Talking movies | WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3

The forgotten sequel and the death of memory

When the monster in WXIII: Patlabor the Movie 3 screams, it screams like a human. In sharp contrast to its massive size and horrible segmented body filled with teeth and edges, and the way it swallows people up and leaves nothing behind but blood and destruction and loss, a shrill wail comes out of it like the crying of a child. It’s a sad sound, a pathetic sound. It's a sound that echoes everywhere throughout the movie.

Released in 2001, WXIII is a black sheep in a family full of black sheep. Created as a multi-media franchise in the ‘80s by powerhouse collective Headgear, Patlabor has always been a remarkably malleable series: Set in a near distant future where giant robots are used for labor and construction (and are appropriately named Labors) and centering on a ragtag, underfunded police division that handle Labor related crimes, the franchise freely shifts from bureaucratic satire, to cold-war thriller, from horror, to action, relaxed pastoral drama, and slapstick comedy as easily as one changes clothes in the morning. It’s been an OVA (direct-to-video anime) a TV anime, a manga, a live-action series, and a series of novels. But it’s most known for its movies. The first two, both masterpiece filmic essays disguised as political thrillers—these dense ruminations on post-war Tokyo filtered through icy conspiracy and bursts of sci-fi mecha action from the legendary creative combo of director Mamoru Oshii and writer Kazunori Ito—are now towering classics, canon entries in the filmography of one of anime’s most important directors. In the face of that, it’s maybe inevitable that the world didn’t accept the third movie quite as readily.

After all, this is a movie that shuns the main cast of the series to the shadows much in the same way it moves away from the original creative team, shifting focus to two detectives—brand new characters with no previous connection to the rest of the series—as they are drawn into a slow-burn kaiju (giant monster) noir. It’s a movie that for most of its run shows very little interest in the Labor robots that made the series so iconic or the political concerns bubbling underneath the entire franchise; a movie where for long stretches you could be convinced that it isn’t just unrelated to Patlabor, but that it isn’t even sci-fi at all.

