Talking theater | Evangelion Beyond

What exactly is Evangelion in 2023?

It starts with the news. A mushroom cloud, a crater, writhing bodies and a town lost; a meteor has crashed to Earth, the unavoidable, natural world erasing tens of thousands in the blink of an eye. All anyone can do is watch. All anyone can do is sit as names and numbers fill the screen, an already incomprehensible tragedy abstracted to letters and data in a futile effort to understand, to make it all bearable. There’s talk of alien titans emerging from the meteor called Angels, and there’s talk of a plan to stop them called The Evangelion Project. None of it makes any sense—how could it? How could anything make sense in the wake of something like that?

A reporter, just another among a faceless, anonymous crowd, asks the only question anyone really can.

“What is Evangelion?”

The screen goes dark.

What is Evangelion?

It is a question that has plagued the franchise since its inception, when the anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion, created by Hideaki Anno, first hit TV and permanently and irrevocably altered the Japanese media landscape. Its influence is towering and monstrous, the series’ bizarre blend of otaku worship mecha action and intensely interior psycho-drama opening the flood gates for an entire generation of manga and anime and games and movies to draw inspiration from both thematically, narratively, and visually. Evangelion is essential, required viewing for understanding contemporary Japanese fiction. Evangelion is vital, its shadow looming large even now, nearly thirty years later.1

Evangelion is dead.

To me, it died two years ago in 2021 with the release of the final film in its remake/thematic sequel series Rebuild of Evangelion, Anno finally closing the book on his story and his characters, but some will tell you it died long before that. It died with the aptly named End of Evangelion, or with the conclusion of the manga series, or with the controversial finale to the anime. It died when its characters became fashion models for advertisements, when its iconic imagery became a tool for hocking food and insurance and phone apps, when the series became a repository for fan-service heavy spin-offs—here it is a high-school romance, now a rhythm game, now strip mahjong—thematic and narrative depth stripped and agency violently removed from the cast to turn them into marketing symbols. It's been dead since the start, a series built on an endless cavalcade of references and allusions to other works patchworked together, a Frankenstein monster of media that birthed a dangerously rabid fanbase. Evangelion is dead.

So then what is this?

