Talking movies | Shadow of Fire

Examining the boom of post-war movies with Shinya Tsukamoto’s latest.

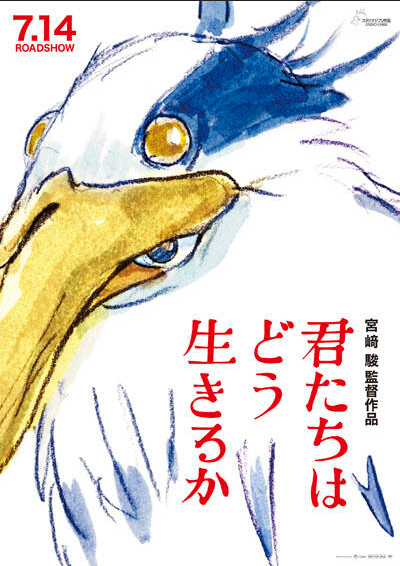

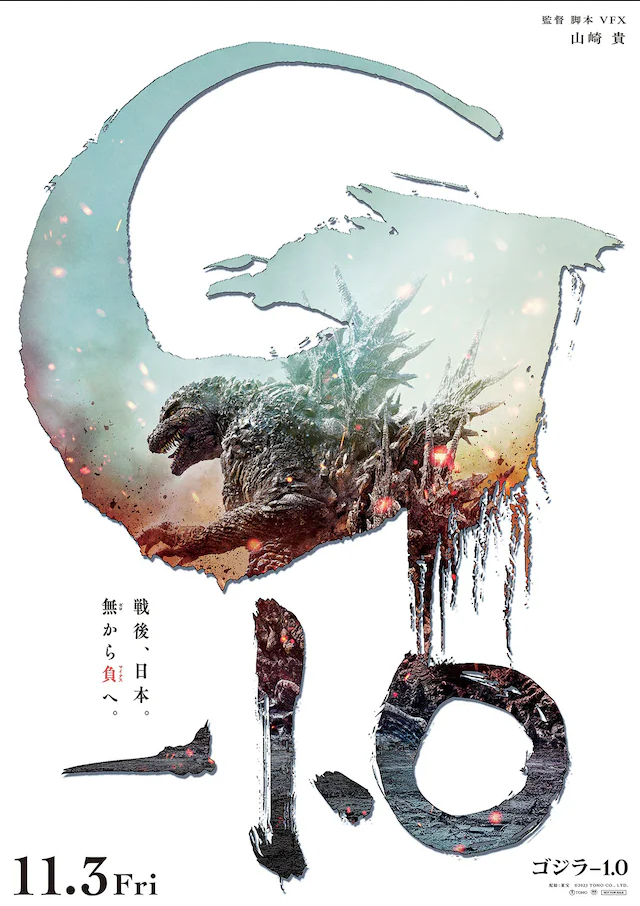

There is currently a noticeable boom of Japanese stories dealing with the lingering after-effects of war. 2023 saw Godzilla Minus One become a worldwide sensation by turning the monster into an allegory for post-war trauma; The Birth of Kitaro revealed an iconic anime and manga character as victim of lingering resentment in the face of World War 2; Totto-chan: The Little Girl at the Window moved autobiographical, recounting a child’s experiences with a non-traditional education system during the early 1940s; Till We Meet Again on the Lilly Hill used a time-travel romance with a kamikaze pilot to recognize the pain and scars that bedrock the world today; Hayao Miyazaki’s latest, The Boy and the Heron, filtered semi-autobiographical elements of his childhood around WWII into a grand and complex treatise on existence.

And the run hasn’t even stopped. Already, so early on into 2024, we’ve seen the blockbuster release of the live-action adaptation of the (fantastically fun) hit manga Golden Kamuy, detailing the cat-and-mouse struggle between soldiers of the Russo-Japanese war fighting to find some purpose to hold on to.

five of these are playing at my local theater right now

In all of these movies, through wildly different genre and tone and aims, a similar sentiment repeats.

“The war isn’t over.”

“My war hasn’t finished.”

“The real war starts now.”

It's become a motto, a refrain echoing through stories. The war is everywhere. It will never end.

Among this cluster is another film, one which deals even more directly with the fallout of World War 2 and what it means its descendants—to us.