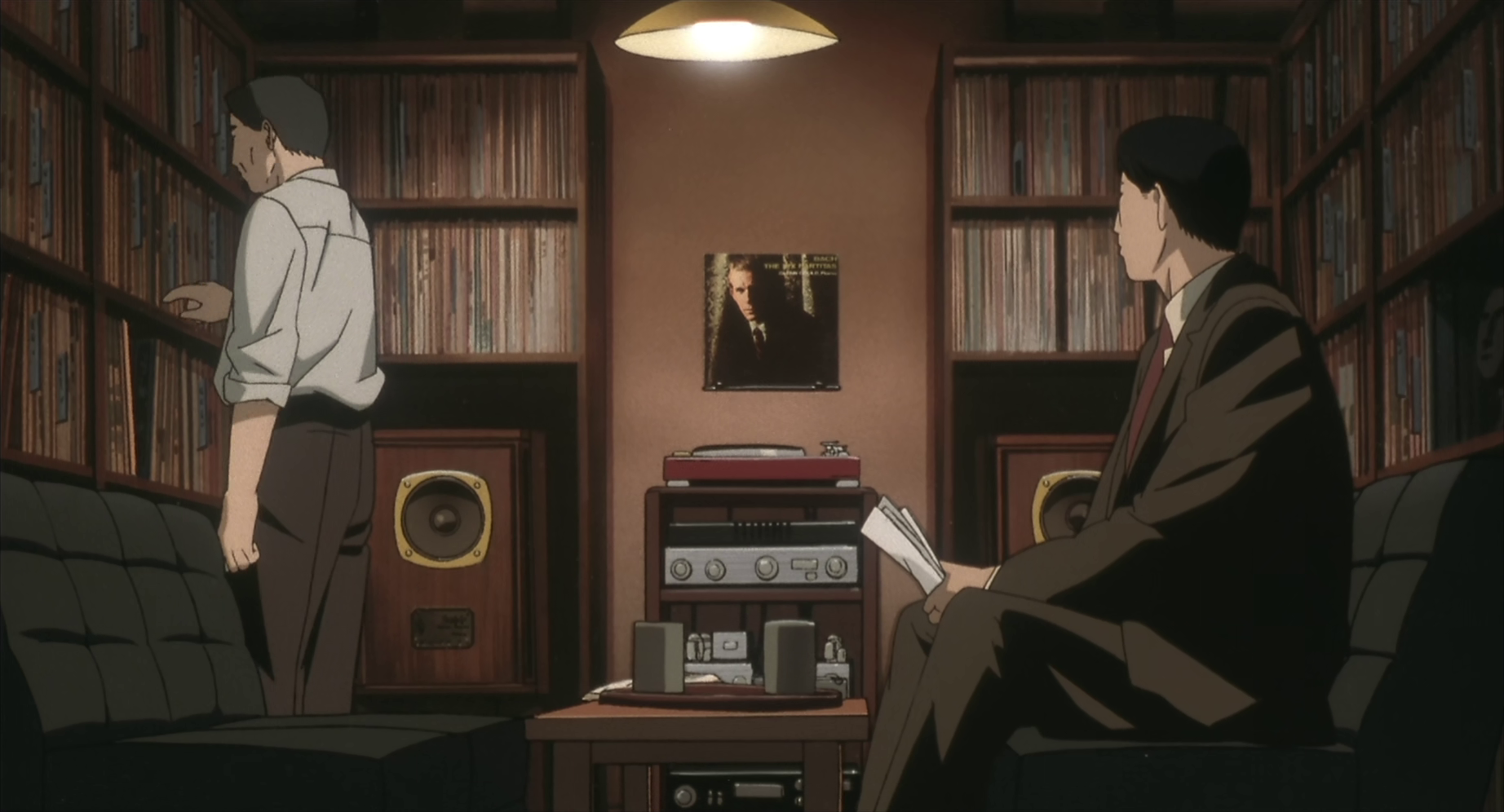

Those detectives, Kusumi and Hata are the first to hear the monster’s cry. They fight for their life and leave it screaming with a chopped off finger in a strangely muted action scene, pomp and bravado and thrills rendered through methodical silence. Later, Kusumi returns to his apartment and listens to some records. Family abandoned in the face of an obsession with work, his apartment is small, simple, run-down, and filled from head to toe in vinyl records. There are so many that you can’t even see the walls anymore. It’s just about the only thing he has left anymore.

Hata, for his part, fresh-faced, full of hope, and finally off cigarettes, picks up a woman with car trouble at the beginning of the movie. He doesn’t know a thing about her except that she’s beautiful and kind and holds a depth inside her she doesn’t let others see. She accidentally leaves her lighter in his car. Maybe it’s thanks to that, but he can’t get her out of his head.