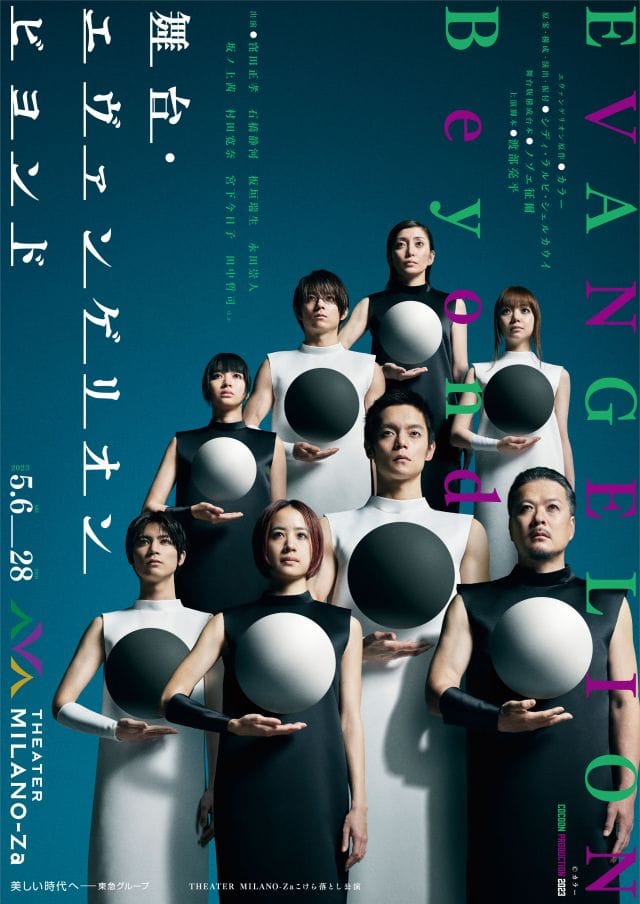

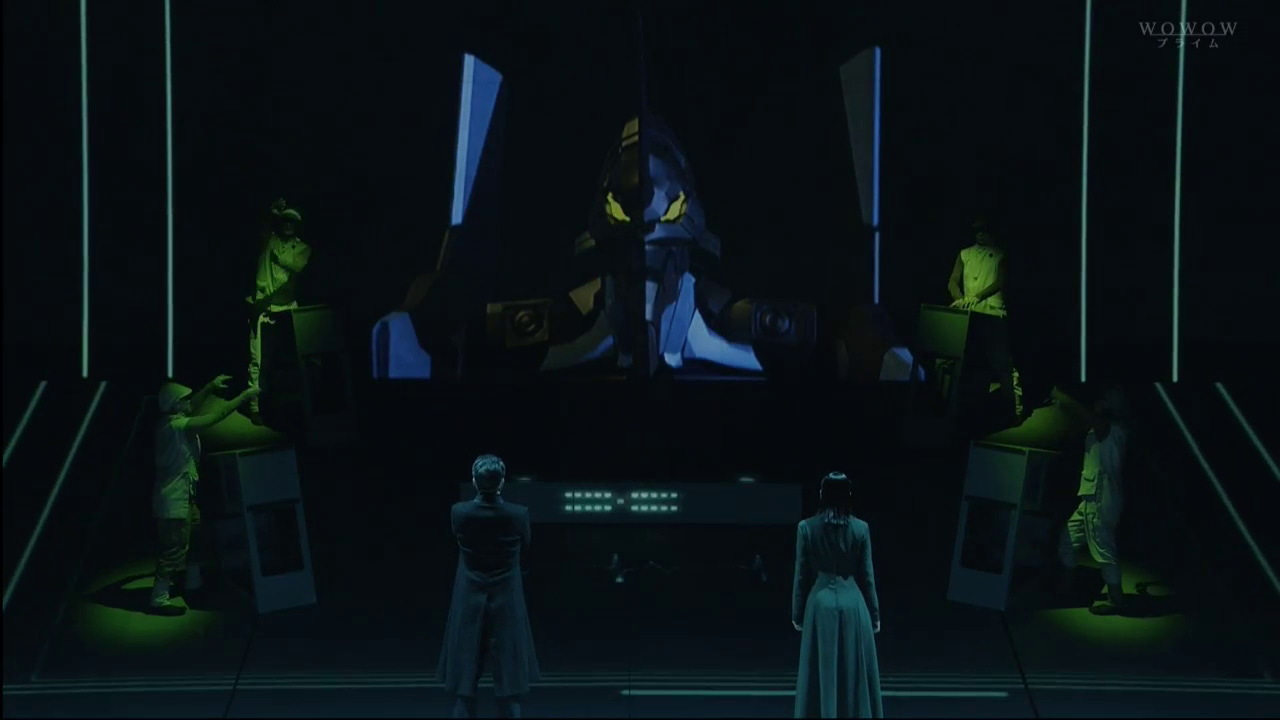

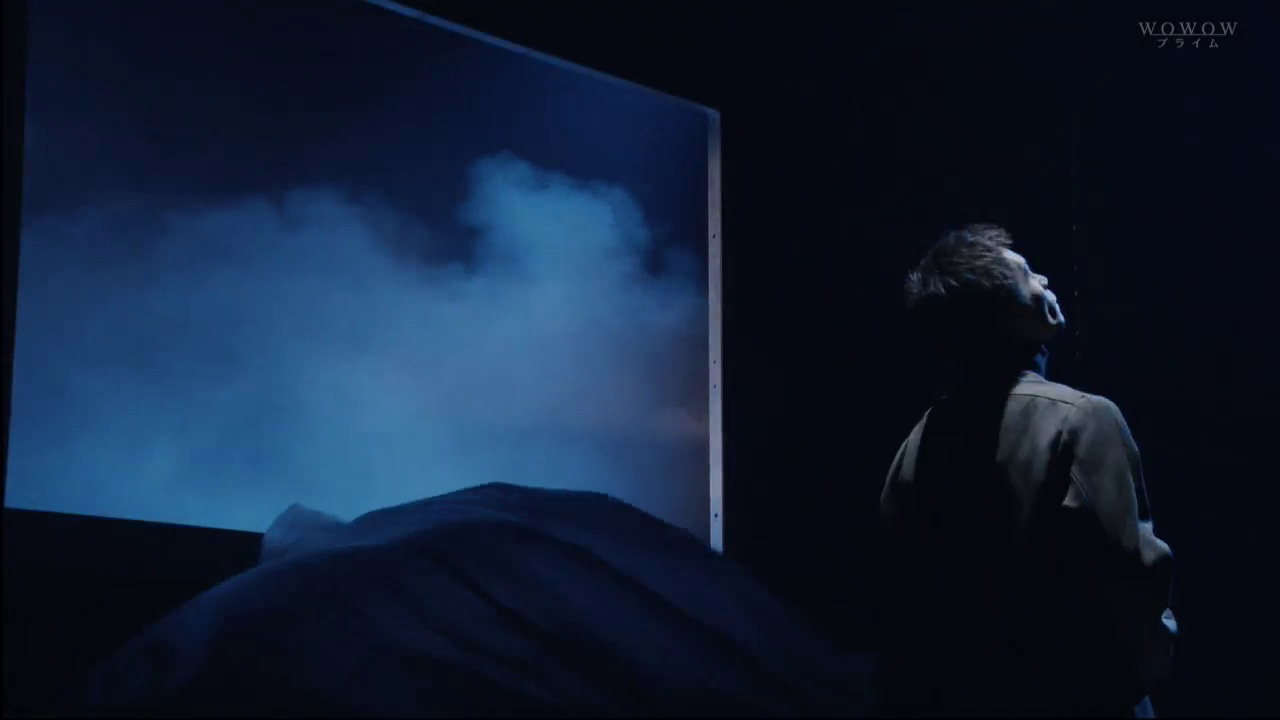

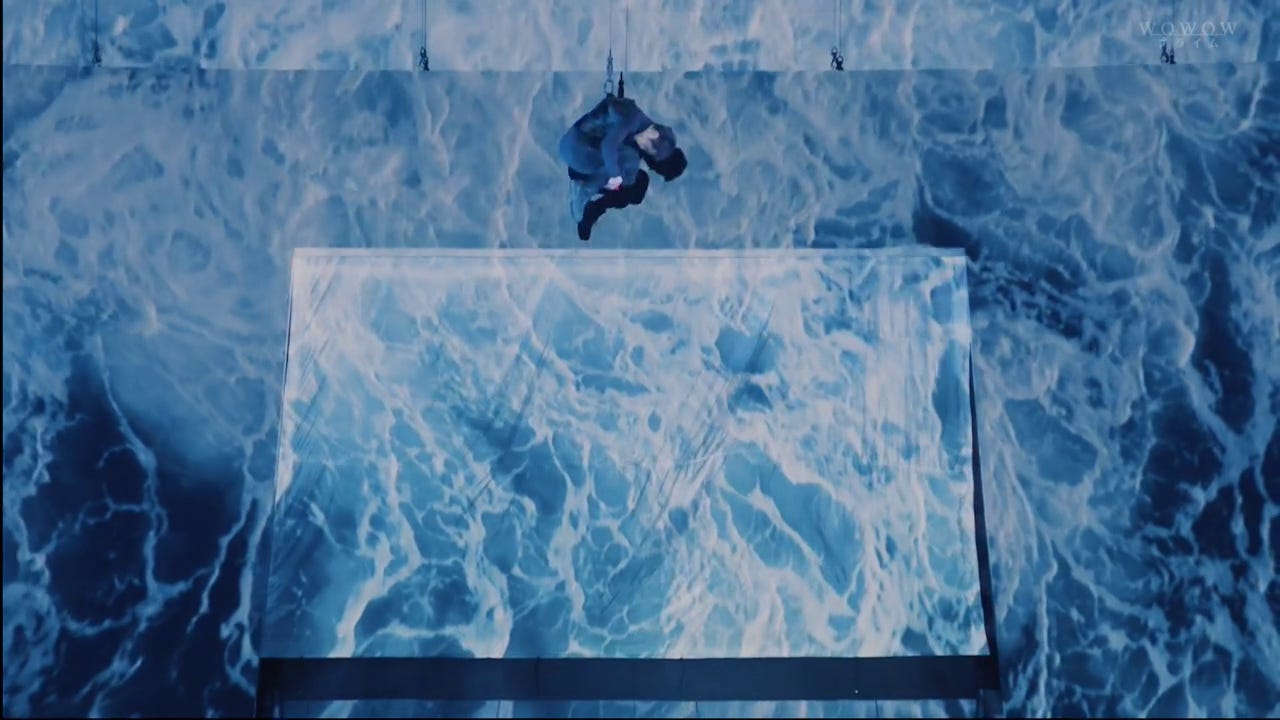

None of the characters the world knows from the series exist in Evangelion Beyond, the 2023 stage play developed by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui for the recently opened Theater MILANO-Za that rests high up in a building overlooking Shinjuku. Near all the details and plot beats and ideas that have become so associated with the franchise, so deeply ingrained in our understanding of Evangelion, are either missing or twisted into unknown new shapes. The number of pilots and angels is wrong too, the iconic designs have been altered, the giant Eva serve an entirely new purpose. Even more egregious are the names: it’s not Shinji, Asuka, Rei, but Touma and Hinata and Eri. It all feels so alien and strange. You look and for a moment wonder: is this really Evangelion?