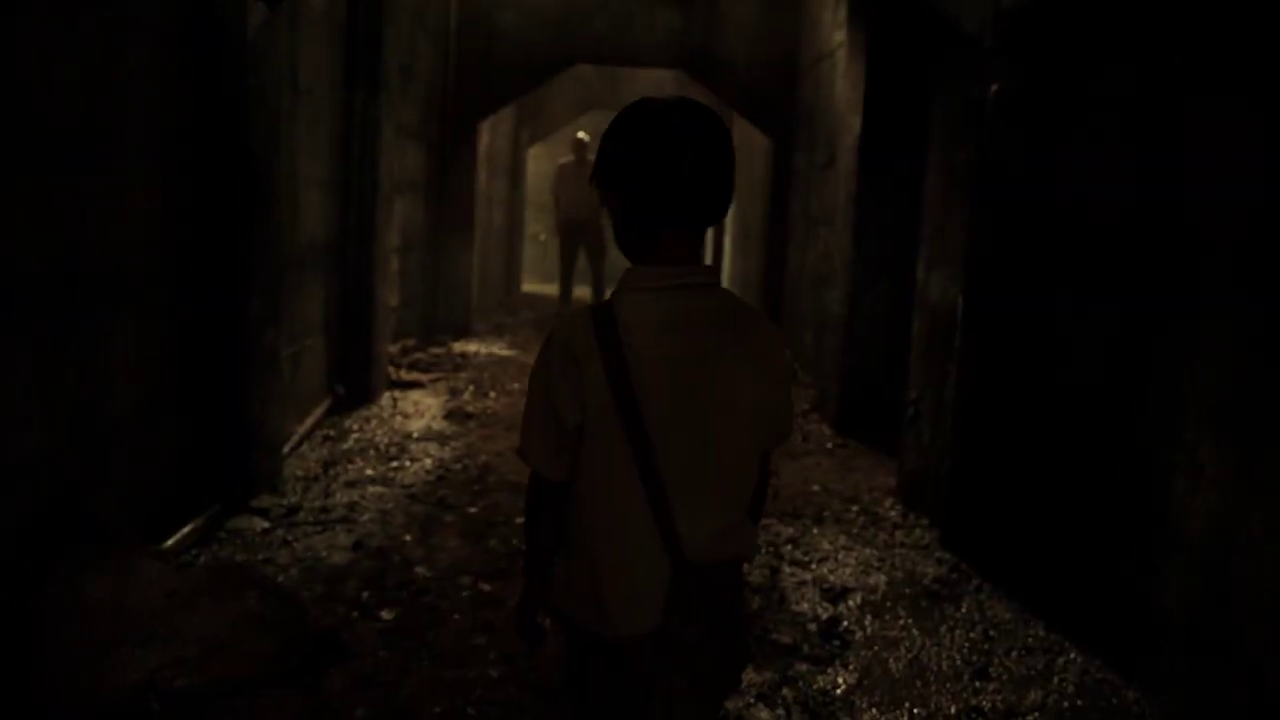

Shadow of Fire, directed by the legendary and hugely influential Shinya Tsukamoto, is the story of a child and a gun. Split broadly into two halves, it is a story that is small and condensed, streamlined to startling simplicity. Taking place immediately after World War 2 in a destroyed Tokyo of rubble and rust, the boy—abandoned and alone and carrying a gun in a bag—is taken in by a young woman begrudgingly turning to prostitution and a traumatized soldier. The boy leaves with a stranger looking for a man from his past. The boy returns. Credits roll. Dialogue is sparse and the runtime is short.

The image drawn up with Shinya Tsukamoto’s name will inevitably and forever primarily be one of grinding metal. His debut feature, Testuo: The Iron Man, is a towering cult classic that helped usher in an era of down and dirty punk filmmaking with its low-budget and unhinged cyberpunk energy. That he’s made two sequels to that movie as film as well as various horror films, and has attached himself—via acting or otherwise—to works such as the classic subterranean nightmare Marebito, has ensured it: he is a director of concrete and wire, of steel and blood.

It's obvious why, but it’s also a shame. Tsukamoto has always had a career of full narrative, thematic, and tonal variance, and post-2010 his style has only drifted further and further into something entirely new. Shadow of Fire highlights this perfectly, a sort of capstone on his current interests.

