Talking movies - The many adaptations of House

The history of a cult classic that isn't just a movie.

It should have been the perfect start to Mitsuru Miura’s career. In 1971, while still a second year in high school, he wrote a single chapter manga titled “Yonimo Fukou na Otoko no Hanashi”. He’d been submitting work to contests and publishers for months by that point, feverishly chasing the dream he’d had since he was nine—becoming a manga artist. But nothing he did seemed to break through. He submitted and submitted, but every time failed to get results. And after an especially crushing loss—where he made it to the finals in a contest hosted by the prestigious Shounen Sunday only to lose at the one moment that really matters—his confidence was shaken. Could he really be a manga artist? Did he really have what it takes?

That’s when it happened.

“Yonimo Fukou na Otoko no Hanashi” was going to be published. And not just published, it was going to be published in Weekly Shounen Jump, now considered the defining manga magazine. In a single second, he had done what people twice his age could only wish for. In a single second, he was posed to become a major name in the industry he so longed for.

It would be ten years before it happened.

Due to family circumstances, after high school Miura entered the workforce, working in production for a furniture company. The job itself wasn’t awful, but it was exhausting, consuming. He hardly had time for manga anymore and it ate him up inside.

So, unable to bear the creative emptiness growing within him,f he quit. Leaving financial security, he took a small part-time job and dedicated his every free moment to manga. But it was like nothing had changed. His work still wasn’t getting picked up. When his mother found out what he did, she said he was dead to her. He continued all the same.

Over the next several years, Miura would join Tezuka Productions as an assistant to the godfather of manga himself, Osamu Tezuka, and slowly hone his craft to a razor point. Finally, after years of struggle, he began to get regularly published, one-shot stories cropping up now and then in various magazines. Finally, though dreams of serialization still eluded him, he began to his footing in the only job he could ever bear.

