Talking movies | Look Back

When reviewing a movie means reviewing yourself

I’ve wanted to be a writer for longer than I can remember and that isn’t any kind of exaggeration. My memories start with me writing stories, which means I start with writing stories. In elementary school I’d spend my free time making a novel or multi-page book reports or memoirs; in high school my grades collapsed (partly) because I got too focused on writing; in college I studied it and got a Definitely Not Useless degree in English because I like to write and I like to read and that’s all there is to it. It’s all I’ve ever really wanted to do, all I’ve ever wanted to be.

So why am I still no good at it?

Look Back is a story about two artists, but it’s also a story about only one. Adapted from the short manga of the same name by modern manga icon Tatsuki Fujimoto and gorgeously, delicately directed by Kiyotaka Oshiyama, it’s a film about the evolving relationship between said two manga artists from elementary school through adulthood that will, if you have even the slightest inclination towards creating art, tie you up villain-style to the tracks and hit you with a freight train. If you like to write, if you like draw, if you like to play music or make games or sculpt or design or whittle or do flower arrangements or cook or dance or a thousand other things, Look Back will hold you up at gunpoint in Emotion Alley and mercilessly pull the trigger.

I say “creating art”, but that’s not really true—or rather, it’s true because near everything out there is art in some way or another. It’s all about passion, that immaterial, undefinable zeal for anything that defines Look Back in the same way it defines all of us.

Of those two characters at the story’s center, Ayumu Fujino, the lead, is conceptually talented, possessing a limitless imagination and innate sense of narrative rhythm. She’s appropriately given to emotion, filled with confidence one moment and self-doubt the next, simultaneously down-playing and over-exaggerating how much she tries and how much she cares, lies spilling out of her mouth to fit a character and an image she’s built up from a slurry of truths and fictions.

The other, Kyomoto, is quiet. She doesn’t know how to talk to others. She doesn’t know how to go into the outside world. She just stays locked up in her room, drawing day in and day out, and if she isn’t drawing then she’s reading, studying from the work of others how to improve her own, giving her an incredible artistic talent while distancing herself from the world.

They’re as different as they come, diametric opposites. They’re also the same person. They’re all of us; you and me.

Like Ayumu, I am constantly saying what I don’t mean, obfuscating my efforts in vague it-was-nothings and I-wasn’t-really-trying-with-this-ones when of course I actually did try, very hard, forcing pride or excitement about my own efforts down to only be expressed when I’m alone. Like her, I see the work of friends and constantly feel jealous or worthless, feel the urge to give up and pack it all in well up in my gut. Why is my vocabulary so small? Why am I so poor at research? Why do I seem incapable of writing fiction that connects emotionally? An infinite ocean of whys covered up so others can’t see.

Of course, there’s also more Kyomoto in me than not. Like her, I’m not the best at talking or connecting. I can’t handle crowds too well and spend most of my time holed up in my little apartment with art and stories. Like her, I hesitate to share, feel embarrassed by it, and like her, my own work is too wrapped up in the work of others. There always seems to be something missing.

This idea of the two characters as a symbolic whole representing any self-styled creative person isn’t a stretch. It isn’t even subtle. When the two start working together and beginning professionally publishing manga, they combine their names to make the pseudonym Fujimoto, eventually leading to their Chainsaw Man-like series, Shark Kick. They are Tatsuki Fujimoto in the same way they are all of us.

Fujimoto has always been deeply preoccupied with our relationship to fiction. Starting with his first serial (I haven’t read is short work before then), Fire Punch, he’s found himself working in deeply meta-textual grounds, that exploitation anti-shounen evolving through its run into a wild exploration of traditional narrative structures as faith, how stories we tell about ourselves actualize through belief in ways that both free and constrain us. His smash hit Chainsaw Man acts in similar ways, reconfiguring those ideas and using them to point towards the ways systems of power abuse these stories for fear and control. In both of these, and in his more contained Goobye, Eri, film plays a major role, acting as the defining, go to representation of art.

So what could Look Back, this story about manga, be then, if not a movie?