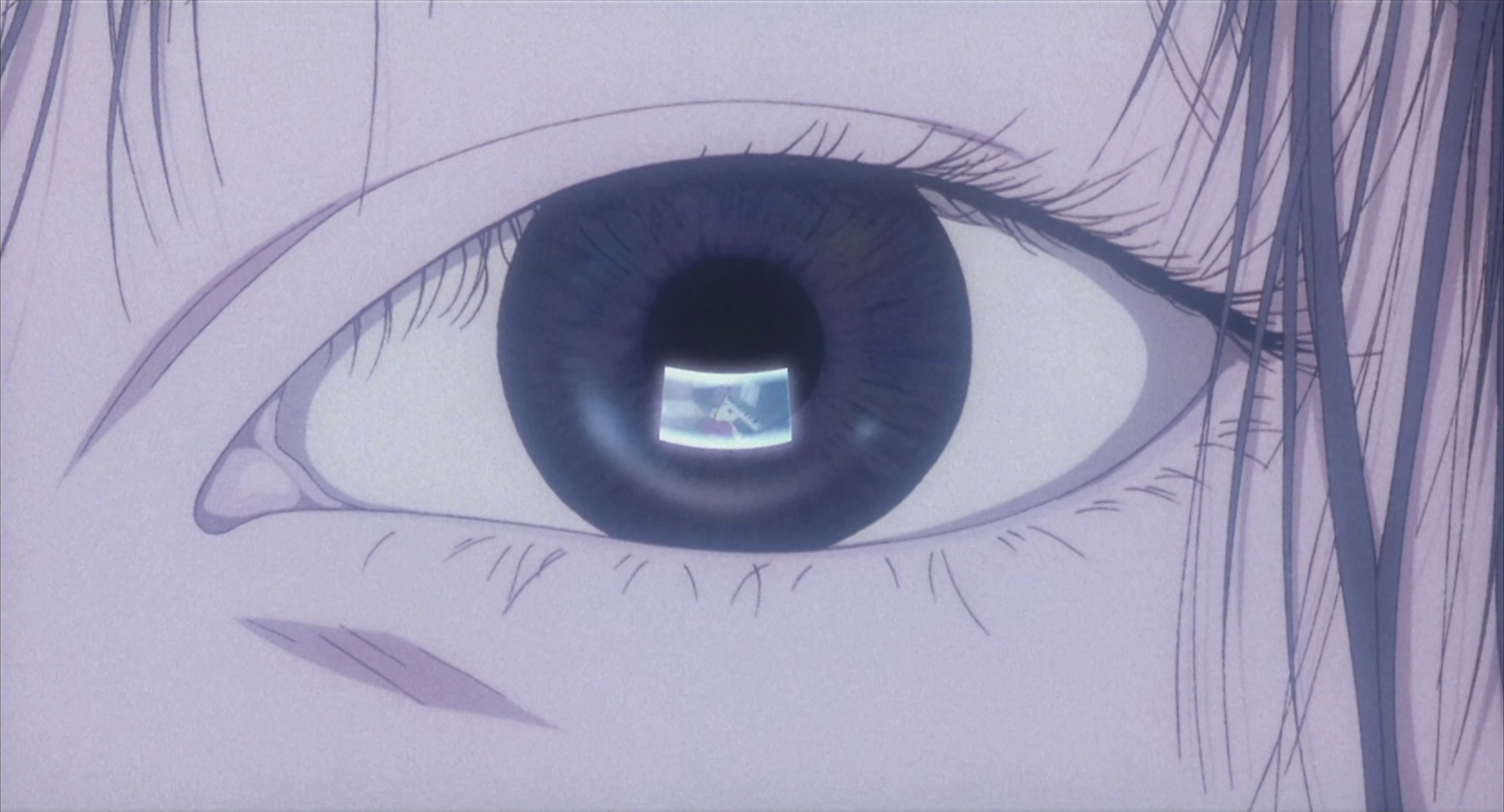

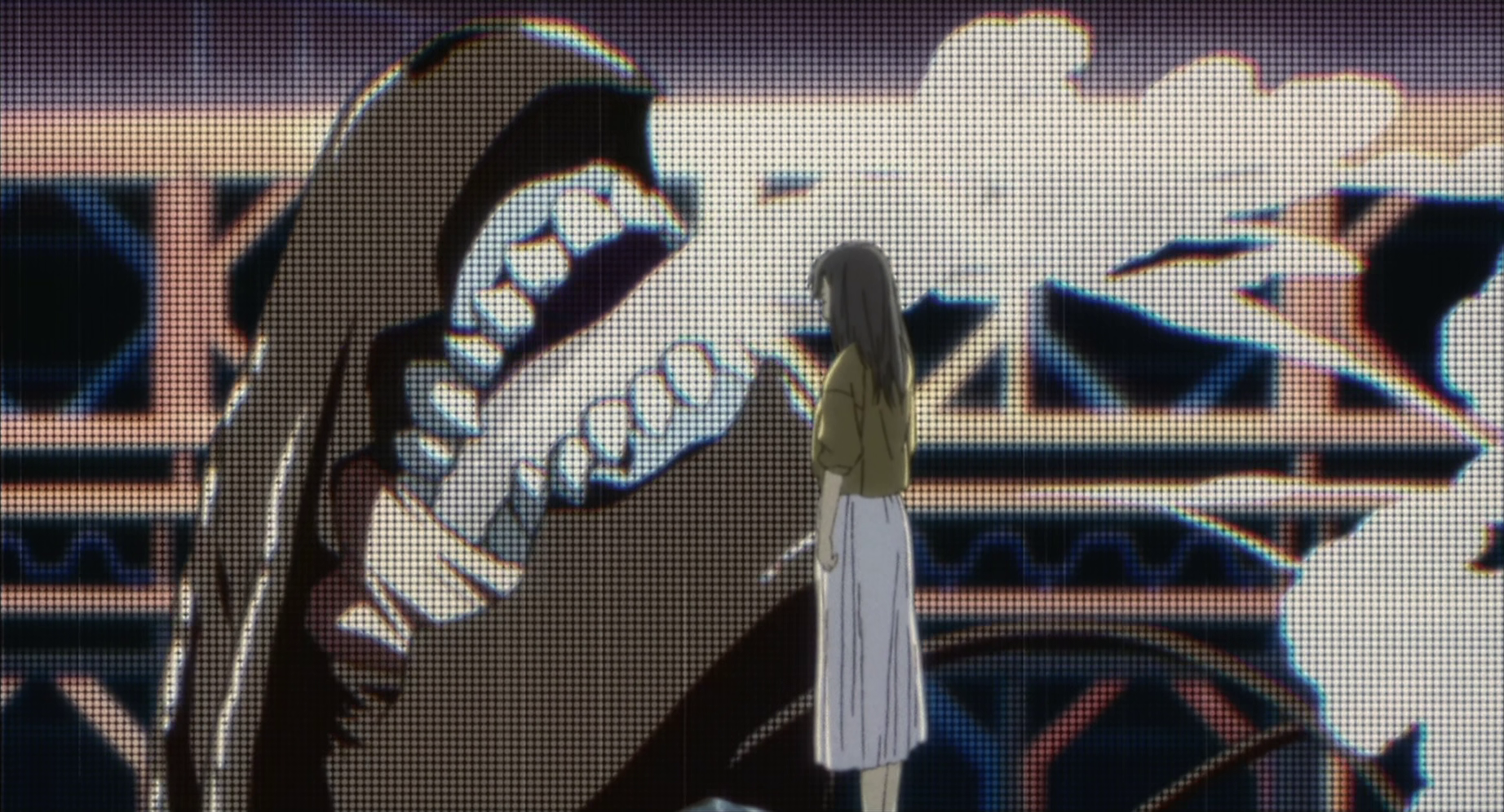

Her name is Misaki, and like Kusumi, she spends her time at home alone with media. Only in her case it’s the TV. Lights off, cathode rays searing, she plays old VHS tapes of a family and a daughter no longer with her over and over on repeat. The image reflects large in her eye. It’s starting to give way to static. She’s starting to forget.

Written by Miki Tori, WXIII is a movie that cries like the monster. It’s a dense, muted exploration of memory and media, of the objects we surround ourselves with and the cities we live in filtered through franchise filmmaking and horrible creatures. Everywhere you look in this film, the seemingly clear distinction between media and geography is collapsing. Almost everybody here seems to very literally live inside media formats, replacing their homes with different ways to remember. But media dies. We know that’s the case with film and VHS—it’s easy enough to see there, repeating viewing creating scratches and hazes and makes colors bleed until a strip snaps or it all becomes complete visual noise—but it happens with everything. Books age, paper becoming brittle; JPEGs blur pixels in a constant progression of compression; discs rot in ways you don’t notice until its too late or scratch off vital information; vinyl warps; paint chips; pictures fade. It’s all so ephemeral, as much as we desperately try otherwise.

They die like our memories die, slow and shifting.

They die like us.

Tori is a deeply inspired choice of writer for the film. A gag manga artist without a single other screenwriting credit to his name, he’s an absolutely perfect fit for Patlabor’s malleable blend of slapstick, heady sci-fi, near academic intellectualism, and satire. I’ve written previously about his masterpiece Dai-Honya (it was one of my first posts and probably isn’t very good lmao), which manages a very similar balancing act, but here Tori completely excises his comedy roots for something deadly serious and endlessly contemplative (it’s the least “fun” of the three films, which is saying a lot), fully wallowing in the complex concerns with our relationship to art and object that defines much of his work.

