Talking movies | River

Trying to make sense of time loops.

Time loops are everywhere. They’ve taken over our lives.

Intentionally or not, the idea of being trapped in a looping span of time has become an integral part of our modern storytelling, its forced narrative repetition inescapable no matter where you look. Even ignoring the stories literally about it—the games (Loop 8), the manga and anime (Summertime Rendering), the movies (Mondays)—the loop remains, escaped to a broader, metatextual level. Remakes and reboots dominate the media landscape, stories played out either exactly the same or coupled with an uncomfortable sense of déjà vu, while the rise of video games has meant the rise of checkpoints and game overs, of repeating the same actions and cutscenes over and over again.1

They are so present, even in those unnoticeable ways, that sometimes it can feel like we are all in a loop, too. Who knows. Maybe we are.

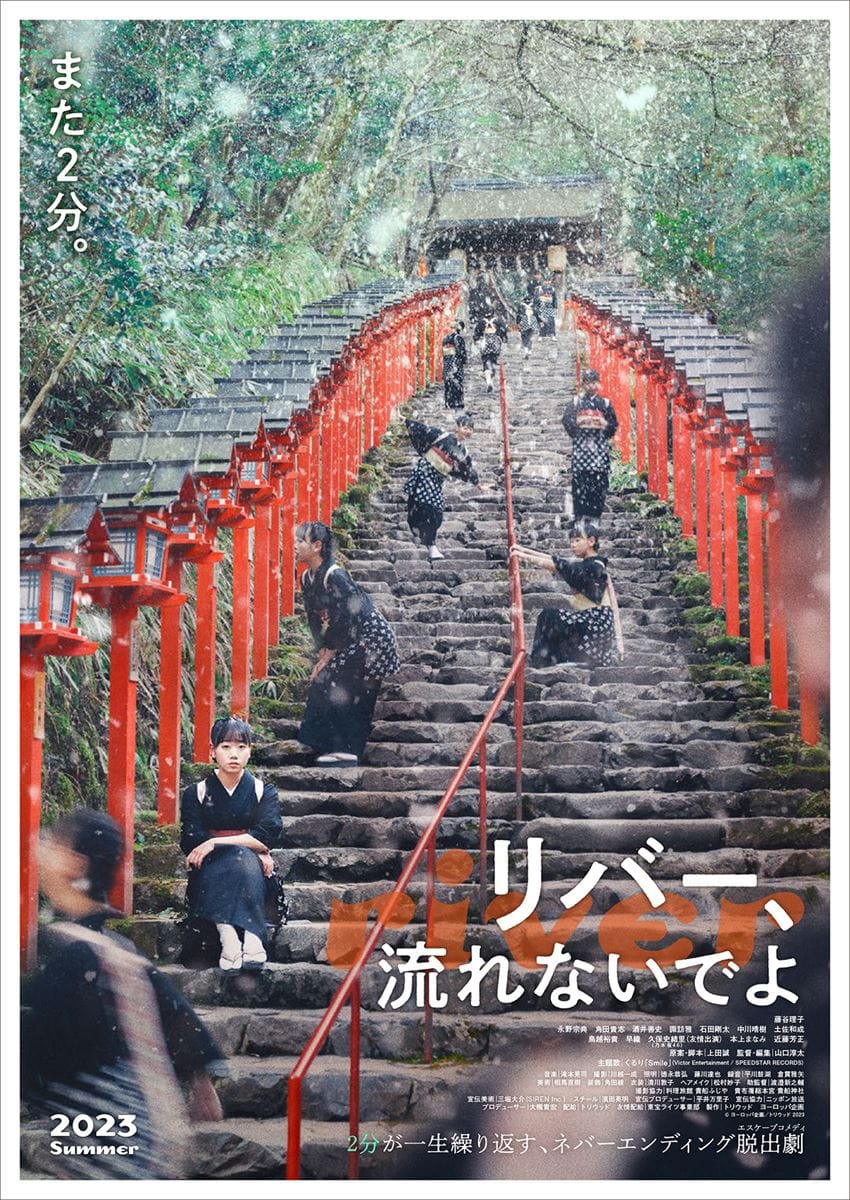

River, the latest film from director Junta Yamaguchi is, surprise surprise, yet another movie about a time loop. Set in a gorgeous inn location in the middle of nowhere beside a river, mountain, and shrine, the movie follows Mikoto (played by Riko Fujitani), a young staff worker in love with a cook as she, and everyone else at the inn, find themselves trapped in an endlessly repeating two minutes.