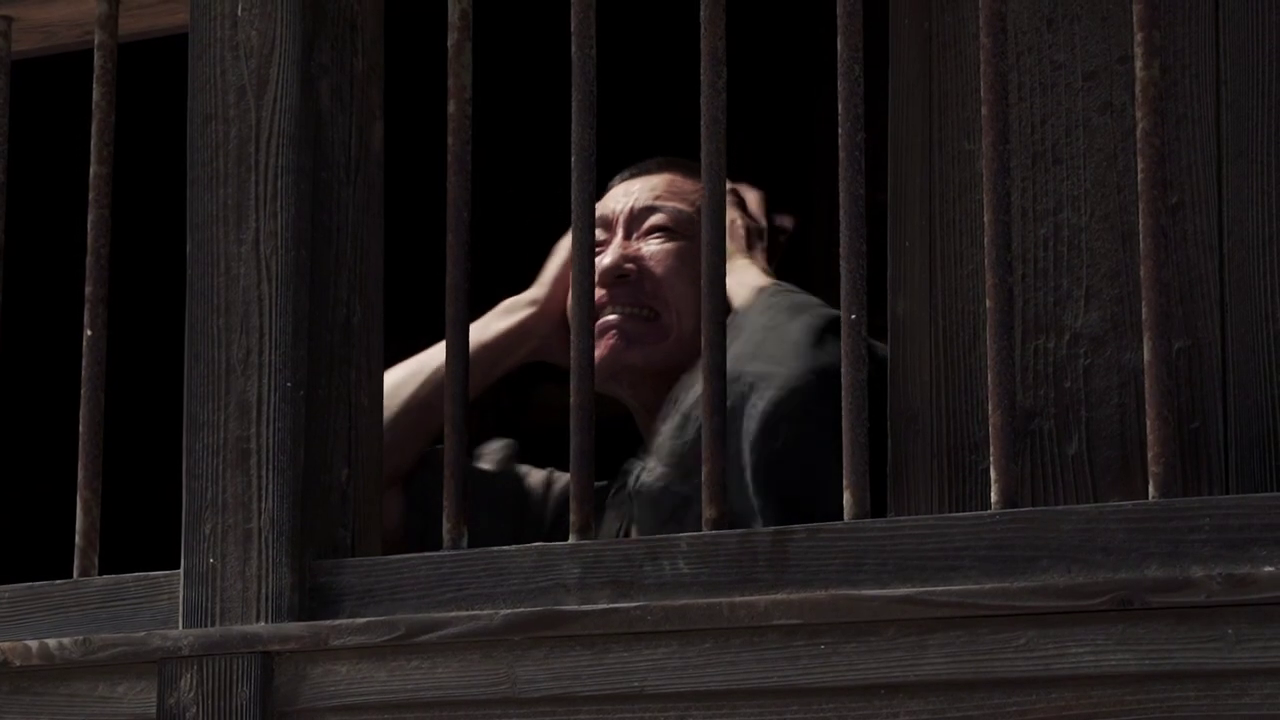

Shadow of Fire is a harsh film. Tsukamoto shows no interest in romanticizing the path of healing. Life after war is not pretty, it’s not clean, the road is not paved or straight. There might not even be a road at all. When the soldier living with the boy and the woman hears gunshots, he snaps. He cowers and whimpers and becomes violent and tries to kill the only people he has left to love. But there’s no metaphorical monster waiting to be defeated that will fix things, there is not the chance of flying to another time or another world. He doesn’t get better. At the end of the film the boy finds him again, sitting in an alley with other soldiers, all of them ruined beyond repair, barely able eat. Nobody has a name anymore. Nobody has a past that isn’t connected to all the killing. Tsukamoto understands the truth: we have collectively broken all of us.

You can see it in the way the movie looks. Filmed with aggressive digital photography and primarily kept tight in small locations—a large amount taking place in the woman’s home—everything moves with a sense of reality a half-step out of sync with what it should be. It’s all destabilized. Frequently, the camera will drift away to stare at rusted walls or scratched up floors so close that they become abstracted, nightmare noise. In perhaps the most startling moment of the film, those same scars that line the home literally become Japan itself, stains becoming wiped out buildings, an endless expanse of destruction. Our architecture, the landscape of the entire country, has become a reminder of pain.

The man the boy leaves with is on a quest for revenge. He is searching for his commander in the war, the person who ordered his friends to death, the person who allowed his comrades to lose arms and legs and eyes and ears, to kill and be killed in empty, pointless sacrifice for “country”. When the boy leaves him, standing over the body of his commander filled with bullets, he sees the man reach up to the moon. When he returns home, the woman is dying.

So why is it that these films have started to emerge now of all times? Why has the war returned?

While filming Shadow of Fire, another war broke out, though calling it a war is too generous. It’s a genocide. Ukraine already burning, Somalia already burning, Syria already burning wasn’t enough. Now we are forced to also see Palestine suffer. Turn on the TV or go online and all you can see is the image of children crying, children alone, children dead. Their corpses line streets, dangle from stairwells and rooftops. Any adult still breathing is good as dead too, souls empty and broken, cradling their children covered in their blood. They sob and stare and hold themselves and others and beg to not wash their hands or their faces, to not get rid of the blood.

The world is filled with the child from Shadow of Fire. He is everywhere you look, flooding our streets and overflowing our homes. Godzilla was a born as a reaction to the bomb. Gegege no Kitaro was born in its aftermath by an armless soldier who saw Japan as a land of ghosts. The Boy and the Heron was born from memories of a childhood in the wake of destruction. The creators of these stories are all old now or dead now, grasping towards the end, filled with more experience and knowledge and stories than any of us could possibly imagine. They are all still children, as young as any of us.

Wars are fought by adults, but nobody in a war ever is one.

Why do we make these stories? Because kids are still dying. Because the scar bleeds more than ever.

