Talking movies | Kinki

Reviewing the latest from horror master Koji Shiraishi

Sometimes I think I’m more media than human.

I suppose that’s almost unavoidable in the modern age. With lightning fast internet and smartphones and corporations unlocking the science of the doomscroll, with more art of every kind available just a couple clack of the keyboard away, with the constant radically expanding amount of new things being created and released every single moment of every single day, how can you not be? Hours bleed together into swaths of consumption, where taking a break from a game means watching a movie, and decompressing from fiction means scrolling youtube and tiktok videos. With all of it, with everything, it’s natural now, I think, for your self to feel distant, for your very bones to feel like stories and games and products — to feel like anything except for you.

There’s no currently working director in the world today who understands all-caps MEDIA more than Koji Shiraishi. The meta-leaning Japanese horror director has built a career out of a deeply concerned interrogation of the medium of film itself, its reality and physicality and influence. Acting on the forefront of the fake documentary genre — a sort of sister to found footage horror common in Japan that presents its reportedly true videos of ghosts and ghouls as the kind of edited documentaries you might expect to flip past on TV — Shiraishi’s filmography is an ever-evolving beast in constant discussion with itself, peeling back the different forms video takes and the violence that lingers beneath.

I’ll spare you my breathless exaltation of his entire career (to be quick, I firmly believe Occult is one of the great films of the 21st century, A Record of Sweet Murder a beautiful thesis to his filmography, and the Senritsu Kaiki series basically his entire career arc in miniature) — all you really need to know is that Shiraishi has more than twenty-five years of work exploring our odd relationship to video and the even odder relationship held between those videos and the director of them.

And though he’s been working at a prolific rate since the late 90s, finding an early home in the then rapidly expanding industry of direct-to-DVD horror releases, it was with the 2005 cult classic, Noroi: The Curse, that he exploded into the consciousness of the wider horror world, taking the style established by series like Honto ni Atta and pushing it to an extreme, transforming faux-found footage of spirits into a procedural mystery of densely created mythology. There, the media itself becomes the point, the static of cheap video turning into a literal demonic force. There, horror acts as a form investigation, a series of interviews and journalistic research that slowly build a new, awful understanding of the world via the lens of cheap recording. In Noroi, it’s as if the movie is reconstructing reality through tapes and digital cameras.

And in that sense, his latest film, this year’s Kinki, might be the closest Shiraishi has come to returning to the iconic nightmares of Noroi.

