Talking movies | Urusei Yatsura 4: Lum the Forever

dissecting the ultimate anime girl

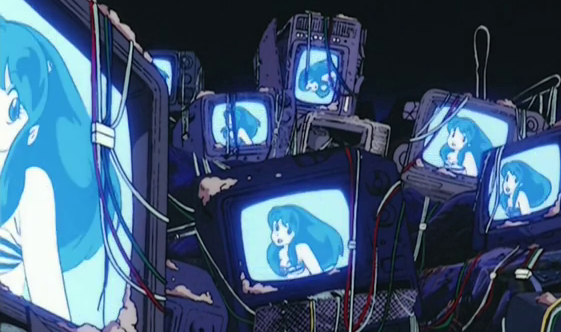

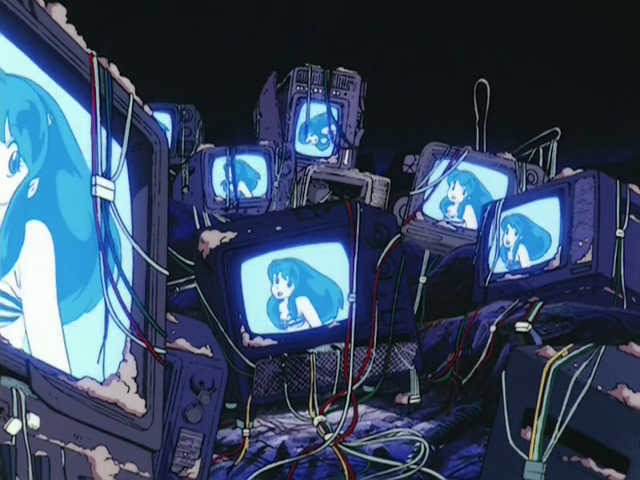

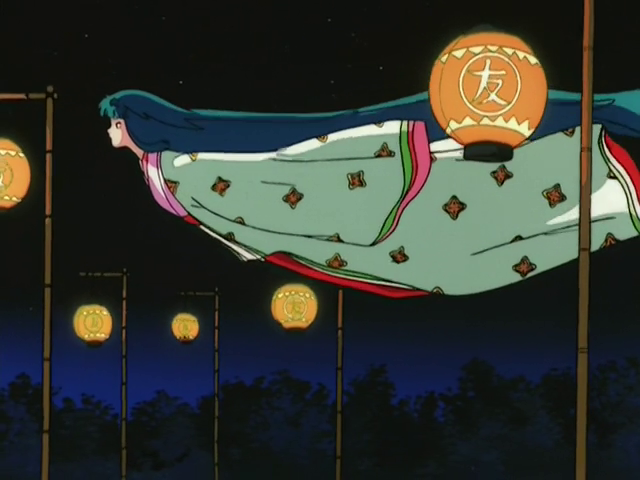

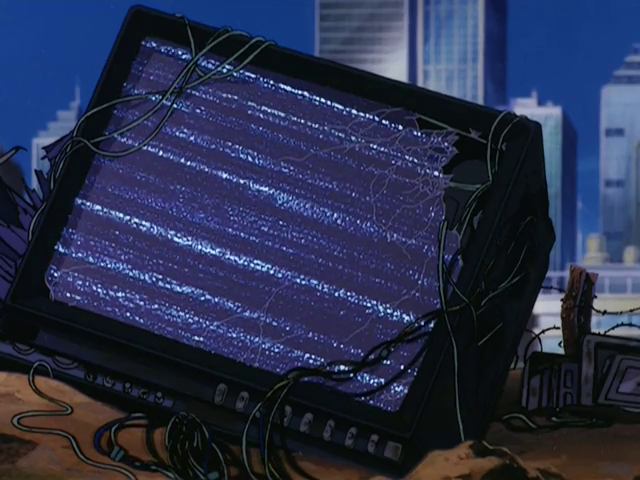

A mountain of TVs sit abandoned in a junkyard, CRTs on CRTs draped with stripped wire and cable like vines and veins. They rest surrounded by the rest that we've forgotten--the old bikes, the unwanted microwaves, our abandoned toys and broken chairs. But then it happens. Unplugged, all those TVs hiss to life in unison. In some sort of great, unknown unity, their screens fill with static that lights up the night more any moon or stars ever could, and then that snow slowly gives away to something more concrete. An image. A girl, beautiful, smiling, perfect and still. Her name is Lum and she's about to end the world. Maybe she already has.

What is Lum?

This is a question that has plagued comedy manga and anime Urusei Yatsura since its inception in 1978, bursting onto the scene like a rocket with its unendingly dense torrent of referential pop culture imagination. And sure, the answer seems easy enough—she’s a super cute alien oni gyaru with electric powers and a tiger-print bikini madly in love with serial womanizer Ataru (okay, typing that out I'm realizing how not easy it sounds lol)—but like, what is she?