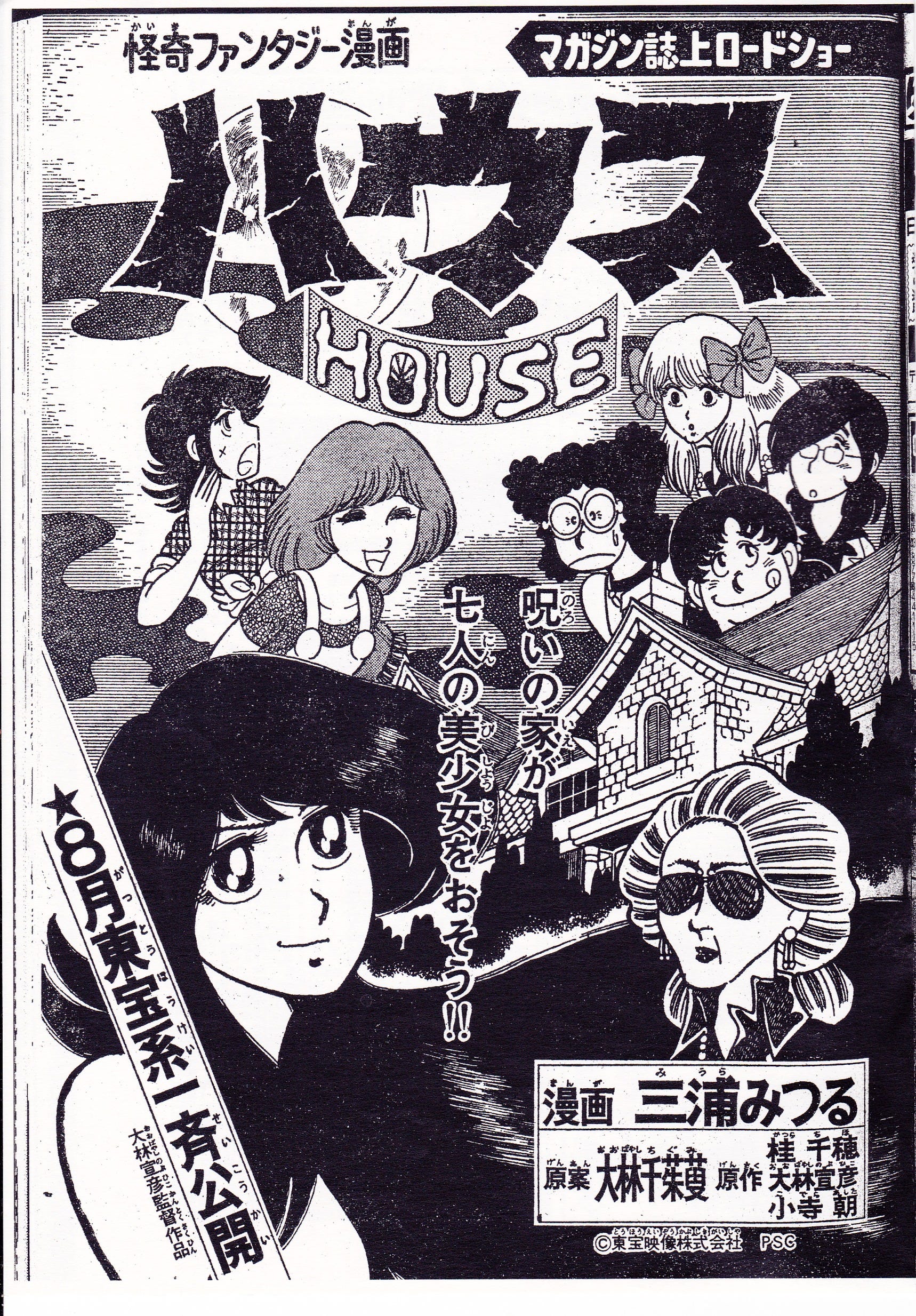

It was during this time, in 1977, as Miura was beginning to make a name for himself, that he was approached with an offer to make a twenty-page adaptation of an upcoming movie. Of course, he accepted.

The movie’s title was House, and Miura had no way of knowing the world of madness he was about to step into.