At one point Kusumi and Hata, suspecting Misaki is involved with the monster in some way, investigate her apartment. In it, they find a photo of her deceased daughter. She’s smiling, she’s happy. She’s been printed out and blown up to the size of a wall, completely consuming Misaki’s room until there is nothing left there but her.

The monster that cries like a child isn’t one. A human that is, not really. It’s a fish, genetically mutated, created from a compound made using cancer cells to imitate their rapid parasitic spread. It’s created from one of the most awful and terrifying things about our bodies that despite everything we’ve done we are so frequently still powerless to stop. It’s created from what killed her daughter. It’s created from the cells of her.

In that way, the monster at the center of WXIII is no different than the picture in Misaki’s room. It’s no different than a bunch of records, or a lighter, or a faded VHS. It’s just another vehicle for memory, a violent tool for remembering. We invent and create and birth and multiply all to protect our past, to let it continue into the present, to allow it to live forever even though forever is impossible. But video or audio or picture or the images that play in our head are never the truth. As time passes we start to forget, replace bit of what we remember with invented details and fantasy; as media ages pixels are blurred and frequencies are lost until it’s something entirely new. The monster is alive. It’s spreading, it’s distorting. It’s dying.

The climax of WXIII takes place in an arena retrofitted for the filming of a music video by an American band. In the climax, the monster is wearing labor armor. It crawled inside a robot and got stuck. As they fight and kill the monster that both is and isn’t Misaki’s daughter, they play a recording of a piano recital she had before she died. The monster is filmed and projected even larger than it already is onto the arena’s jumbotron, Misaki standing there watching and hearing what she always wanted—for the past to return and live again—as this awful fiction of her daughter is murdered, image blown up behind her and consuming her entire world.

I don’t think I need to tell you that there isn’t really a happy ending here. The story is a zero-sum game: there can be only losers on any side. Yes, they kill the monster, but what does that mean? Does it even mean anything? Misaki kills herself. Kusumi has a moment of silence. Hata starts smoking again. Life returns to the way it was before. Tokyo continues to move. It continues to spread, filling with new memories and destroying others as it grows. Is it any different than the monster? Is it any different from a hazy VHS?

Is anything?

Music of the Week | Strikes Back by Electric Glass Balloon

At times you could believe it’s a classic ‘80s jangle pop, at others part of the new wave of space rock, and at others still some weird lost slab of baroque psych pop; Electric Glass Balloon fill their early indie vibe with all sorts of sounds—strings, horns, electronics, backing vocals and choirs—to back a band so full of energy they feel on the verge of collapse with every chord. The dissonance between careful construction and haphazard rocking is an absolute delight, only doubled by their ambition and willingness to turn what should be short twee excursions into these massive six-minute journeys.