Music of the Week: Kakkoi Koto wa Nante Kakkowaruindaro by Yoshio Hayakawa

The album following the dissolution of the Jacks, a hugely influential rock band Hayakawa was part of, is a classic in sadsack folk. Haunted and lonely even when he's singing songs about the NHK (Japan's national broadcasting company), this is an album for late nights wandering a run down city. Listening to this while driving past graves, factories billowing smog in the background, send my mind into all sorts of places. The track "Muyou no Suke" (無用の介) especially had my jaw on the floor, its echoing piano and hissing-noise-as-drums...wow!

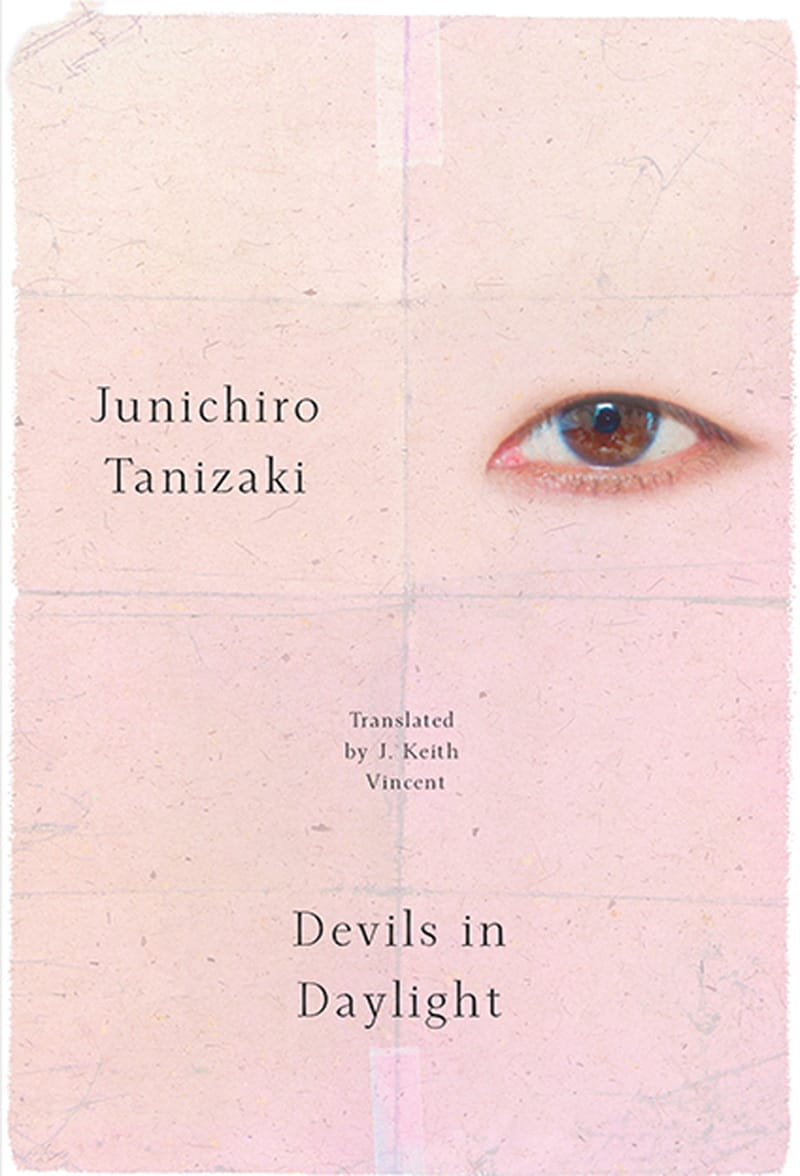

Book of the Week: Devils in Daylight by Junichiro Tanizaki

My number one favorite mystery comes from one of the kings of the strange (he was an influence on Edogawa Rampo if that tells you anything) and what a story it is. A bizarre, perverse, meta-textual maze that starts with silent cinema and the cypher from Edgar Allen Poe's short story "The Gold-Bug" before plunging into questions between viewing and participating, art and life. Plays and twists itself in ways that still read every inch as surprising and shocking as they must have nearly 100 years ago. Feels like some sort of Rosetta Stone for my interests.

Movie of the Week: Children of the Beehive (dir. Hiroshi Shimizu, 1948)

This all-timer follows a soldier fresh from the battlelines who ends up traveling Japan with a group of war orphans and is, despite the premise, as sweet and gentle and warm as movies come. A found family navigating tragedy with humor and kindness, the movie is a big-hearted celebration of the goodness you can find in others. Until it suddenly isn't and reality comes crashing down. An absolute masterpiece of post-war filmmaking from a director who walked the walk--not only are the children real war orphans, but he set up his own orphanage for them--that manages to be hopeful without being naive.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here's an interview with the translators for the recently released Linda Cube patch (!)