—

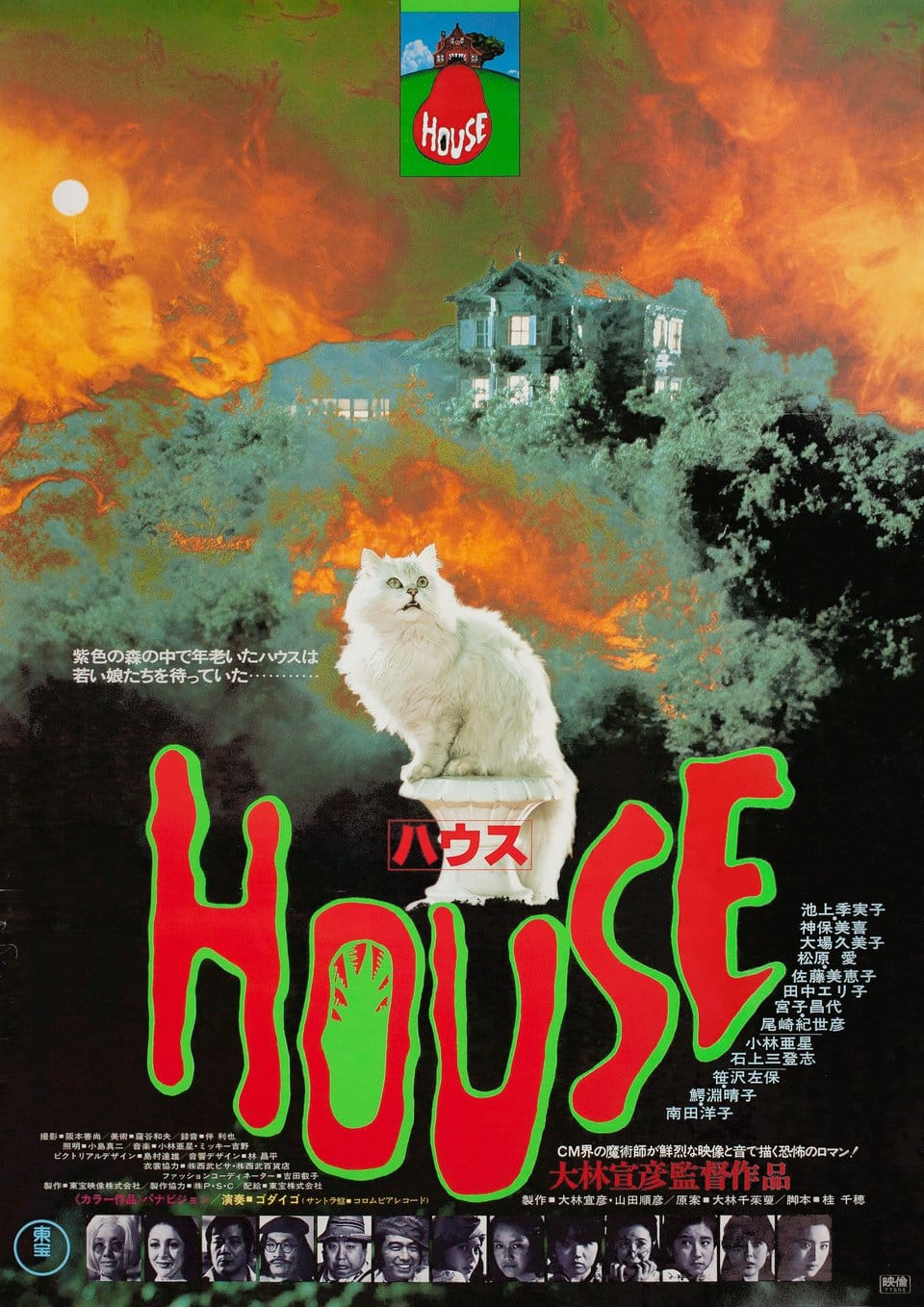

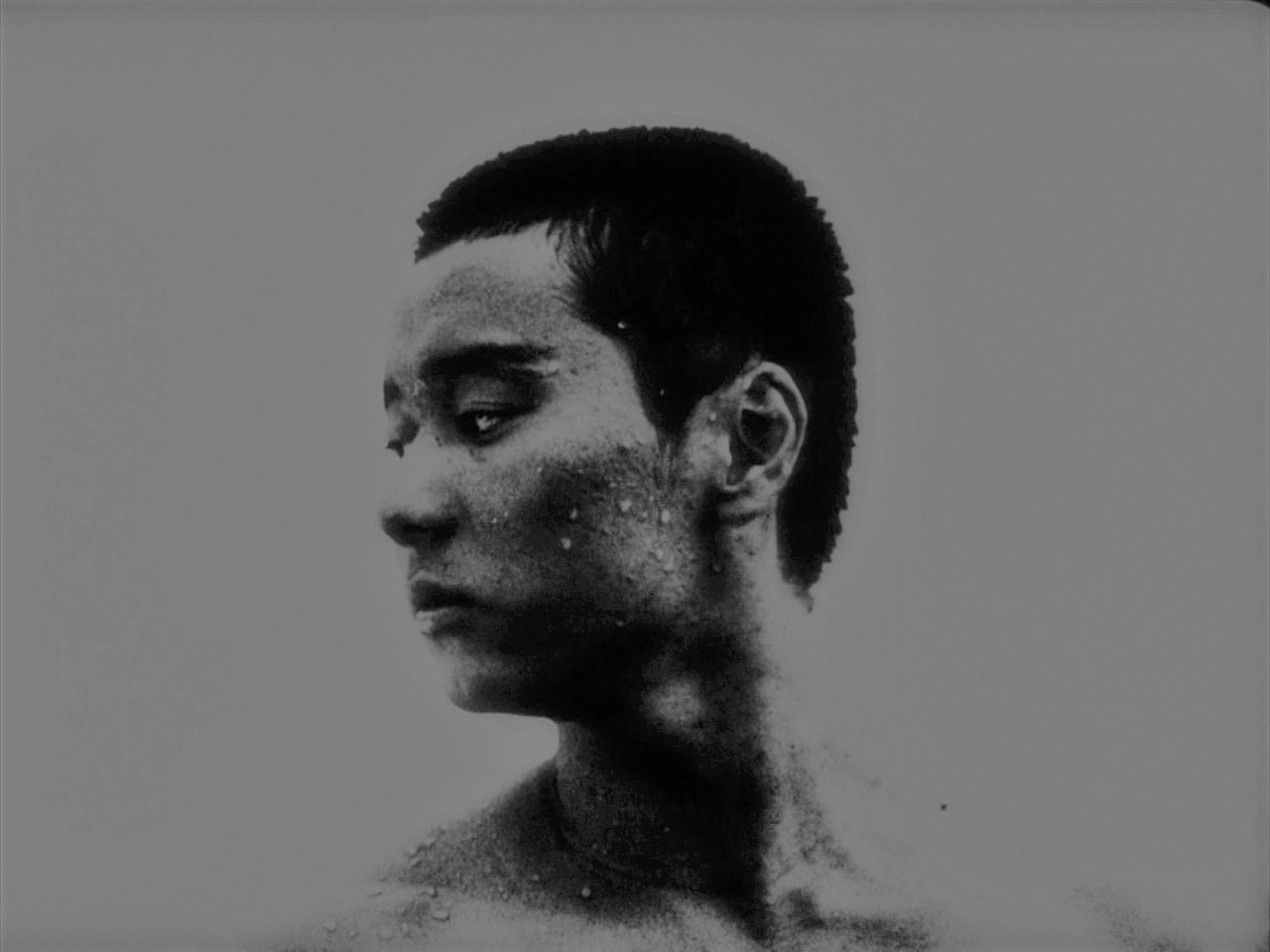

There’s so much and so little to say any more about House, the electrifying 1977 commercial film debut of director Nobuhiko Obayashi. A hit at the time of its release in Japan, post-2010s the film slowly (and then very quickly) gained a rabid fanbase worldwide, cementing it as a towering, Mount Rushmore member of cult cinema. And I mean, it’s obvious why: following a group of seven girls all named after their single character trait—like Beauty and Brains and Melody and of course Kung-Fu—who find themselves trapped in a madhouse haunted mansion, the film is an absolute ballistic work of imagination, every single shot the most densely packed “what is even happening” thing you’ve ever seen. One second a skeleton is doing the boogie-woogie, the next a piano is eating a lady, and then suddenly a painting of a cat is spewing metric tons of blood and some poor sap turns into a watermelon and oh yeah, a girl’s face literally falls off and reveals…hell??? beneath the skin. It is a genuine sensory overload of unfathomable proportions that couldn’t be more perfectly designed for a midnight matinee, crowds howling and cheering with every scene.

It is also a deeply misunderstood and even more deeply discounted movie—thanks to its singular aesthetic, it is inevitably seen as little more than wacky and crazy instead of wacky, crazy, and a deeply affecting lament for the post-war generation forever trapped in the scars of their parents—and frustratingly treated like a one-off gimmick instead of a piece of the puzzle that is one of Japan’s greatest and most important directors.1

So yes, the movie House is a lot of things. Too many to even count, in fact.

It’s also, vitally, not just a movie.