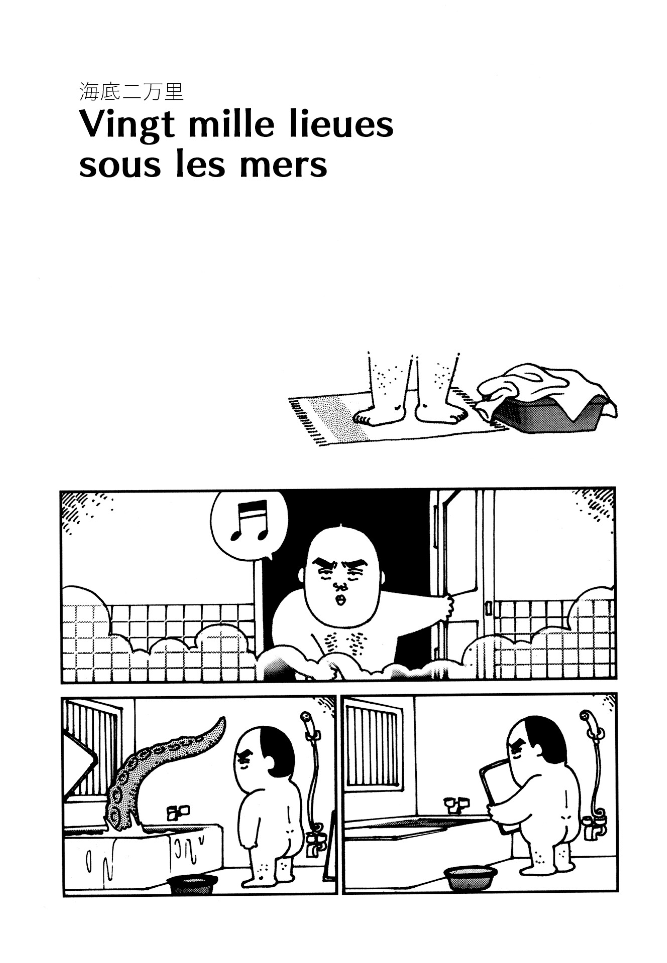

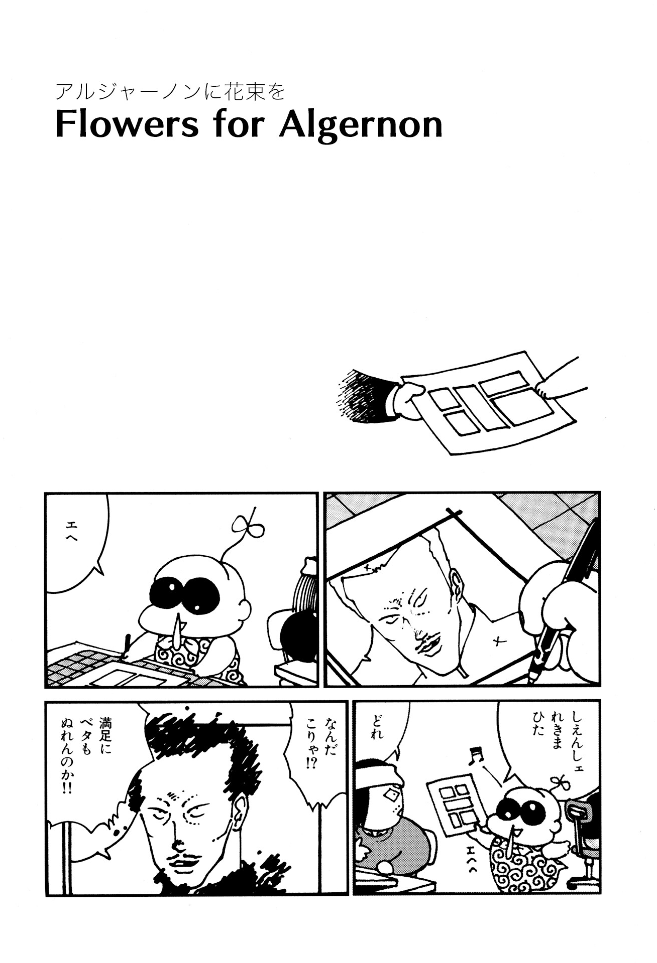

Book of the Week | SF Taisho by Miki Tori

One of the best examples of Miki Tori’s talents, here’s a strange little collection reinterpreting classic sci-fi stories into surreal comedic vignettes. Hyper emphasis on the reinterpreting part, as you’d probably struggle half the time to get the connection without the titles. Absurdist, weird, hilarious, and deeply clever, this book shows an artist with an understanding and appreciation for genre far beyond the surface level—something to love on its own but which also deepens your love of the source material.