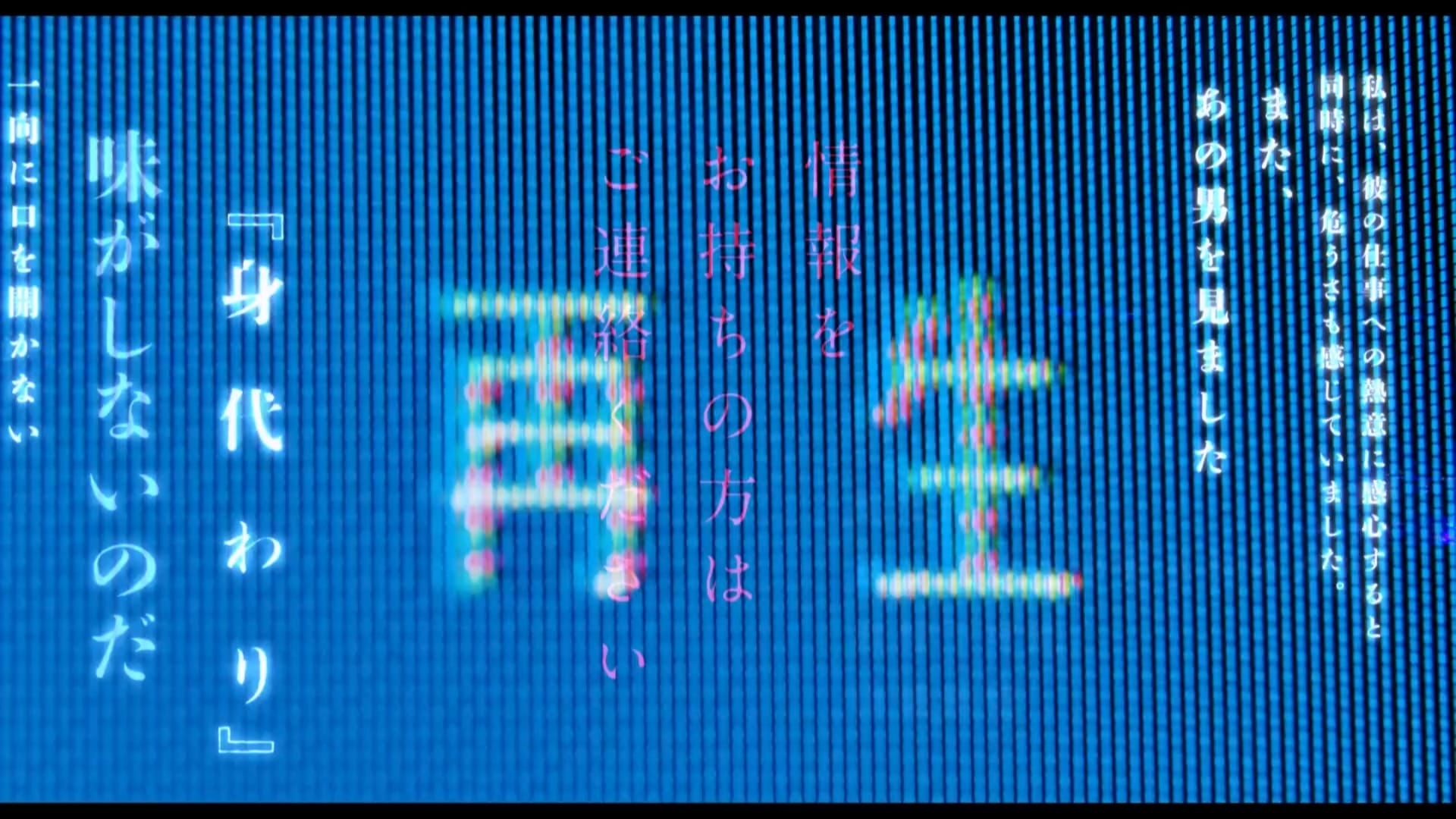

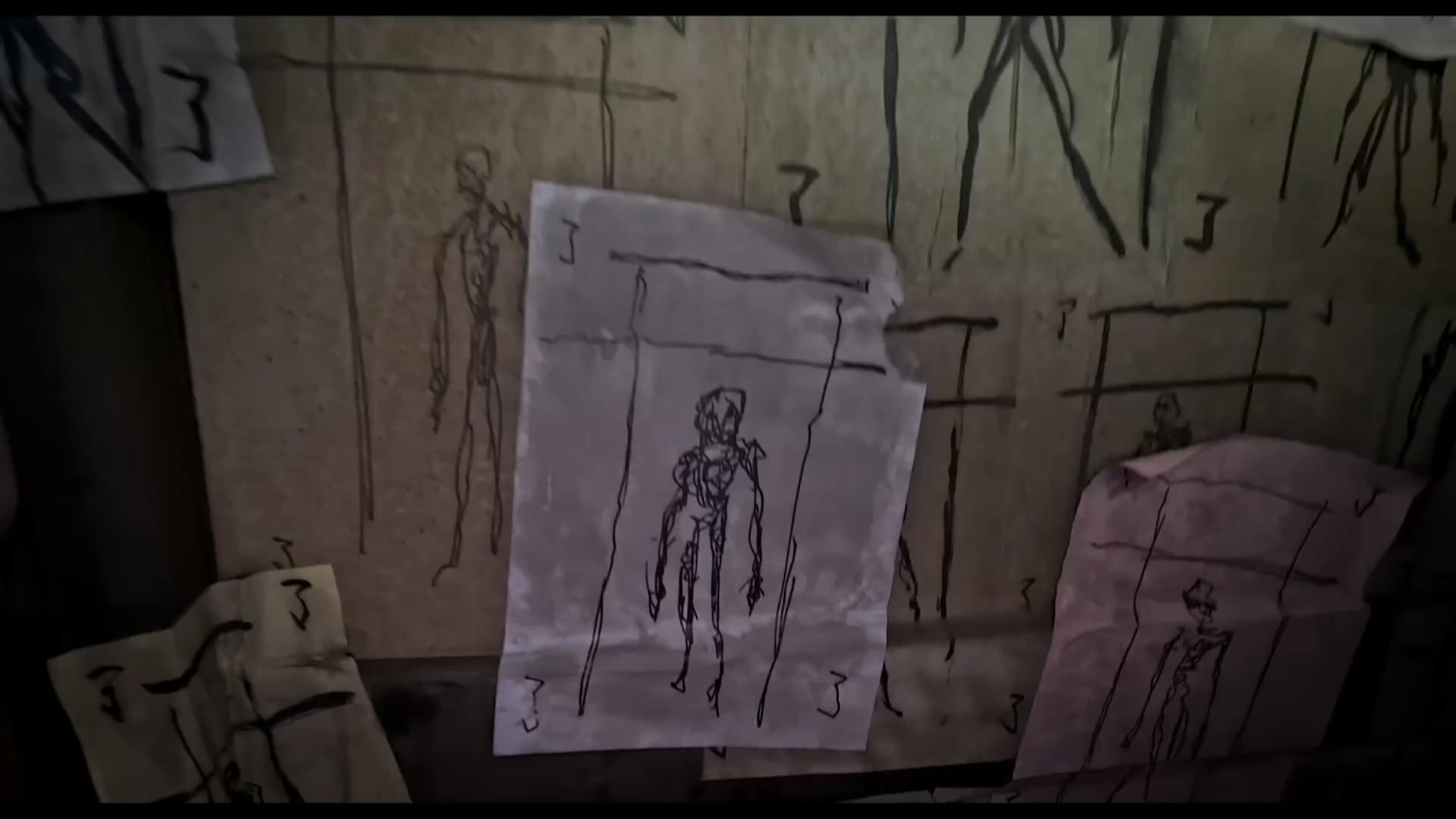

Following a staff member at an occult magazine and his freelancer friend who have been put in charge of a story about weird happenings in a certain area of the Kinki prefecture (the Japanese title — Kinki Chihou no Aru Basho ni Tsuite — would more literally translate into “Concerning a Certain Location in the Kinki Area”), Kinki presents itself as a procedural of the densest order, a story told via a collection of information that initially seems disparate but which gradually reveals a spider web of connections. More so than anything since, where Shiraishi has increasingly focused on his own role as an active participant in the propagation of pain, Kinki is a film obsessed with the puzzle pieces, with patiently slotting strange shapes carved from tapes into a grander picture of an awful, incomprehensible truth, one only noticeable through the great reality-shifter that is video.

It’s surprising then, that Kinki isn’t Shiraishi’s story. At least, not entirely.

Author Sesuji has recently burst into the Japanese horror scene like a world ending comet. With blinding speed helped by the kind of prolific publishing rate you almost never see in the English world, they have situated themselves into the new forefront of the genre — this exciting age where others like Uketsu and the Fake Documentary Q folks are pushing the blurred line of reality in horror — and for good reason: The original Kinki story, first published serially online and then in two differing book editions this year, is a stunning piece of genre writing.

Utilizing a found footage style but supplanted to prose, Sesuji writes much of their work (Kinki included) from the perspective of articles and interviews, transcripts of audio files and TV programs. They take an epistolary form — a through-line narrative emerging through the reoccurring writing of the journalist protagonist — and mutate it into an almost mind-bogglingly expansive vision of the modern world and how we interact with it. It’s a story and a style that revels in the ambiguity of media, in the blurring of reality in the face of how we present it. And then within that addictive push and pull of mystery and answer, they create horrifying eldritch suggestions, whispering in the corners of a broader mythology of spirits and the occult that makes one thing perfectly clear: no matter how much we might see in a video, it’ll never even come close to the truth.

Sesuji feels, in other words, like the world’s most perfect, natural fit collaborator for Shiraishi.

Here’s the thing though: despite all that build up I just gave, unlike Noroi and unlike Shiraishi’s career in the field, and unlike Sesuji’s style the film is based on, the Kinki movie isn’t a fake documentary. It isn’t even found footage.

Kind of.