Because if there's one thing she isn't, it's JUST a super cute alien oni gyaru with electric powers and a tiger-print bikini madly in love with serial womanizer Ataru. She's the first lady of anime, the original waifu (tasted a little vomit writing that, but it’s true), a paradigm in hot cartoons, an idol, a sex symbol cosplayed more than near anyone else who helped usher in that entire mode of fan expression in Japan. Lum is as iconic as they come and, in many ways, represents the beginnings of the modern otaku—the nerd—as we know now it, a character that’s gained her own gravity and altered the very fiction she exists in, escaping out into our world as a major representation of her entire medium.

So again. What is she really?

The movie Urusei Yatsura 4: Lum the Forever, directed by Kazuo Yamazaki, is an attempt to answer that impossible question. It’s an attempt to figure out what Lum, this girl turned icon so much bigger than any fiction could ever hope to contain, is. And it might just have succeeded.

By the time our movie begins, the characters themselves are already deep in the throes of making their own. It's a messy low-budget flick they’re producing, a crazed mishmash of slasher, zombie, and folk horror all rolled into a surreal comedic ball, not unlike the genre blender series they themselves exist in. And in their movie, much like ours, there is Lum, precious reels of film not used for plot or action but to capture the beautiful center and lifeblood of the series as she walks to school or plays with birds.

And then they cut down a tree. Older than old and bigger than big, the ancient, slowly dying symbol of their town, Tomobiki, is killed for their film in order to make way for Lum. She’s the new symbol of this town after all, the new reality. What use is this object holding memories of a past too old for them to remember themselves?

From here until the end of the film, dream and fiction and memory increasingly begin to blur. The essence of the tree tries to absorb Lum, who loses her powers and, in effect, the town falls out of their eternal love with her. Nightmares crystalize like ice next to alternative possibilities of what could have been and what currently is as earth and soil shift to create a new set of memories of its inhabitants. The story becomes rewritten, as if Lum truly was never part of it.

It’s a lot, I know, but for as meta and contemplative as this all sounds for what’s supposed to be an outrageous comedy series, it doesn’t come out of nowhere—Lum the Forever is very much a piece of the Urusei Yatsura films that came before, its three predecessor’s all increasingly obsessed with ideas of memory and reality, change and stasis, time and fiction. While the second, Beautiful Dreamer, is the most famous (representing the beginning of director Mamoru Oshii going full, unapologetically auteur), the third, Remember My Love, which was Kazuo Yamazaki's first film work, mines remarkably similar narrative concepts. That movie similarly focuses Lum vanishing from the town and with her, the zaniness of the series. Without her, the magic fades, reality starts to seep in, and eventually, time begins to move. The weekly structure breaks. The comfort of repetition is killed.

Lum the Forever essentially acts as a follow-up to this idea, side character Shinobu commenting early on about how calm the movie has been up until that point, how natural, how un-Urusei Yatsura it all is. And once Lum does vanish, everyone becomes violently desperate (literally) for the return of the status quo, the town starting a war with itself in the vague hope that through destruction, their memories of the past will actualize and return life to the comforting structure it once held like it always does. They all hunger for the known; they need the circle of time. They need Lum.

Urusei Yatsura, like most episodic stories, represents the ultimate dream of escapism: a chance to imagine an interesting, exciting life with interesting, exciting people and interesting, exciting things happening every single day without the awful promise of time cutting it all to nothing. Every week, things reset (very explicitly early on where chapters had a tendency to end with either the world ending or the protagonist Ataru almost definitely biting the bullet) and every week a new adventure takes place. And while the manga does employ author Rumiko Takahashi's supernatural talents at slow, subtle character development, it still exists in this odd stasis. Why shouldn't it? Who wouldn't want that? How wonderful would it be to not age, to be with the people who matter most to you, to exist perpetually in the romance of a still blossoming love? We might not be able to have that in real life, but we can have in the form a chapter and an episode week after week.

In that sense, Lum might be the ultimate representation of the eternity of the series. It’s been nearly fifty years, and Lum hasn’t aged a day. Quite the opposite—she’s gotten younger, design updated and voice altered in subtle little tweaks to keep her modern and young all over again even on the conceptual level while simultaneously remaining as you’ve always known her. She has begun to abstract in the same way other icons have—think Doraemon or Mickey Mouse— transcending into something more, into a commodity and idea. Watch her sell shoes and shirts, watch her emerge from a million gacha machines in a million new forms, watch her exist divorced from context once attached. Lum will never change now, not really. She can’t. She’s simply not allowed.

There’s this thing you hear sometimes, both by artist and by fans, that certain characters or stories don’t belong to the author anymore. Star Wars isn’t owned by Lucas or Disney but by all of us; Touhou isn’t ZUN’s child but everyone’s. You can occasionally see some try to push this idea into more political territory as a way to reconcile and shed artists who have betrayed trust and goodness in some way. Harry Potter was actually written by Hatsune Miku, who would never be a violently transphobic monster. She coincidentally also created Minecraft instead of…well, another violently transphobic monster. And while I might be deeply unconvinced of those attempts (pretend all you want, Miku isn’t the one getting your money or silent acceptance) the point is, all of this art has escaped their origins on some level, broader culture doing what it can to mutate them into its own desired image, to change the reality of the fiction.