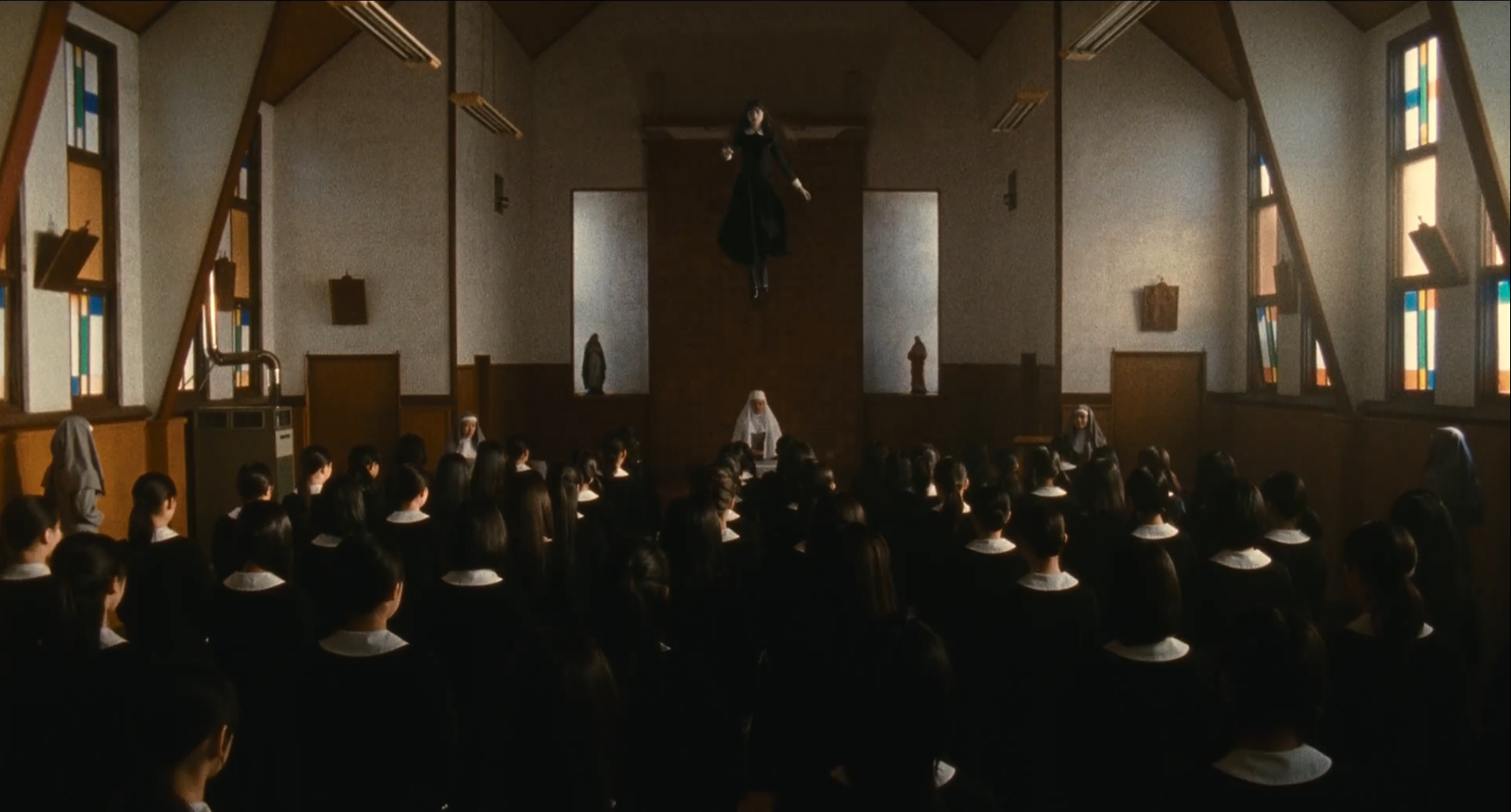

Movie of the Week | Fatal Frame (dir. Mari Asato, 2014)

A loose take on the video game series (which I’ve written about!) directed by one of contemporary Japan’s best horror filmmakers, Fatal Frame has slowly seen its reputation grow after an initial “video game movies are default bad” dismissal. And boy does it deserve it! Drenched in both gothic and classic shoujo horror tones, this is an elegant, beautiful, and Definitely Not Gay ghost story set in an all-girls school. Busting with spirits as objects of melancholy and longing, and almost unspeakably gorgeous to look at, it just might be one of the best ghost films of the 2010s.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here's a great post about Linda Cube (it's Italian but you can translate it)