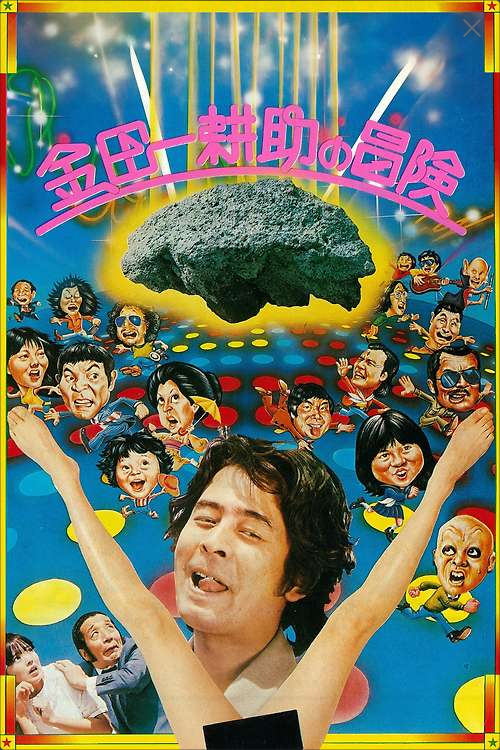

Talking movies | The Adventures of Kosuke Kindaichi

Rebuild of Kindaichi 3.0+1.0 Thrice Upon a Crime

"Goodbye, Mr. Todoroki. Goodbye, Kosuke Kindaichi. Goodbye, everyone."

Watching The Adventures of Kindaichi Kosuke is to drown yourself. A hyper-dense post-modern comedy from Japan’s greatest maximalist, Nobuhiko Obayashi, every shot is bursting with detail, references and allusions, background gags and cameos. It is a veritable pop culture extravaganza, rushing manically from joke to joke, reference to reference. A dream of Maxim Coffee funnels into an animated Superman flying across the screen only to land directly into a playful parody of Toho’s 1971 film Lake of Dracula. It presents a world taken over by media, where people and history and place exist only in relation to the art all around them, constantly exploding like fireworks. The movie never slows its pace, never gives a moment of rest from the chaos. You can only sit and suffocate, gasping for air that will never come.

Maybe that’s why it’s so comfortable. We’re all always drowning after all.

The rapid acceleration of art as commodity is impossible not to notice. We all feel it. It has passed the breaking point years ago, train flying over a cliff with no rails, propelled by speed alone. A million shows and movies and stories are produced each year by a million splintered streaming platforms consuming and excreting each other ad infinitum, all owned by only a handful of companies. People like Star Wars? Here’s ten Star Wars TV shows at once. Gee, the Marvel Cinematic Universe sure is doing well, what if everyone had one? Meanwhile, writers and animators and actors are paid peanuts for criminal overtime while executives and Silicon Valley techbros hail AI as the “democratization of art” in a thinly veiled effort to turn it all into a perpetual motion machine of capitalist sludge.1

We don’t watch movies anymore. We don’t read books or play games or listen to music. It’s all just “content” now, and we consume it. We welcome the water as it rises above our heads.

I’m no different. I’m the worst of the worst, sunk down deep where light won’t reach with concrete on my legs. I mean, look at me—I’m constantly writing about the stuff. A large part of my identity is, like it or not, inexorably wrapped up with fiction and media.

Kindaichi isn’t any different either. In the film, the detective—who began life in a series of deeply intelligent mystery novels by author Seishi Yokomizu from 1946 up through the ‘70s—exists both as character and person, trapped in this prison of pop culture. The Kindaichi books exist in the film, as do his previous filmed adaptations. But Kindaichi himself exists only through what he has inspired. He is desperate for murder and crime because, if there is none, then there can be no stories, and if there are no stories, then he has no reason to exist. He, like all characters, exists entirely within his relation to media. If that’s the case, then we are all characters, too.

Enter a gang of masked, brightly colored roller-blading art thieves who send Kindaichi on a sprawling journey to find the missing head of a sculpture and in turn solve a Kindaichi short story that was never finished. What follows is an infinite stream of gags—in terms of zaniness and joke density think something like Airplane!—Kindaichi fumbling through a dense, near incomprehensible web of parody on top of parody in search not just for art, but for himself.

He needs this. He needs crime and murder and the depraved, and so do we, though we try so hard to say otherwise. We love true crime; we invent villains to capture. Everything has to be a story.