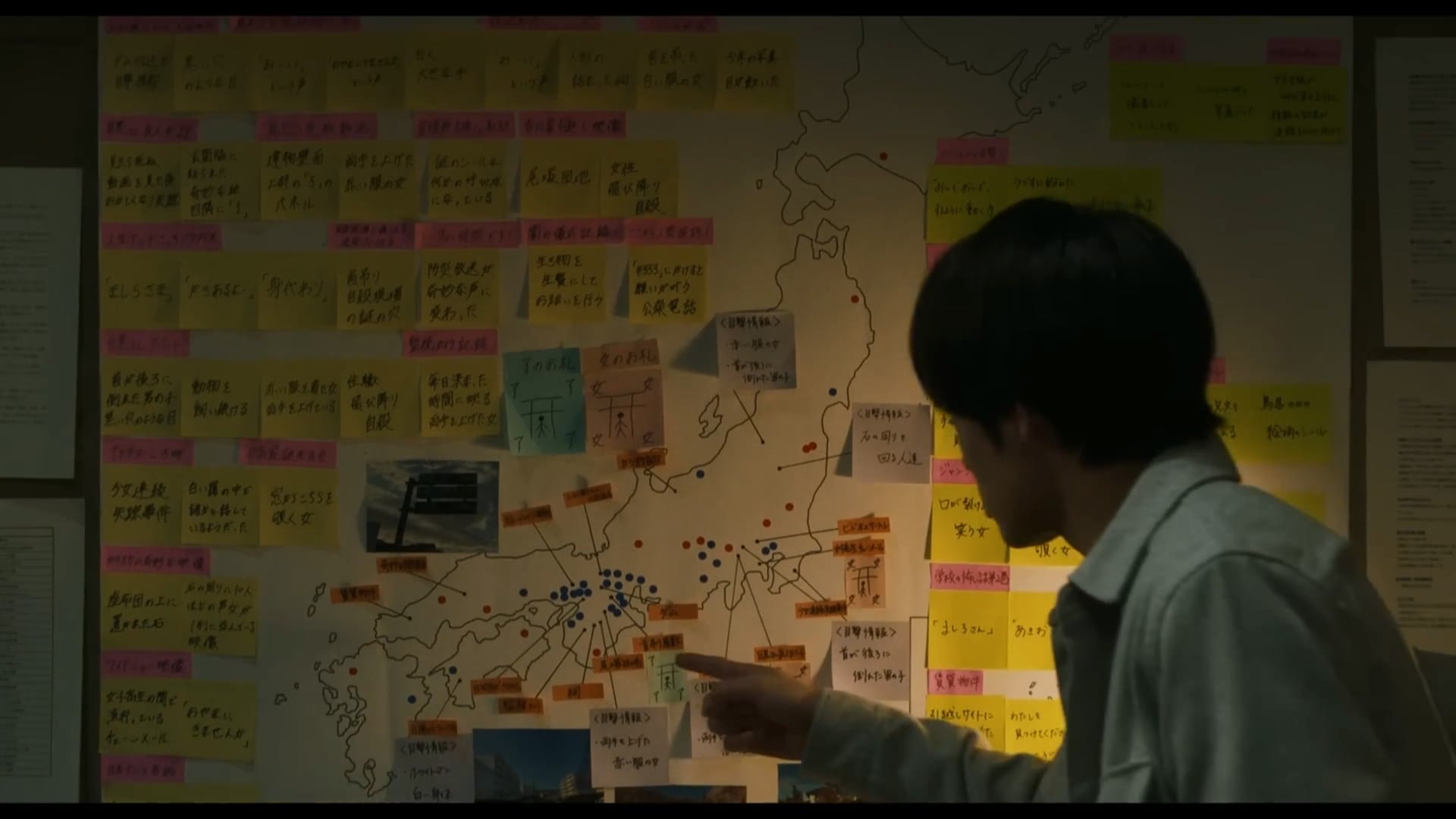

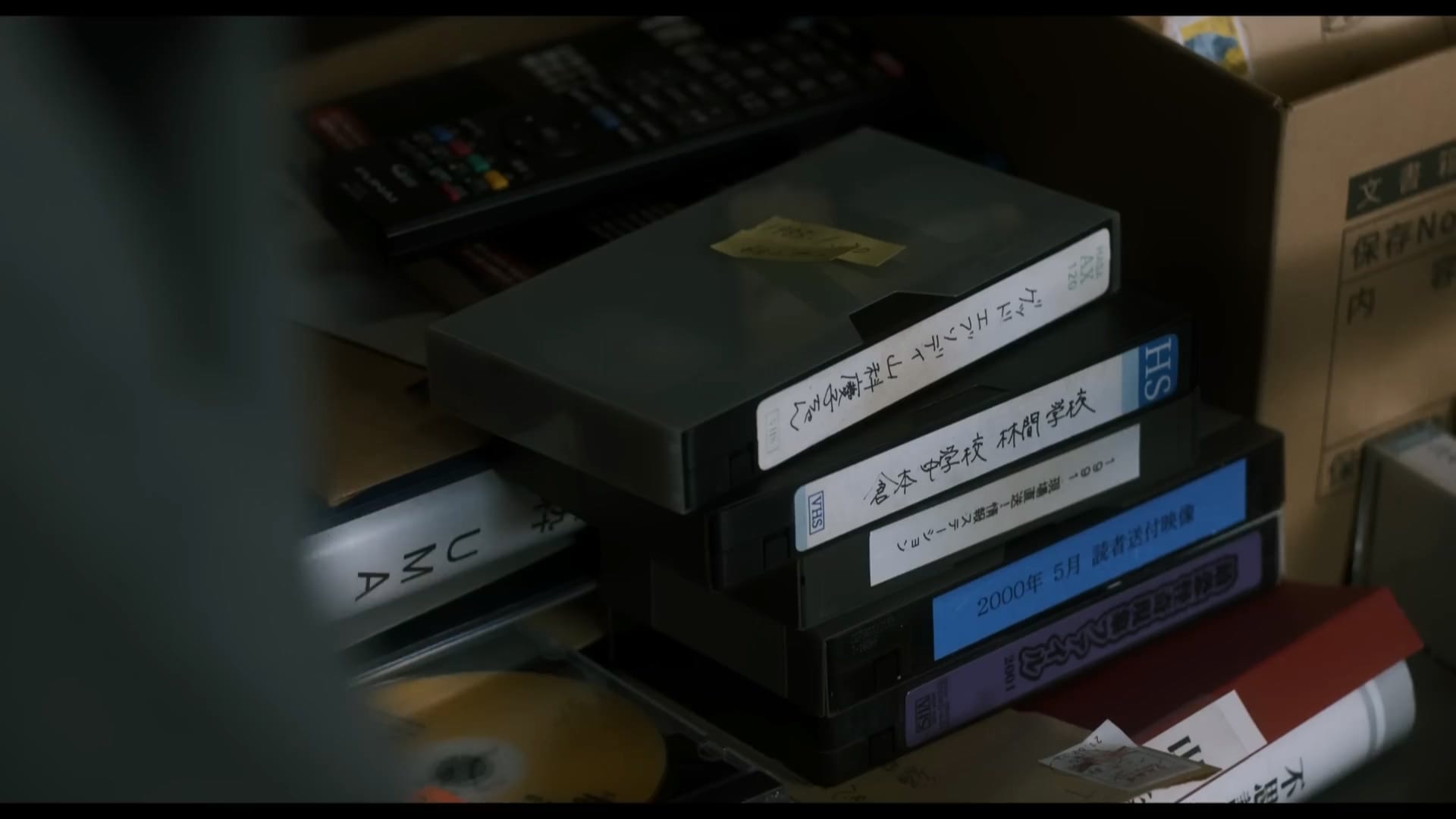

A blending of two forms, Kinki places its found footage within a traditionally staged film, third person segments acting for much of its runtime as a glue to connect its series of old television programs and forgotten internet videos. For truly at least half of the movie, we watch patiently as the two reporters sit in an archival room, walls covered head-to-toe in shelves of books and binders and boxes of paper, and show each other old magazines, cheap DVDs, USB drives squiggled on with marker, hand-drawn notes and maps, VHS tapes bought for homes long gone.

It’s absolutely electric. By partially pulling out of the fake documentary world and grounding itself within a more distanced perspective, Kinki has become the Shiraishi film most directly concerned with physical form of media itself, with video and text as objects beyond their contents.

In the age of digital, it’s easy to forget the physicality of film. It’s easy to forget the physicality of all art. Games aren’t just ones and zeros — they are things you control, use controllers of a thousand shapes to interact with, objects that come in boxes and cartridges and disks and machines, but boy it’s hard to remember when you buy them all on Steam. Paintings are layered and have depth, clumps of color and shape bulging out, but all that’s invisible to a JPEG and a monitor. Books aren’t simply the idea of words — PDFs downloaded to a phone — but a collection of them placed in careful order and shape and size on paper in equally considered order and shape and size.

