainly done. It’s clear that he still has so much more to say. But even if he never finishes another film, even when he is dead and gone, I am sure Miyazaki will continue as he always has: swimming through an unending sky, guiding us all just as much as he guides himself towards that wonderful acceptance of air.

What better way to live is there than that?

Music of the week: pandagolff - IT’S NOT FOOD!!

pandagolff is one of my favorite Japanese bands out there right now, and their latest album IT’S NOT FOOD!! (aka what I say every time I try to eat natto) is the group at the absolute top of their game. Joyous, silly, genre shifting post-punk that manages to keep a real edge without sacrificing an ounce of fun.

From the Depths of the Hard Drive: The Tale of Genji

An underseen masterpiece from one of anime’s least appreciated geniuses, Gisaburo Ishii’s adaptation of part of the world’s “first novel” is a glacial, distant, and cold drama told through long takes and silence. It goes without saying that there is little in the medium as bursting with emotion. Unspeakably gorgeous with one of the greatest soundtracks ever produced (thanks to the legend himself, Haruomi Hosono), The Tale of Genji isn’t an easy watch, but if you open yourself up to its stillness, you will be rewarded with a hurricane.

oh, and here’s the most interesting (aka good) Best Anime Movie list I’ve seen

Night on the Galactic Railroad being one of Japan’s great classics of children’s literature by Kenji Miyazawa. Also generally just one of the best things ever written! ↩

There’s also ideas the film gets into (and which a lot of Miyazaki movies do too) about encroaching western culture overtaking Japan which parallels his talks on nature, but I’m not smart enough to dive into that. ↩