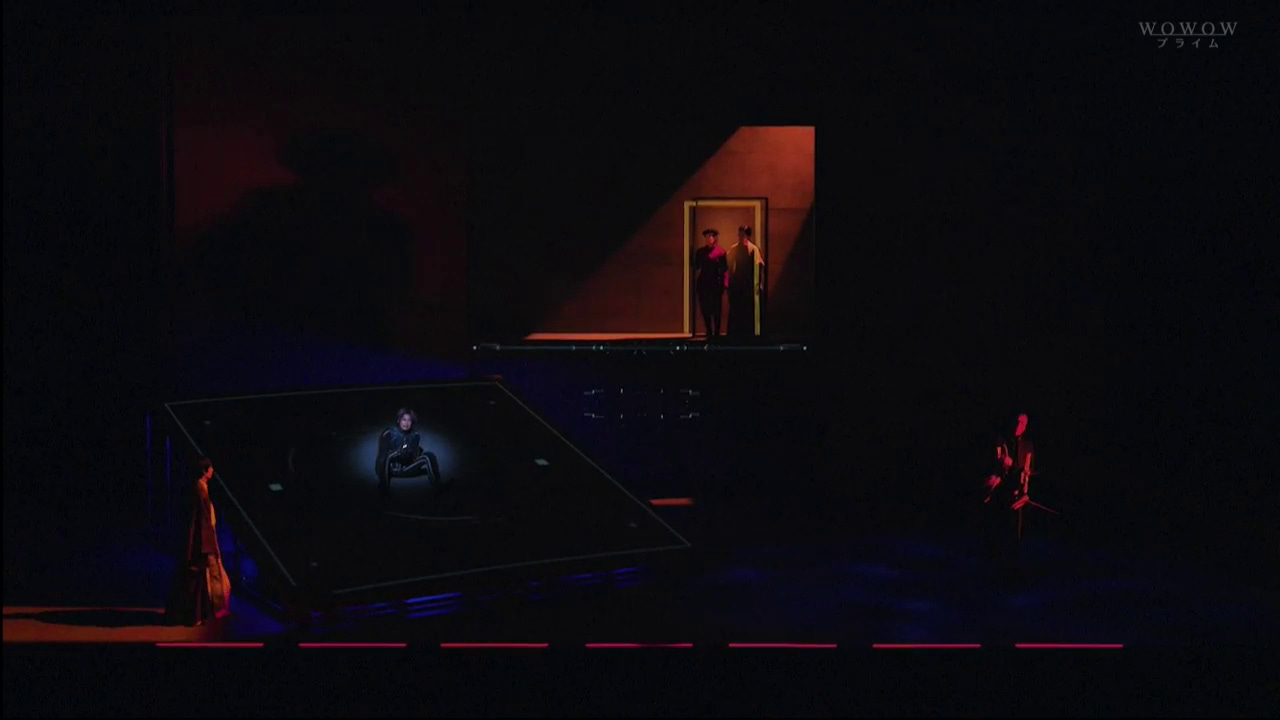

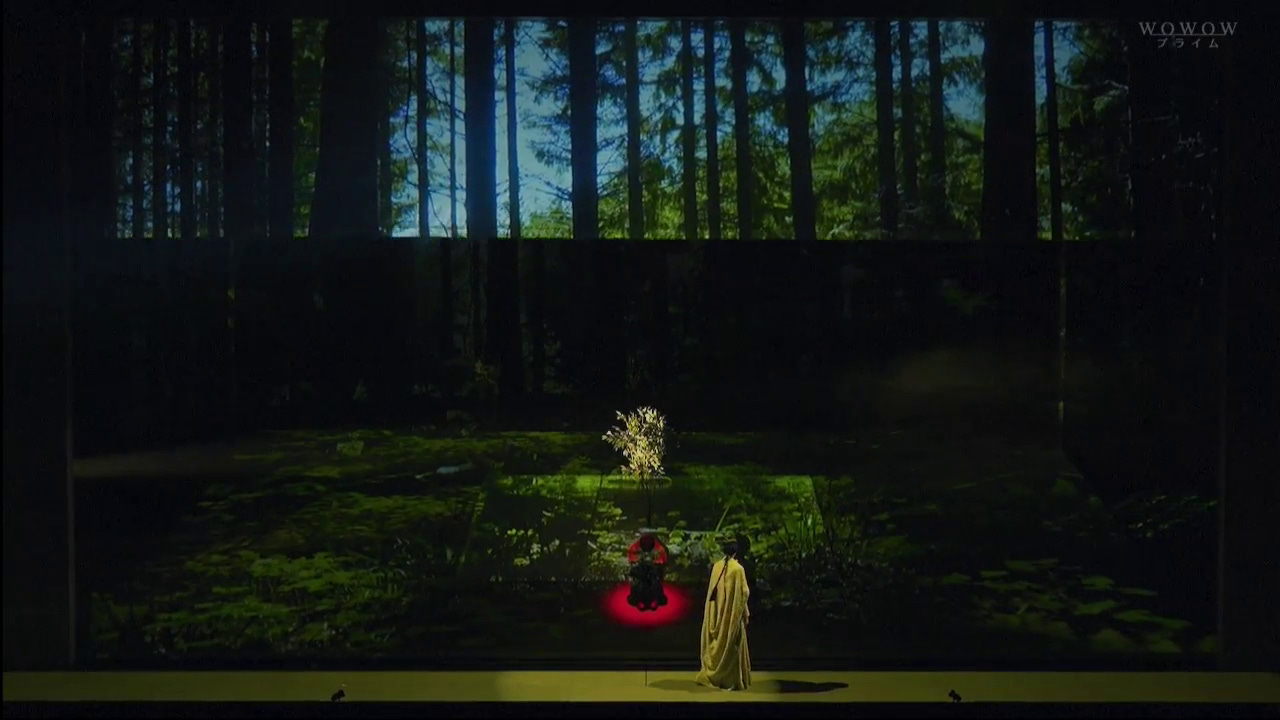

But echoes remain. Watch the brash, hot-headed girl shout “Are you an idiot?”; see the interpersonal relationships—the cold father, the past lover returning, the two young boys in love; witness the apocalyptic conclusion as internal emotions turn physical and become the universe. The ghost of Evangelion can be felt everywhere here. It is like a reincarnated spirit, guiding the play with memories of a past life half-forgotten, déjà vu and an unexplainable familiarity bubbling up at every turn.

It makes sense. Evangelion Beyond is a story of ghosts after all.