Early editions of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass were published in large, oddly shaped tomes with detailed embossing, a profound reflection of the massive, earthly, elliptical poem contained within. But as Whitman changed the contents—including removing the suggestive ellipses and adding a definitive period to the end of “Song of Myself” — the book became smaller and fatter, both denser and more pocketable. Now, any given release of the collection looks like any other. Now, you just google it and read it off a website.

The format art is presented in matters. The subtle physicality and various shapes a work fills space with shifts the way we think and interact with it. And in the modern age, that form has become increasingly homogenized to match our increasingly bottomless consumption. (You all should be so proud of me for resisting the urge to go on a Whitman tangent for this long, btw.)

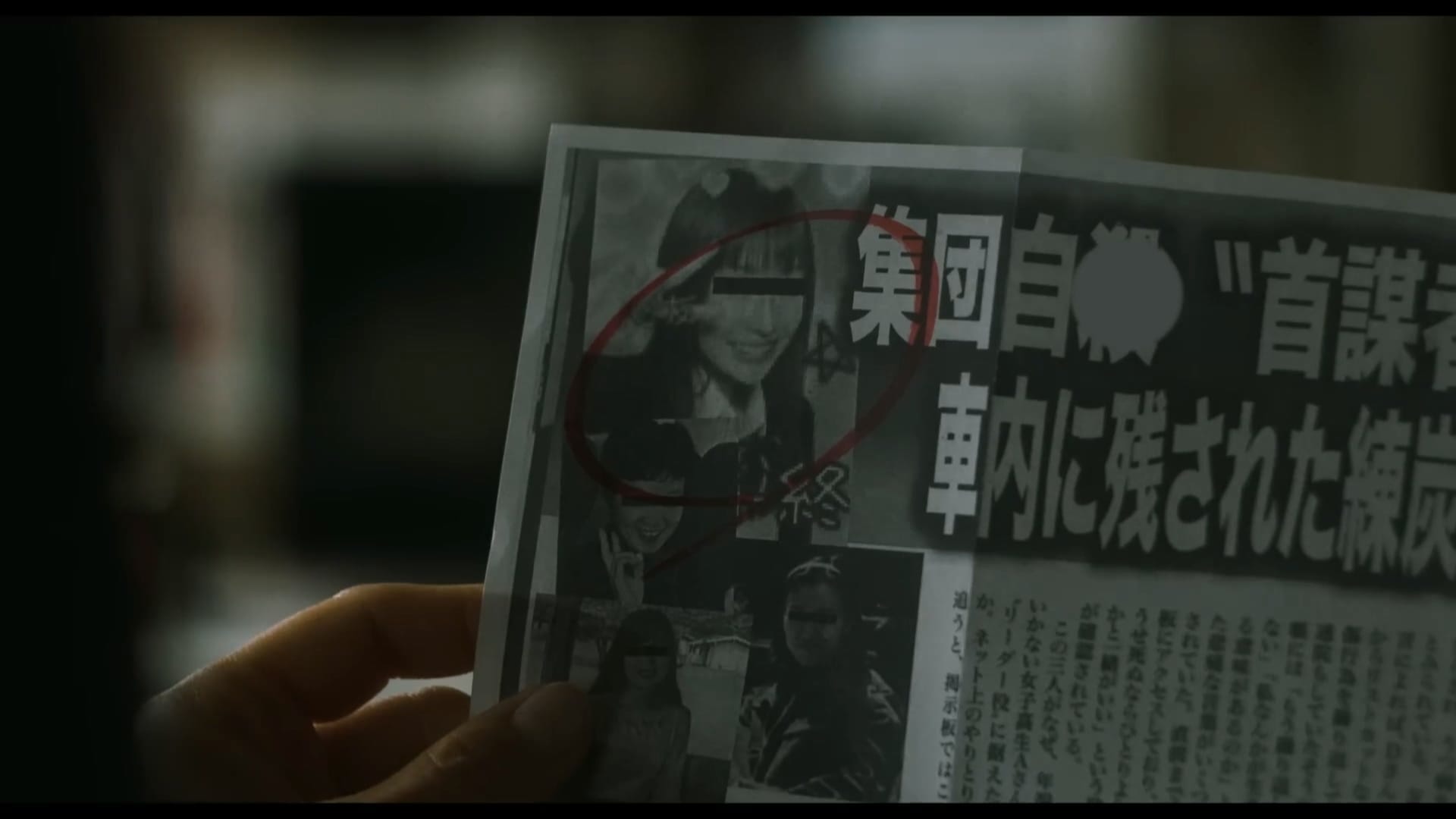

In Noroi, which is presented as a documentary within its own fiction, there is a constant sense of immediacy, a sense that everything is connected, all part of a singular whole. This is largely how it is with all fake documentaries. Content is king in the genre, not the vessels that carry it. A VHS tape isn’t a VHS tape, it’s another layer to dive deeper into the mystery of the film in the film you are watching. Instead, these films are more fascinated with the unique peculiarities that are born from form, the haunted possibilities granted to types of media that can die. Tapes deteriorate, CDs scratch, paintings chip and early digital images dissolved into pixels over time. The shape art takes changes its contents, too.

But through the distancing of staged sets, impossible cuts, and clean, static imagery, each piece of media shown in Kinki becomes significantly more weighted. The camera here lingers on their formats before they play, highlight the physical presence they have. It wants you to notice and sit in the real world presence of what you watch, of the concrete history the horrors of the film occupy.

