Talking movies - The Man Who Stole the Sun

Welcome to the a-bomb corner, what is your desire?

Before we get into this week: I had a guest post in the most recent Read Only Memo where I rambled briefly about an old PC-98 RPG Maker game! So thankful and jazzed for the opportunity, so go check it out and then subscribe to ROM (it’s the best!)

When he was in the third grade, Kazuhiko Hasegawa searched for the news. It was usually right there, evening newspaper laid out in waiting when he came home from school. But this day was different. This day, the paper was missing; this day, there was nobody else home but him. So he searched. He searched and he searched and when he found it, he knew that he was going to die.

We've been rotting for a long time. Who knows when it started. Maybe it was with the invention of the internet, or with World War II or the industrial revolution. Maybe it started a hundred years ago, or two hundred, or five. Or maybe it's been happening since the very beginning, before tools and before language, when we all lived in caves afraid of our own shadows. Maybe the story of humanity is nothing more than a story of decay.

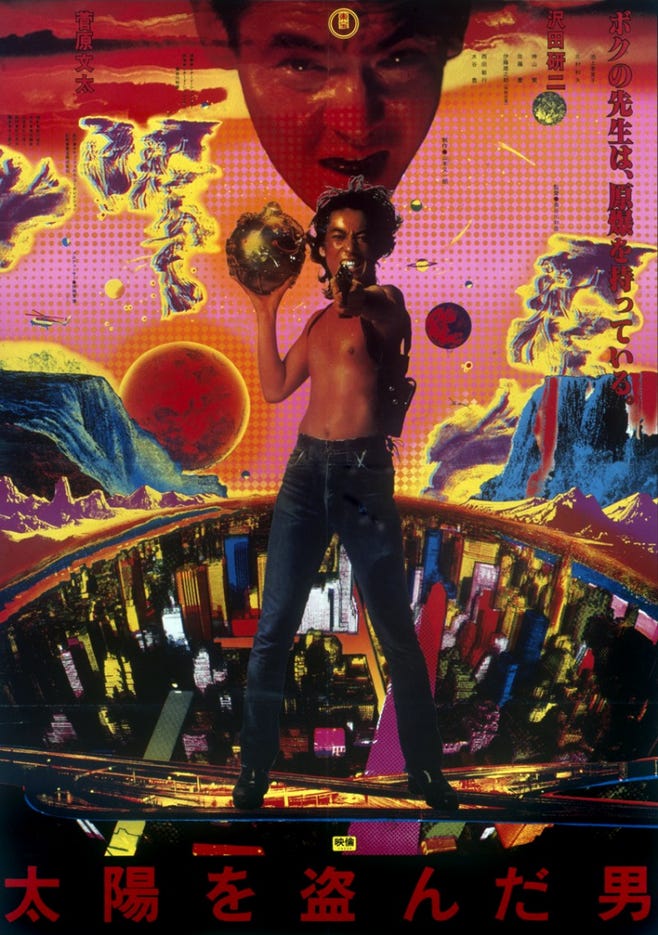

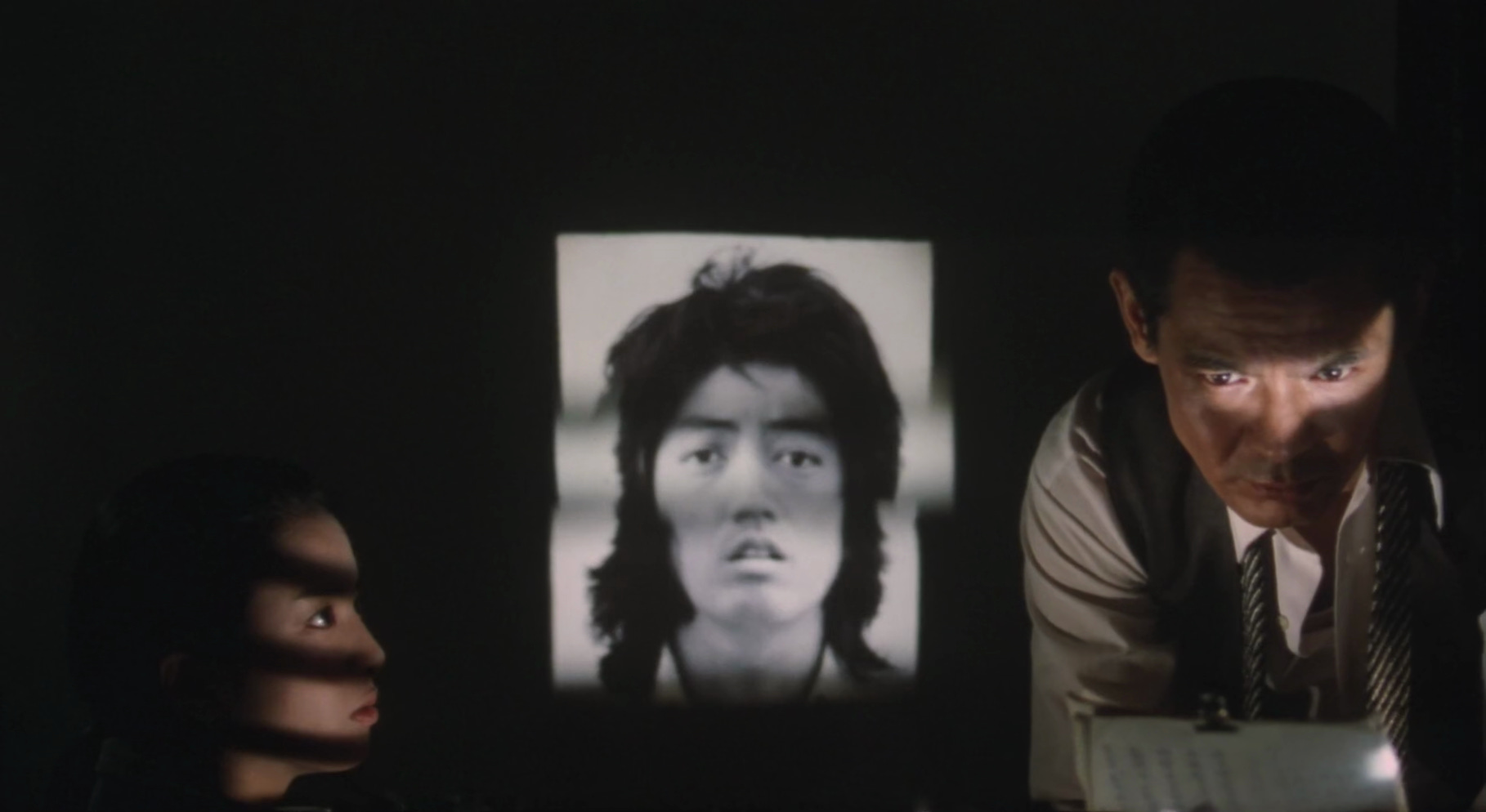

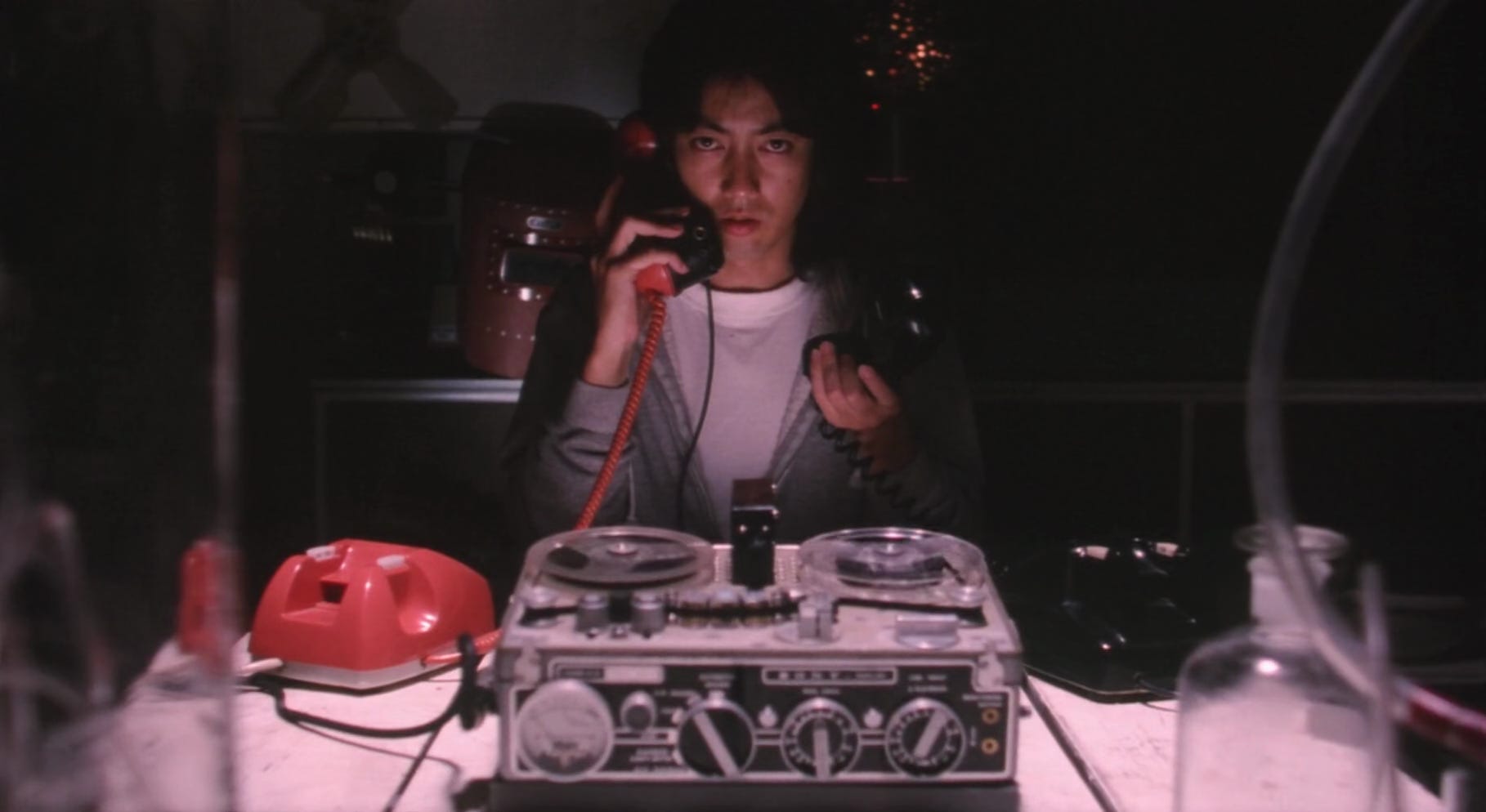

The Man Who Stole the Sun, a 1979 nihilist explosion of punk anger and unease, is a film dripping in our rot. Following a sleepy and disenfranchised middle school science teacher named Makoto who decides to make his own homemade atomic bomb, the movie manically dashes through an increasingly unpredictable string of events, flipping tone and style at the drop of a hat. In one moment, it is a lighthearted school comedy, in the next a tense hostage thriller; blink and it transforms yet again as the teacher robs a nuclear plant, the building taking on the design of a far-flung sci-fi film, action shown through a montage of still images. It can all feel rough, desperate; a movie in a mad, pathetic dash for life.1

That’s exactly what it is.

The news Kazuhiko Hasegawa found, hidden deep in a closet so he wouldn't find it, was about a boy. They were just like him in every way: born the same year—1946—in the same prefecture—Hiroshima—both exposed to the fallout of the bomb in utero. The only difference was that the boy in the paper was dead. Leukemia had taken him, linked to his radiation exposure that he had no say in, that the world forced upon him. Hasegawa saw this and he knew that death was coming for him next, that he was nothing more than a walking corpse. He was ten years old.2

It starts with the hair, once long and flowing, now coming out in great big clumps. Then comes the dizziness and the exhaustion, landscapes swaying, body propped up against buildings so as not to fall. Then it is in the teeth, blood oozing from gums, smile turned red. It doesn’t take long for it to become clear: by making the bomb, Makoto is committing a slow suicide. Even if the police never catch him, don't shoot him down in a rain of bullets, the radiation has already filled his body; he is already a corpse. He and the film’s director, a grown Hasegawa, have become one and the same, a reflection of each other. That’s just as well to him, though. At least now he isn’t asleep.