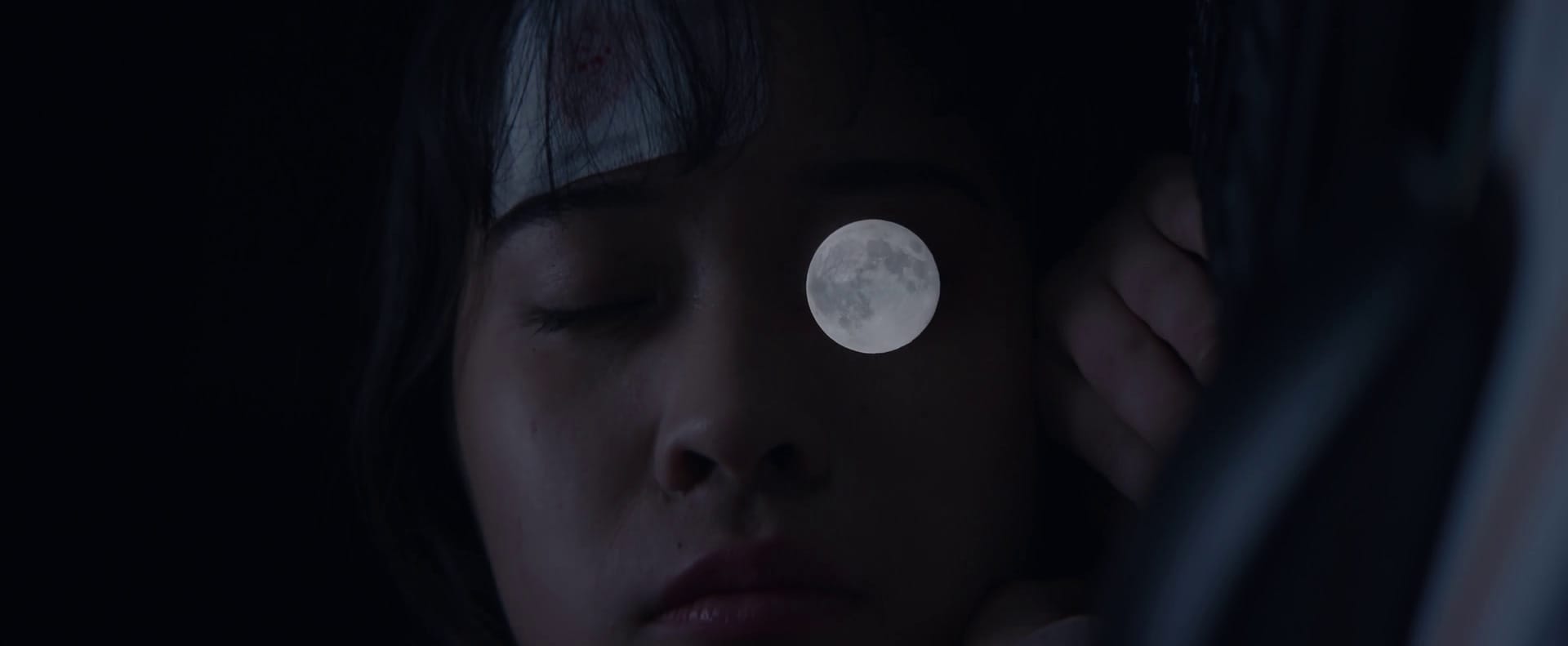

This short, two-minute loop is a holdover from Yamaguchi’s previous film, Beyond the Infinite Two Minutes, a movie which River also shares its light touch and gentle comedic sensibilities with. But whereas that film told its time travel trickery through an impressive ever-expanding one cut that felt like looking at a mirror in a mirror, River moves more internal, rigorously following Mikoto through this real time narrative, image only ever cutting at the end of each loop and always returning to her face at the moment it all begins again.