What’s difficult about all this is that almost everything is a story. So much of human experience is defined and filtered through stories. There are the stories we read and watch, of course, but there are also the ones we tell—the stories about how our day went, what our co-worker ate for breakfast. History and the news are inevitably stories, reality reflected once or twice removed so that it is similar to truth but also something completely different. Kindaichi is a detective. He is in search of the truth. What does he do if there is no truth to find?

The answer is in the ending. After two hours of exhausting mayhem, the movie breaks. The world breaks. As studio staff laugh at plot holes and pick at flaws of the movie that is still playing, Kindaichi sits down in an expanse of white and begins to talk.

He talks about crime. He talks about Japan. He talks about his role as a detective—the storyteller of a crime—and how cases propagate and connect and “take on a life of their own.” Reality, he suggests, is not satisfying like a story; it isn’t clean. Only the world of crime, of fiction and story, can provide real, clear meaning to a life.2

“What’s the fuss?” someone asks. “You’re making money.”

He needs his stories. Like all of us, he’s nothing without them. At one point Seishi Yokomizu, the creator of Kindaichi, makes a cameo and receives suitcases full of money for the film. He turns away and mutters, face old and tired, “I never wanted to be in this movie.” He accepts the money all the same.

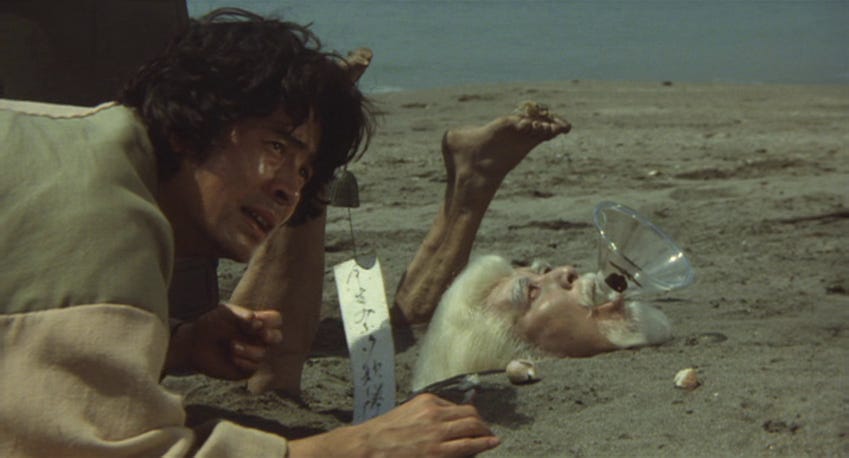

Kindaichi, like Yokomizu, doesn’t have a choice, not really. It is all already too far gone. He starts making his stories himself. Inspector Todoroki, Kindaichi’s closest friend, finds him on the beach, organizing a dismembered corpse in the sand into an incomprehensible art piece. Todoroki raises his gun and aims it at the god of his world. He pulls the trigger.

Kindaichi is dead. He will never be allowed to die.

The Adventures of Kindaichi Kosuke is a movie about drowning, about the suffocation we are all experiencing as characters in stories made up of nothing but other stories. Can we escape? Can we ever find land again? And if we ever do swim our way out and break through the waves to the surface, what then? Will we know how to breathe the air? Or, so used to the water, will it too drown us?3

Music of the week: Super Ball - Super Ball EP

Like music by people who have never heard a song in their life; nine minutes of tunes sliding off the body to the floor like the notes are parts of a Dali painting. Jandek, but instead of some mysterious dude ripped from a Lynch movie living in Texas it’s three Japanese high school girls. A total classic of outsider music weirdness.

Movie of the week: Twilights

If the high-energy experimentation of early Nobuhiko Obayashi had a child with the avant-garde symbolism of Shuji Terayama, this would be it. And a what a precocious, joyous kid it is. 30 breathless minutes of the most playful editing and camera trickery you’ll see, used for a surprisingly sweet, affecting story. The final five(ish) minute tracking shot especially is something I come back to constantly. One of my all-time favs!

oh, and here’s basically my favorite vid in the universe

I cut out a bit about how the internet is exactly the same, but let’s be clear: the internet is exactly the same. A real rotting carcass of consumption never allowed to die by the three companies that own it all. Boy howdy do I sound bitter on this one. ↩

A couple weeks ago I wrote about Kindaichi Kosuke’s only rival to the title of Japan’s greatest detective, Akechi Kogoro. Highly recommend reading that too, which ties in very well with another aspect of Kindaichi’s speech. ↩

Look, I know how I made it sound, but the movie is funny. Totally off the wall goober cinema; perfect viewing with weirdo goober friends. Don’t be put off thinking it isn’t dummy watchable! ↩