Or is he? Once the protagonist successfully makes the bomb, Japanese government and police under his control, the only thing he wants is to see a baseball game through to the end on TV. When asked over a radio show what they would do if they had an atomic bomb of their own, the film includes real answers from real people on the streets of Tokyo. They say they’d take days off work or demand better pay; they’d demand to see the Rolling Stones live. His answer and their answer are so small, so simple, almost childish in their lack of political motivation or concern for wider change in the world.

But why shouldn’t they be? Why shouldn’t they indulge in media, enjoy a baseball game, a concert, a vapid radio show? It’s certainly a better answer than the one those in power give: use the bomb for destruction and control, oppression and power. Compared to that, seeing the Rolling Stones is the only answer that makes any sense. In a world that feels hollow and without meaning, a wasteland marching towards death through conservative, capitalist ideology decided on by faceless individuals wholly removed from reality, the average person left stranded and powerless, a concert feels like the only moral thing to do. Pop culture, a long since dominate force in our lives, both defines and is defined by the society it hangs heavy over. It’s a mirror, a reflection of us. So bring us the band that celebrates sex and drugs. Bring us the band that hates The Man.

Makoto listens to the people and demands the Stones, and in all but a second, he becomes legend. The people of Japan start celebrating him and the bomb, a new folk hero who sees society the way society sees itself: rotting and dying. Let the ties loosen, let the people live. Otherwise, it might be better to just let the bomb go off.

And so, just as the protagonist uses pop culture—here the Rolling Stones—as a force and symbol of revolutionary empowerment and the discontent of the people, so too does Hasegawa, making a movie with the power to wake us all up. The reflections continue.