—

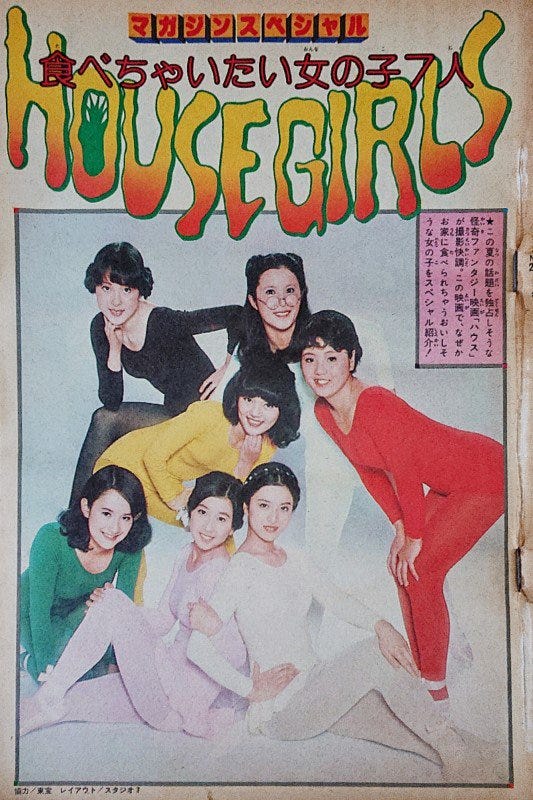

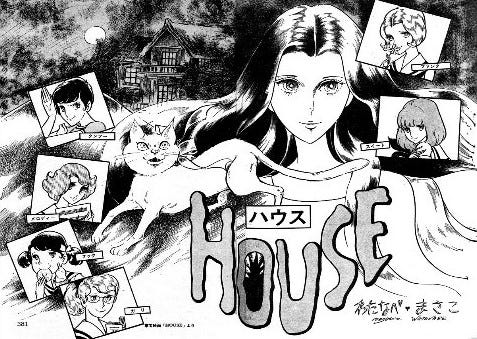

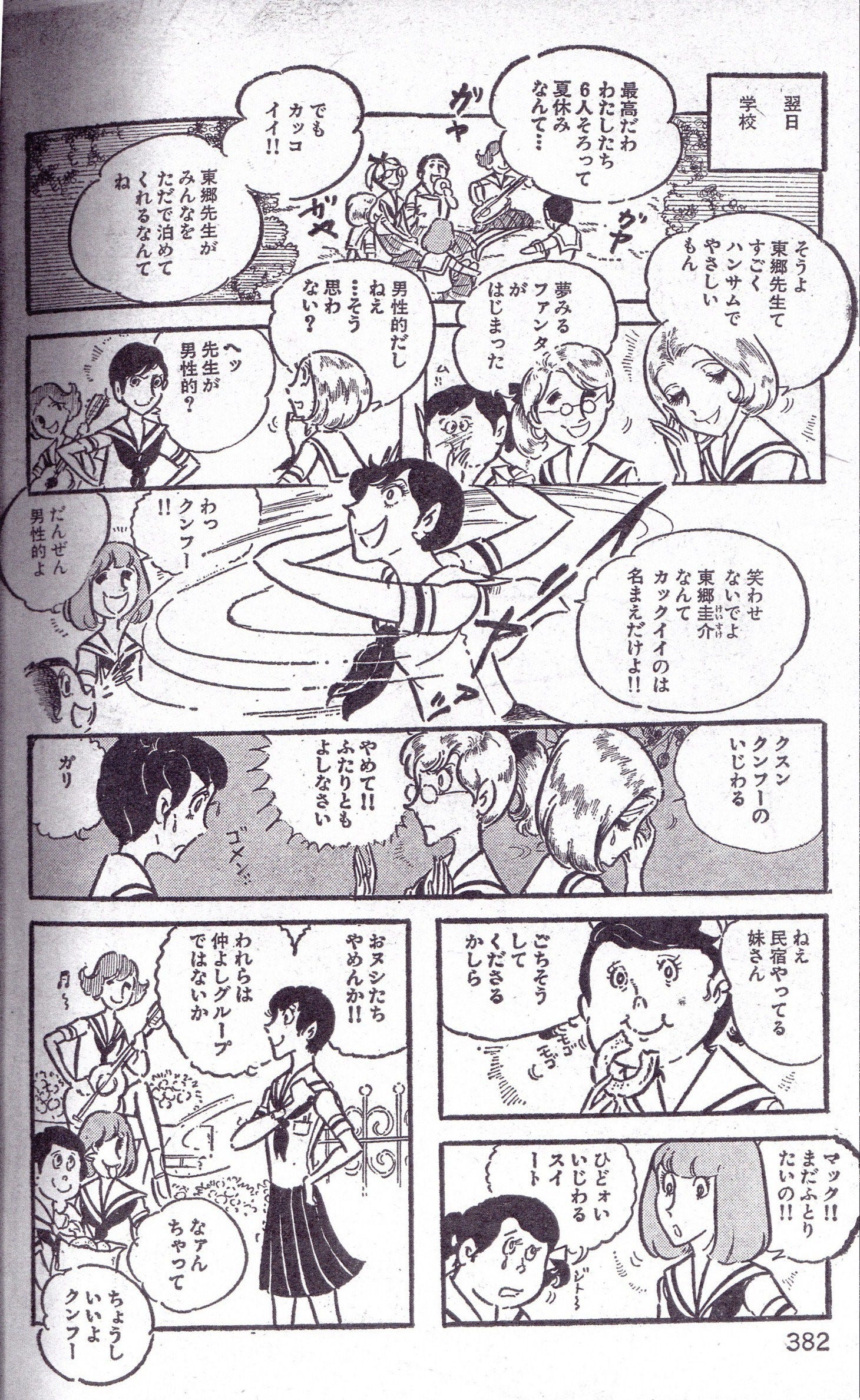

Published in June of 1977, a few months before the movie’s release, in Monthly Shounen Magazine under the periodic “Magazine Roadshow” feature that focused on comic adaptations of upcoming films, Miura's manga serves as a fascinating companion piece to the movie. Stripped of all but its most essential parts with only a tight twenty pages to work with, the manga rips through the story with the energy of a clip-show, deaths coming fast in a rapid cavalcade of absurdity. At the same time, unlike the movie, which revels in buckets of blood and dismemberment and surreal mayhem, Miura’s soft, clean artwork makes for an adventure that is more immediately comprehensible, the classic House question asked earlier (What is even happening??) rendered unnecessary. As quick as they are, things make sense, they are easy to parse. It feels, in almost all ways, like what it was intended to be: a Cliff Notes advertisement; a simplified adaptation without the dense stylistic assault obscuring its base.

But make no mistake, the bones of House—the things that really matter—remain: largely excising the more direct WW2 connections, the manga retains Obayashi’s generational critique, exploring with impressive brevity the fear of growing old, the longing for the past, and the ways that our parents and grandparents contain us, imprisoning generations in a past they had nothing to do with. 2

Four years, Miura would finally break big with the hugely successful rom-com The Kabocha Wine, dream finally realized after a decade of tireless work.

And so the story ends, a hungry author leaving a small imprint in the history of a movie as he rose to become a legend.

Except Miura wasn't the only one dragged into the world of House. He wasn't even the first.