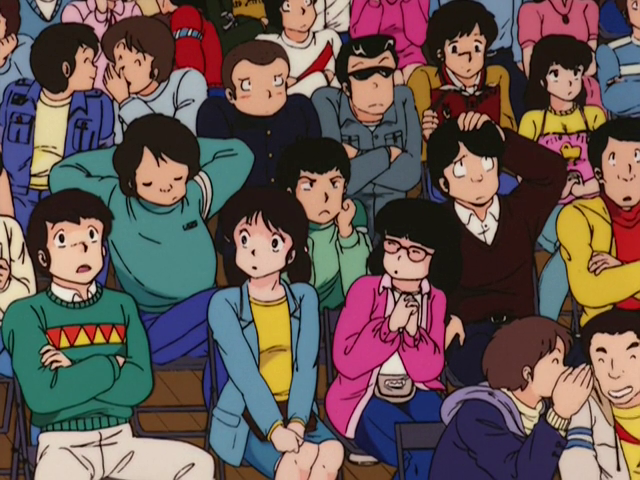

In a scene of a town hall meeting in Lum the Forever, the camera hangs on a shot featuring three characters in particular. Two of them are Godai and Kyoko, protagonists of the concurrent Rumiko Takahashi series, Maison Ikkoku. The other is Takahashi herself. It’s a cute reference, but it also suggests this reality of her work. She’s just part of the crowd now, one of many, enveloped in the idea of Urusei Yatsura like everyone else.

But at the same time, what makes Lum so unknowable, so difficult to nail down, is that she doesn’t belong to you. She doesn’t belong to her fan club or to Mendou or Shinobu or Sakura or Cherry or Ataru, as much as you and they might wish otherwise. She isn’t your wife nor is she your reason for living. She can’t be; she mustn’t be. She isn’t real, just a part of a story made up for fancy and fun, written by Takahashi and directed by Yamazaki and voiced by Fumi Hirano and drawn dozens of assistants and animators and based on the real-life model Agnes Lum—real people, really alive, existing here and now (and then and there) to create the figure we call Lum.

She is born from a collective, and then given to an even bigger collective. She is imagined, actualized, turned into memory by readers and viewers, and then imagined all over again. The cosplay, the songs, the advertisements, the dreams. People, knowingly or not, unite under her—we wage a war for this anime girl just as much as the characters do. She exists as a contradictory superimposition of fiction within itself and reality. She belongs to everyone and no one. She’s different for us all, unique to each and yet the same to all, a personal figure living deep in the collective consciousness.

As the movie ends, a junkyard TV cuts to black. It’s never been plugged into anything, after all. The camera drifts down into the earth and the credits roll. People’s names, real people, buried in rock and dirt, the soil from which cathode rays grow. The spirit of the tree speaks out. “The upper world belongs to all of you.”

What is Lum? You already know the answer. You always have.

She’s just a character. Nothing more, nothing less.

She’s forever.

Music of the Week | Fani mani by KOM_I & Foodman

KOM_I, the original frontman for mainstream but still weird and cool project, Wednesday Campanella, returns to us like a light shone down from god in the form of an EP collab with footwork legend, Foodman and the results are about as awesome as you’d expect. Taking heavy influence from her time outside of Japan (mainly India), Fani mani chops and twists simple phrases and traditional instruments into increasingly hypnotic electronic rhythms. It’s only fifteen minutes, but it’s fifteen minutes of gold, a release that’s dangerous to listen to in public because you will unconsciously start moving your entire body to the trance.

Book of the Week | Schoolgirl by Osamu Dazai

Dazai is now most remembered for his final novel, No Longer Human, but he was a man who racked up a list of multiple masterpieces in his tragically short time on earth. Take Schoolgirl, the novella that catapulted him to the top of the literary world. Written from the perspective of a young girl, it is an absolute masterclass in first person narration, gorgeously exploring the frank, messy, uncomfortable, beautiful, and always contradictory reality of all those thoughts all of us have. Reading every single paragraph here feels like being seen for the very first time in both ways you wish others would and in ways you pray they never do. Flat out, unquestionably perfect.

Movie of the Week | Talking Head (dir. Mamoru Oshii 1992)

If you regularly read and like the kind of things I talk about and you haven’t seen Talking Head, go do it NOW. A profoundly Tsundoku Diving type of movie, this strange narrative as essay about an anime director stepping in to complete a cursed production is basically two hours of philosophizing about the medium, the ways the physical tools used to make art impart meaning, the lies of fiction and how everything in our lives is ultimately just stories…you see what I’m saying? Like if every post on this site was crunched together into a single, beautifully artificial post-modern slasher. One of those movies that feels like an expose on my own brain.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh and I scanned a bunch of beautiful Unlimited Saga art by Tomomi Kobayashi here