It’s perfect for a film adaptation and perfectly adapted to boot, screaming from every frame, every stroke, every molecule about the value of animation. Could you tell Look Back in live-action? Yes! Could it be good? Also yes; I can imagine a director with the proper restraint and understanding (think along the lines of Nobuhiro Yamashita) could have created a very strong film from the material. But I’m glad they didn’t, because Look Back belongs here. This is form as meaning, the very nature of it being an animated film bolstering and deepening its thematic power, paradoxically bringing the story into the real world a thousand times more potently than a live action adaptation ever could.

It’s also an intimate film, not only in story but in construction. Look Back might only be an hour long, but it spends much of its hour in silence and stillness, delighting in carefully observed character work and the pleasures of just watching someone work. But even in its most low-key moments, it’s packed with an almost unending stream of surprising editing and thrilling visual metaphors. In only the first few minutes you enter the world of a comic strip, watch manga-like panels pop up, and see a small classroom multiply until it’s an entire, suffocating world. It’s electric. It’s profound.

And then tragedy strikes.

For once I won’t spoil where the story goes (even though I’d love to talk about it—there’s a lot to unpack). All you really need to know for now is that Look Back ends the way all movies end: with the credits. As Ayumu sits alone at her desk and draws and draws and draws, the names of those who in turn drew her scroll across the screen. And watching those names, seeing this comparatively small production crew—equally as intimate as the contents of the film—recognized within their art…for me, that is the emotional peak of Look Back. That’s what the entire thing builds towards. Names like Ayumu’s and Kyomoto’s. Name’s like Fujimoto’s and Oshiyama’s. Names like yours and like mine.

I still have doubts and I still get jealous and I still struggle, struggle, struggle to write anything at all. I always will till the day I die. It’s probably time to accept that. And it won’t take long before I forget how Look Back made me feel, how inspired and energized it made me. It’s inevitable. It’s happened a thousand times before.

But that’s okay. It’s all just part of it.

Music of the Week: Hawaii Champroo by Makoto Kubota & The Sunset Gang

Fun fact: this collection of 70s pop rock (specifically New Music for the genreheads) taking heavy influence from Hawaiian and Okinawan folk comes from one of the founding members of the legendary noise rockers Les Rallizes Denudes. Not that you’d ever be able to guess, as this album is as breezy as they come. Sunshine island melodies operating in the same vein as what you might expect from Haruomi Hosono, the album also features a rendition of one of my favorite tracks, the classic Okinawan number, “Haisai Oji-san” among its collection of covers. Bust out your sandals and Hawaiian shirts for this one.