For as long as I’ve lived in Japan, I’ve lived in towns devastated by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Drive far enough and watch the buildings fade to nothing but empty wastelands and perpetual construction; drive far enough and find the sea blocked off by giant concrete walls, beaches closed, unknown if they will ever open again. Go to work and every few months see a man walking around the building with a bizarre machine, measuring the radiation levels. Meet people young and old and know that ghosts live all around them.

Evangelion Beyond feels very much like a story about the aftermath of that disaster that is nearly as old as its protagonists. It is about the collective trauma and displacement experienced by a generation who lost their homes and families and possessions and lives in an instant.

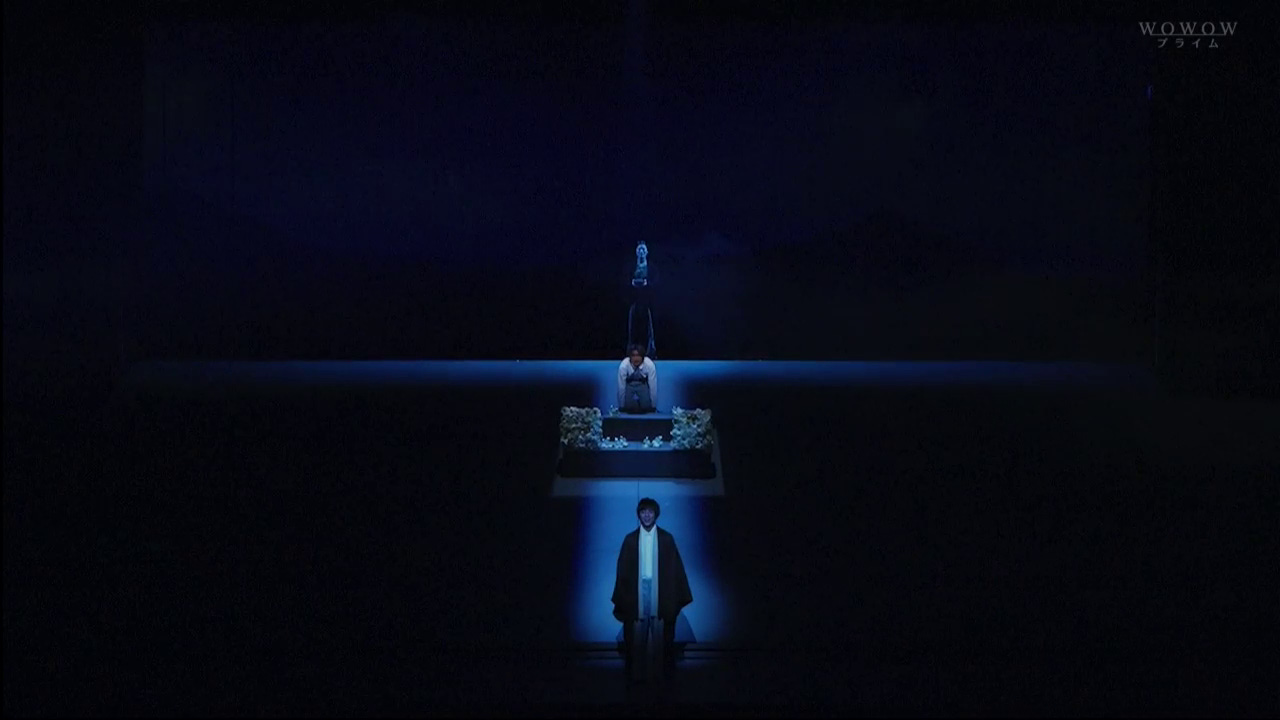

In one of the biggest, most destabilizing twists on franchise expectations, Touma—this story’s analogue to the original’s protagonist Shinji Ikari—vanishes near the start. They hold a funeral for him, but it is hollow and empty. They never found his body; there is no one to mourn. With the very heart and soul of Evangelion as a franchise ripped away, never allowed to know if he is alive or dead, the rest of the cast is left to float through their lives and relationships and the beats of a plot that has lost its purpose. Like the bracelets around their wrists that cannot be removed, which blink and blare to remind them that they are pilots in an Evangelion story, that they have no choice but to suffer and fight, they have become trapped in a story that isn’t theirs.