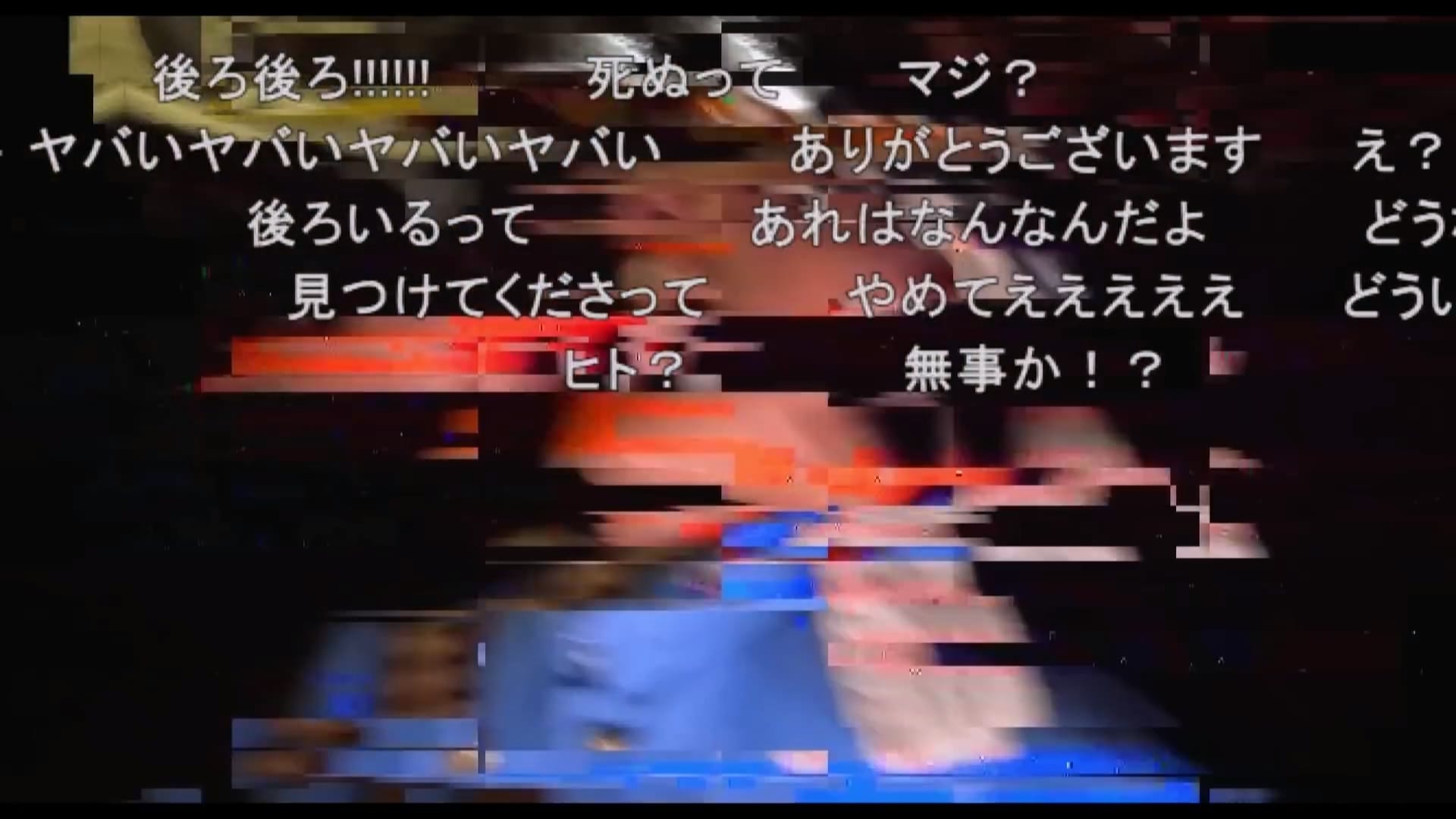

Not that the found footage material itself here isn’t fantastic. Indeed, it’s some of the strongest work Shiraishi has ever put out. Maybe it’s in par a bias of finally getting to see this stuff on the big screen, but there is a particular moment found in the movie — a tiny little minute or so long video left on a USB — that I’m half convinced is the best moment of filmmaking in Shiraishi’s career thus far, pushing the found footage aesthetics beyond the breaking point into a fully avant-garde screaming slab of violent montage. Friends, my jaw was firmly on the floor.

But the real magic of the film is what happens as it goes on. The reporters leave the basement of files and history. They take a digital camera and begin to film for themselves. And gradually the two styles of filmmaking begin to overlap until they might as well be one and the same.

By the end of Kinki, the distinction between found footage and staged has blurred into nothing, image freely switching between the two as naturally as one might cut between characters in a shot-reverse-shot. It hops ceaselessly between the ”objective“ (a lie of a word, as it’s really the viewpoint of Shiraishi) and “subjective” (the character filming within the movie) as horrors beyond comprehension make themselves known. For us, the viewer, the fuzzy handheld recordings seem more authentic, more real to life; for the characters, those same recordings are the only way to compartmentalize the nightmares they are faced with. Only by abstracting it into media right then and right there can they accept it.

I won’t spoil where things go (if you like Shiraishi’s wilder lore swings, you’ll have fun with this movie) but I will say that the movie ends as it begins: with phones, with the internet, with social media, with a flurry of voices and noise in every direction, with that plethora of media we can touch and feel — the video camera, VHS, USB, CD, magazine, book, newspaper, film reel, paper and pen — nowhere to be seen. What was so cleanly delineated early on in that archival basement has completely collapsed. The forms are not separate from us anymore. Like Noroi, like Sesuji’s stories, like Shiraishi himself in everything he does, there is no difference between who we are, what we watch, and how we watch it. It’s all just there, perpetually floating and screaming without rest.