The result is something more layered and emotionally complex, one where Mikoto’s anxieties of missed chances and lost love become driving fuel for the genre mechanics at play. And it isn’t just her: everyone at the inn is suffering in a way that the loop solves. These are people being strangled by work exploitation, by creative expectation, by the weight of dreams; people who crave for time to stop and who want nothing more than their societal retreat to last forever.

The loop is happy to abide.

In Japanese media criticism there is a classification of story known as sekai-kei.2 Beginning on the internet as a way to criticize the glut of Neon Genesis Evangelion influenced otaku media hitting the market, sekai-kei stories are broadly accepted as ones where the delineation between the emotional conflict of the protagonist and the larger physical conflict affecting the world is erased. Think, for example, a post-apocalypse where the fate of the world depends literally on the main love interests getting together.

The term is largely used as a negative, stories fitting the sekai-kei mold seen on some level as anti-social wish-fulfillment in the wake of a collapsing economy and national tragedy; a sort of narrative actualization of the rise of the hikikomori (someone who completely isolates themselves in a single room for months to years on end). It’s so much more comforting, sekai-kei stories suggest, to live within oneself, to escape and ignore the influence and pressures of society, to believe that community does not have power.

This idea certainly applies to time loops—which are often considered a part of sekai-kei—and it certainly applies to the cast of River. You can see it clear as day in Mikoto, who over the course of the film begins to realize this might all be her fault, that time might have bent to her desires to allow her to live, if only briefly, in a lighter than air rom-com where life is interesting and exciting, and there aren’t any real conflicts.

And this is true on an even broader scale: River is an immensely likable movie, clever and laugh-out-loud funny without ever turning obnoxious or dipping into self-parody. The highlight of the film, a breathless series of two-minute dates as Mikoto and her love interest keep finding new ways to run away from their responsibilities, is almost criminally charming, the kind of scene that makes you wish it never had to end.

But things do end. You can’t run away forever. Time might loop, but it is never static; eventually things will break. As the story goes on, hatred bubbles and anxieties run loose within the inn as existential meaning collapses under those two minutes. Despite how fun it all is, River is not afraid to get serious and even scary as it transforms into an interrogation of its own genre, tearing into its escapist fantasy to critique these ideas of romantic societal withdrawal.

It all becomes crystal clear in the end, when things out of any one person’s control come to the front and the only way to fix it is to get up, put aside the daydreams, and work together to finally let time continue. It is a beautiful, surprising, smart and funny conclusion to a beautiful, surprising, smart and funny movie—one that is genuinely optimistic without being cloying or overly naïve.

River is, for my money, one of the cinematic highlights of 2023. Be kind, be together, kill the loop.

I can’t wait to rewatch it.

Music of the week: NYAI - OLD AGE SYSTEMATIC

An album I’ve etched into my soul. Power pop in the vein of The Pillows, full of the infinite melancholic potential of adolescence told through blarring hazy guitars, beautiful male/female call and responses, and some of the catchiest hooks in the biz. Anytime I need to remind myself why the world is beautiful and rules and the best thing there is, I come running to NYAI.

Movie of the week: Mondays

Forget Japan; when it comes to fun, there wasn’t much better for movies in 2022 in the entire world than Mondays, a ballistically entertaining low-budget time loop comedy that is paced like a dream, full of laughs, and boasts some genuinely exciting, surprising editing. What made one of the best movies of the year period though, is how it starts as a satire on the banality of work and slowly morphs into a beautiful and honest exploration of art, individuality, and the joy of collaboration. The kind of movie that makes you fall in love with movies all over again.

oh, and here’s an incredible dive into the history of a legendary anime studio

the rise of games has also seen the rise of a kind of checkpoint storytelling that takes advantage of this baked in repetition. Visual novels and adventure games especially have, for a long time, used replaying stories for profound thematic, emotional, and narrative effect. ↩

90% of my knowledge about sekai-kei comes from this very good thesis paper that if you have any interest in learning more you should absolutely read: “Sekai-kei as Existentialist Narrative: Positioning Xenosaga within the Genre Framework” ↩