How many are living just like them? How many of us are trapped in a purgatory of not knowing, in a world different than the one we are supposed to be in? How many of us are begging for ghosts?

I can never really understand. No matter how long I live here, how many people affected I get to know, the tragedy of 2011 will always exist to me layers removed, abstracted like the news. I can only visit the memorials and see the ages of those lost: fourteen, ten, three. Zero. I can only try to read their names. It's an experience that is enough to break anyone's heart, and yet compared to the truth, it isn't anything at all—just some letters on stone. Language and names could never hope to capture the infinite beauty and potential of each and every person lost.

In Samuel R. Delany’s Tales of Neveryon, a collection of interconnected sword and sorcery short stories, and old woman and a young girl have a conversation. They talk about a lot, about womanhood and societal customs and faith and invention, but above all else they talk about language. They talk about names. What is language if not a collection of names? We see a rock and name it a rock. We see a stick and decide, “Is this also a rock? Or does it have a different name?” And so following this we continue over and over again until the entire universe has been catalogued and categorized and named, until it all is known. Language, the two women decide, is nothing but a mirror. You can see the truth of things with it, but that truth has been reversed and distorted. It is, inevitably, a fundamentally different thing, a tool of order and thus a tool of oppression.

A similar conversation happens in Evangelion Beyond. Soushi, a mysterious man with connections to both the Evangelion Project and the meteor that fell, briefly becomes a teacher for the teenage Eva pilots, and in his first lesson, he talks about birds. You might think you know the name of a sparrow or a finch, but birds are called different things in different languages, meaning and symbology changing from person to person. As such, to know the name of a bird isn’t to know a bird at all. It’s to only know a word. These characters have names different than what the franchise says that they should. Is it a different language? Are they nothing more than mirrors pointed at more mirrors?

Near the end of The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a documentary about Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki is found in a garden. “[Studio Ghibli] is going to fall apart,” he says, as if talking about nothing more important than the weather. “What’s the use worrying? It’s inevitable. ‘Ghibli’ is just a random name I got from an airplane. It’s only a name.” He looks out at the flowers and the trees and sky. “How pretty.”

Evangelion Beyond has been met to divisive reactions. Some see it as being too connected to the original series, others not enough; some find it too vague and some too didactic. Even outside of is narrative, it is a franchise in flux, both dead and alive. It is like its characters and its characters are like us, a reflection of a reflection of a reflection. In that sense, it couldn’t be more Evangelion if it tried.

On the anniversary of the earthquake and tsunami, at exactly 2:46 PM—the same time of the earthquake—I stood along with everyone else and faced the sea in silence as an alarm blared, and when it was over, a woman came to me and said, “Be careful. There are a lot of ghosts out today.”

When I looked out the window, all I saw were empty streets.

What is Evangelion?

It’s only a name.

Music of the week: situasion - Amputasion

Idols are everything. When all of us are gone and buried, earth run its course and sun dying, only idols will remain. Not many prove this as strongly as situasion, who put out one of the best idol projects of last year here: a lean collection of tracks that effortlessly floats through dreamy glitch pop, blistering bubblegum bass, and even a psychedelic exotica pop groove with shades of Afrirampo (a band I love more than anything).

Movie of the week: One Day, You Will Reach the Sea

Beautifully felt drama about the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and how Japan is still very much living in its aftershocks. Quiet and intimate and honest, emotion from the past coming in like waves to disrupt the present. Full of great performances and moments that sneak up and hit you like a truck. Also Yukino Kishii and Minami Hamabe — for my money two of the most exciting young actors in Japan right now — are supremely gay for each other in it, so that’s worth at least like, 20 extra points.

Thanks for visiting! If you liked what you read, share it around! It’d make my day :)

to any Evahead, every word in this paragraph is a disgusting simplification of both Evangelion’s narrative and its place in Japanese culture. I agree! But we ain’t got the time!!! ↩