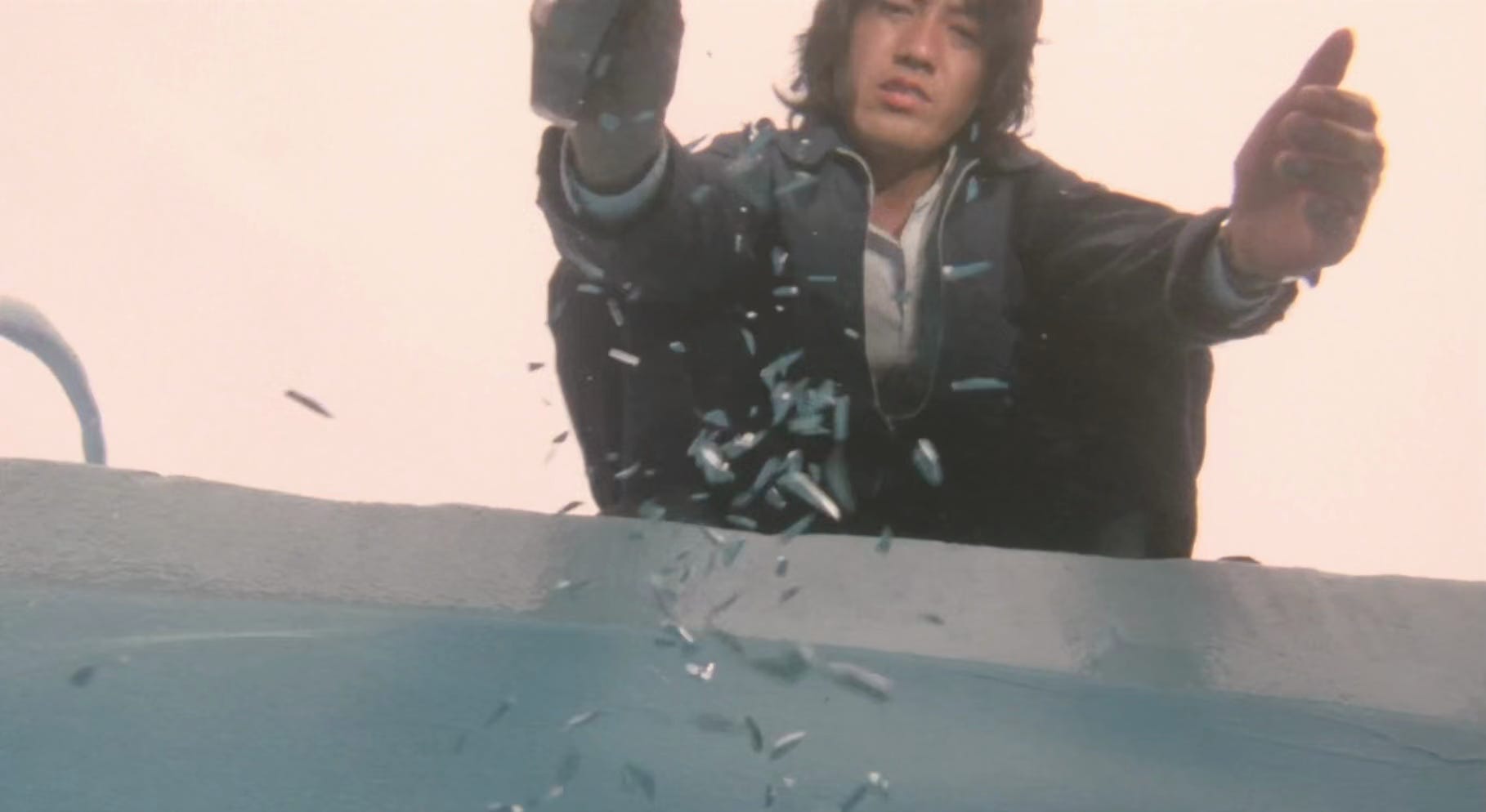

Production of The Man Who Stole the Sun is very nearly the story of the film itself, fiction becoming reality as Hasegawa and crew broke laws at every turn in a game of cat-and-mouse with authority, film and camera like a bomb that proves life. They would block highway traffic with no permit for a chase scene, sneak into the national parliament building with a fake bomb, rush a bus towards the emperor's palace. In one now legendary moment, counterfeit bills were scattered by the thousands from the top of a department store without approval, a young Kiyoshi Kurosawa (now considered one of Japan's great contemporary directors) chosen as the fall guy to be arrested for the sake of a single shot. Through Makoto’s journey towards death, the entire crew found ecstatic, dangerous life.

The Man Who Stole the Sun exists in reflections on reflections--life imitating art imitating life imitating. Hasegawa is alive. The film is alive. The protagonist, alive. And all of it, everything, is electric and dangerous, fighting tooth and nail for purpose and meaning even if it means death, even if it means the destruction of the entire world. There’s no other way to prove that the heart still beats.

Near the end of the film, the radio announcer who asked the country what they’d do with an atomic bomb is killed. She knows Makoto is sick, that the bomb is eating him up from the inside, that his body is rotting along with this rotting world. She knows all of this and looks at this dying man and tells him, putting the mask of a monster over his face, to “live a long life.”

When he was in the third grade, Kazuhiko Hasegawa searched for the news. When he found it, he knew he was going to die.

He never did.3

Music of the week: Ignition Block M - Houses of Fire

Self-described "Black Flag + Post-Punk + Theatrical goth female vocals" group gives you exactly that—a rush of lurching graveyard insanity with a singer who sounds like they are trying (and succeeding) to raise the dead, zombies emerging from the earth to dance. Perfect example of a band you just know is 100x cooler than you’ll ever be.

Movie of the week: Typhoon Club

A difficult, harrowing, literary and impossibly dense descent of a group of students trapped in school as a typhoon rages, unmoored from society and reality.

Almost aggressive in its refusal of easy, satisfying conclusions and filled to the brim with elusive symbols and allusions, Typhoon Club captures the true emotional sensation of a storm better than anything ever has, leaving the mind swimming at what it all means. The answer? It means everything. Genuinely one of my favorite films of all time, regardless of country.4

Thanks for visiting! If you liked what you read, share it around! It’d make my day :)

oh, and here’s a super fun vid about 2D PS1 games

This wild narrative is thanks to an out-of-control script from Leonard Schrader, brother to legendary screenwriter/director Paul Schrader who made one heck of a name for himself as a writer in Japan. ↩

P.S. The movie, with its almost apocalyptic sense of a 70s Japan crumbling as it is ruled by media, would make a very good double feature with The Adventures of Kindaichi Kosuke from the same year, I movie I talked about previously. ↩

Director Shinji Somai was actually an assistant director on The Man Who Stole the Sun! ↩