So maybe it’s not just me. Maybe nobody is really human anymore. Maybe all that’s left of us are tapes in forgotten rooms and videos on YouTube.

Can’t think of anything much scarier than that.

Music of the Week | Punch the Monkey by Various Artists

A collection of remixes of music from the rascal thief Lupin the 3rd series, transforming the franchises' iconic jazz score into club bangers thanks to a host of major talent in the scene. It was also, fun fact, made into a not very good rhythm game for the PS1 that I almost wrote a post about years ago! If you ever wanted to know what Fantastic Plastic Machine or Pizzicato Five could do with Lupin, well...it's as good (and funky) as you'd expect.

Book of the Week | Smith, My Friend by Kaho Ishida

A short novel about a woman entering the world of professional body building, Ishida writes this first person drama with the clear-eyed, matter-of-fact messy interiority of contemporary classics like Convenience Store Woman and The Woman in the Purple Skirt (the biggest compliment I know how to give anything). The narrator here is such a perfectly realized character, so wonderfully true to life with her obsessions and desires and confusions and petty pride, that it’s enough to almost make me forget I’m reading fiction at all and not just peeking in a brain. Wonderfully fun and wonderfully complex.

Movie of the Week | Sadako DX (dir. Hisashi Kimura, 2022)

One of my most nuclear hot takes is that this recent, off-the-rails and maligned entry in the Ring franchise is actually a secret heater. A weirdo COVID comedy that barely even pretends to still be horror and instead acts as a gonzo self-reflective examination of the status of a franchise that has, essentially, imitated its own curse, Sadako DX manages to mine actual, honest-to-god ideas in a series that probably should’ve stopped decades ago. Vulgar auteur as hell, and I’m not going to pretend that the end credits didn't make me weirdly emotional.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh and I was on a podcast for an unhinged deep dive into the manga Saint Muscle