—

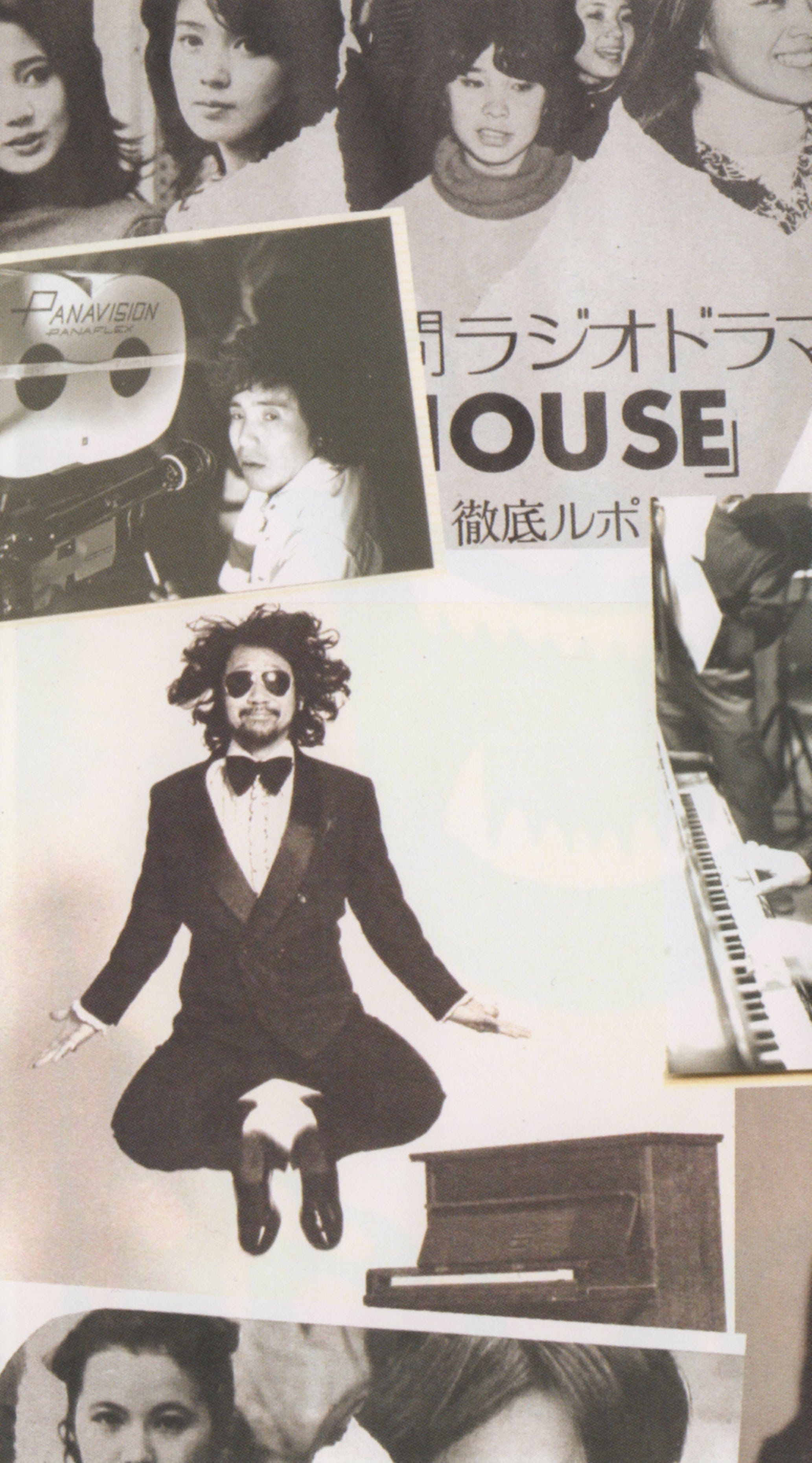

On November 27, 1976, nearly a full year before the movie's release, a radio drama aired on All-Night Nippon, a perpetual staple of late-night radio in Japan still on the air some forty years later. Done live and lasting a staggering four hours to take the record of the longest live radio drama ever produced in Japan to that point, the program featured not only its own narrative, but interviews and music and call-in segments for audience to share ghost stories. It was called House, and it was advertised during broadcast as having an upcoming film from Toho studios.

The radio drama portion of the broadcast both is and isn’t the House we know. Co-directed by Osamu Ueno and Nobuhiko Obayashi himself, and starring a miniature army of then popular idols, much of the experience is certainly familiar: the characters are still present, the house is still deadly, and the music, composed by Asei Kobayashi and performed by rock band Godiego, is largely what would end up in the movie itself. It even impressively captures Obayashi’s playful, free-wheeling psychedelic energy, characters introduced through their own sung theme songs and memories represented as the sounds of old-timey radio. Yes, it is House in audio form in so many ways except for one: the story is wrong.3

While the movie (spoilers) centers around the vengeful spirit of one of the character’s aunts, who died waiting for her fiancé to return from WWII, in the radio drama, the aunt is very much alive and there is no fiancé. Instead, her brother died in the war, and instead of inviting these girls to her home in a violent chase for youth, here she is fueled by revenge, determined to ruin the blood relatives of the seven men she believes are involved in her brother’s death.

The result is an almost immediately darker tone than the movie, a palpable sense of real danger lurking at every corner. This isn’t a story of longing and regret but one of hatred and desperation, where the living and corporeal are ready to create as many ghosts as they need. While Miura’s manga turns House into a cute play, and Obayashi’s film turns it into a fever dream, the radio drama takes House into its most traditionally horror form. With these tonal and narrative changes, it ends up playing like a pilot to the movie, a sort of test-run. Which is exactly what it is.

Though the broadcast was advertised as having a soon to be theatrical version from Toho, the truth is that when the radio drama aired, the movie hadn't even been approved yet. At the time, it was incredibly difficult for new directors to break into the industry if they weren’t already employed under a major production company, even for someone like Obayashi, who had spent over a decade revolutionizing independent cinema and television commercials. Even trying to was, to some eyes, a fool’s errand. But that wouldn’t stop Obayashi.

Like Babe Ruth pointing to the stands, he created the radio drama, aggressively marketed it and the idea of House, and called his shot: House would be a success and Toho wouldn’t be able to ignore him.

Obayashi went up to bat. He swung.

Homerun.

The radio drama was a hit. Perhaps even more than its commercial success, however, was the simple fact of Obayashi's unending enthusiasm and drive.