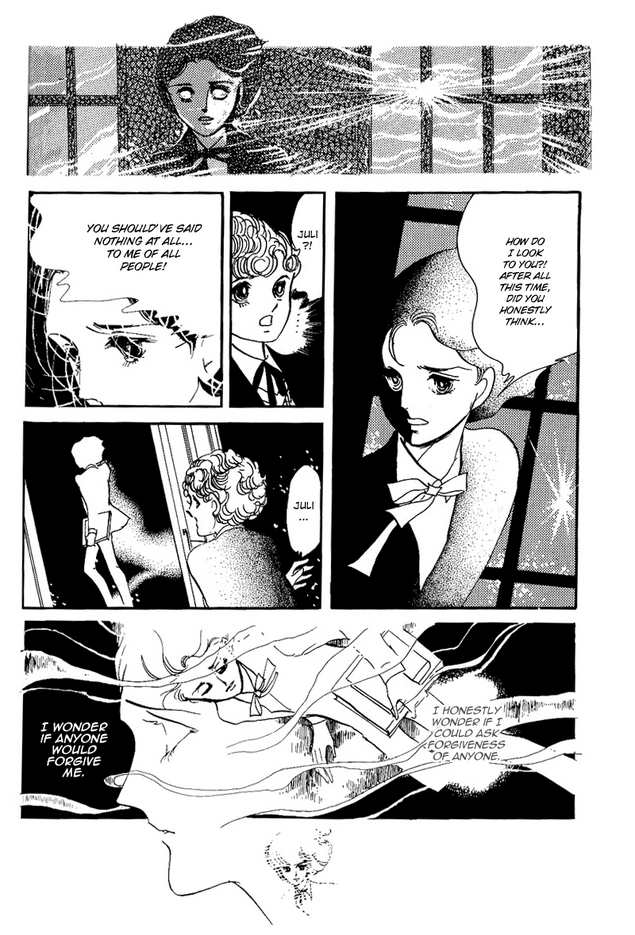

Book of the Week: The Heart of Thomas by Moto Hagio

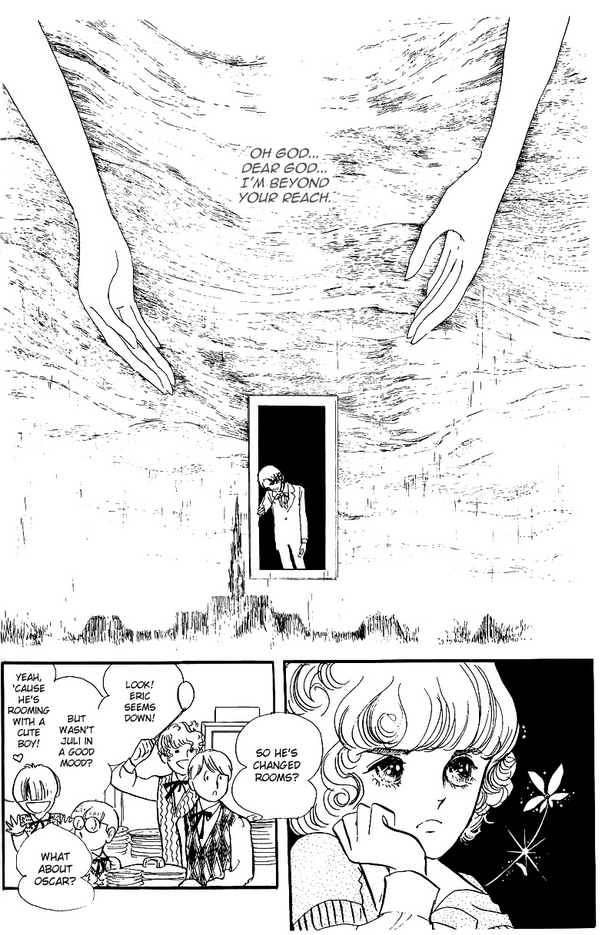

Name literally anything better than The Heart of Thomas (impossible challenge). This is the monolithic melodrama that solidified Moto Hagio as one of the greatest and most important manga artists in history, and it deserves its classic status and then some. About a boy at a boarding school haunted by a classmate who (might have?) committed suicide and named him in his suicide note, The Heart of Thomas is positively operatic, dealing in emotions so big that reality can’t contain them, visual metaphors frequently taking over as the whole story proceeds in a blurred flurry of overlapping images that even in form call to mind ghosts. Here, Hagio will draw the most devastating thing you’ve ever seen in a tiny little corner panel, and then you’ll turn the page and see a full spread that is the most devastating thing you’ve ever seen x20. Manga truly doesn’t get better.

Movie of the Week: A Forest with No Name (dir. Shinji Aoyama, 2002)

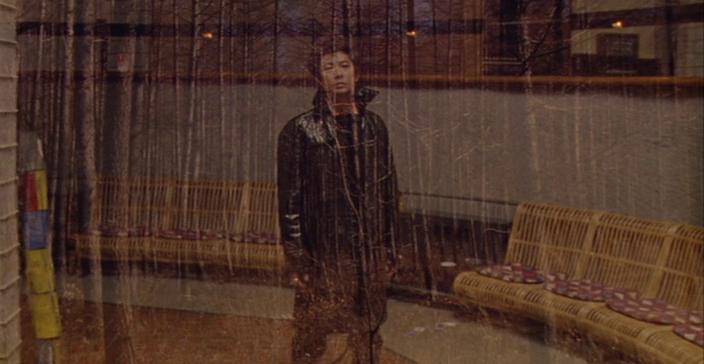

One episode of the Private Detective Mike series (that I might have to talk more about someday—it’s probably some of the best tv ever made) uncut and blown up for the big screen, A Forest With No Name sees director Shinji Aoyama embrace the influence of his mentor, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and craft a quick and hidden entry in brain-itch cinema. Following rough n tumble detective Mike Hama as he infiltrates an isolated cult, this movie is quiet and patient, taking its time to saw down your tethers to reality until they start snapping one by one. By the end you’ll feel brainwashed yourself and half-believe everything you thought you knew about the world is a lie. Chilling, confounding, and deserving of far more attention than it’s gotten.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here's an excellent article digging into Moto Hagio's work