“We have so many directors right now,” Isao Matsuoka, then Toho’s planning manager who would ultimately greenlight the production of House, later said, “but they’re all just waiting there for luck to fall off the proverbial shelf right into their hands. But not Obayashi. He made his own shelf, stacked it with his own luck, and ate up its rewards. I couldn’t help but want to bet on that kind of energy.”

—

Shortly after the film's release, in September of 1977, yet another manga adaptation would be published, this time in Seventeen, a popular shoujo (a demographic aimed at adolescent girls) magazine and written by Masako Watanabe.

A giant of the medium and one of the most significant names in shoujo manga, Watanabe is as OG as they come, debuting back in 1952 (the same year as Astro Boy). Seventy years later and she's still going strong today, regularly publishing new titles at the age of 94. And while she is an author of considerable and varied talents, there is also no question that her real passion and mastery shines brightest in horror. One only has to look at one of her many masterpieces, Saint Rosalind, to see it: a riff on The Omen about a young girl who sees no issue with committing horrifying, gruesome murders, it is a delirious gothic melodrama heightened to its breaking point, petty arguments transformed into explosive pretexts for gaudy violence and evil.

She was, then, the perfect fit for House, which had become a hit mostly with a young female audience and which similarly existed in the world of hyper-melodrama.

Unfortunately, Watanabe's interpretation of House remains trapped in that old magazine issue it first appeared in, yet to be fully reprinted or digitized officially or otherwise.4 However, the few pictures there are online suggest a characteristically gorgeous interpretation that follows in the narrative footsteps of Miura's work while being completely her own: a romantic elegance hiding the sinister and evil just below its surface.

House is a lot. It is the work of four enormously talented creatives—Obayashi, Miura, Ueno, Watanabe—with four takes on the same material. It is a movie, and a radio drama, and two manga, but it’s also an entire history, a piece of art that has only grown and evolved and become more important with each passing year. House, in other words, is more than House.

It’s House.5

Music of the Week: Babi - Hana Furu Hi

Musician Babi, who spends most of her time composing for commercials, pulls out all the stops here for a slam dunk art-pop project that exists in the universe of the greats from the 80s and 90s; quirky and staccato and never standing still. But don’t think this isn’t uniquely her own. Putting her heavy composition skills to work, Hana Furu Hi is covered in intricate orchestration and surprising instruments. At points, entire tracks go by without hearing her voice at all, audience instead treated to something that sounds like nothing less than a toybox Debussy arabesque, hopping along dense and ornamental. One of my favorite releases of the year!

Book of the Week: Boogiepop and Others by Kouhei Kadono

The first volume in the expanse, long-running, and hugely influential light novel series serves as a perfect mission statement for what follows over more than 20 books: a moody, occult, horror action story with bizarre superpowers and characters named after bands ripped to shreds and reconstructed as a non-linear exploration of collective trauma and conservative societal pressures, everything you expect from its style of genre fiction deleted so that you can only sit in the ambiguity of the moments in-between. Just look at the first chapter, an incredible highlight, where the enigmatic Boogiepop periodically talks to a boy on a rooftop over the course of the entire story that is about to occur, anything resembling plot thrown out as unimportant asides. I am a freak for this series.

Movie of the Week: Bound for the Fields, the Mountains, and the Seacoast

Nobuhiko Obayashi’s career is bursting with all-timers. Even so, Bound for the Fields, the Mountains, and the Seacoast stands as one of his very greatest works—a stunning, haunting, emotionally and intellectually complex reckoning with the at-home horror of war, the specter of the bomb waiting patiently as it follows young children playing soldier and falling in love and desperately trying to escape the fate of the adults. It is perhaps his angriest movie, a cinematic scream so loud and so long that everything inside the body is expelled until there is nothing left but a hollow emptiness. It’s also beautiful and joyous and sad and every other emotion there is as it barrels towards one of my favorite endings in movie history.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here’s a huge interview with legendary animator Toshiyuki Inoue about The Boy and the Heron

I love House, it is a perfect masterpiece, but it probably isn’t even a top 10 Obayashi movie. ↩

You can read my translation of Miura’s House manga here! You can also find it on the Internet Archive ↩

The radio drama was uploaded to SoundCloud by Ai Matsubara, who played Prof in the film and Mac in the radio version! ↩

One of my life's missions is to get my hands on a copy and translate it. One day... ↩

Sources: