Talking tv | Atami no Sousakan

Don't call it twin peaks.

I hate comparing things to Twin Peaks. The mega-hit TV series from David Lynch and Mark Frost, which all but defined the future of televised drama, is undeniably hyper-influential—a towering giant in the medium for good reason. But over the years, the show has been diluted to near memetic short-hand, a vague adjective with hardly any meaning left that threatens to reduce any serialized narrative into being "like Twin Peaks." The cast have any oddballs? That's Twin Peaks. It's set in a small town? Must be Twin Peaks. There are elements of surrealism, no matter how trace? Sure sounds like Twin Peaks to me! The comparison frequently (and increasingly) feels both unearned and reductive, an empty platitude that says nothing at all.

I hate comparing things to Twin Peaks, and yet...

Atami no Sousakan is a lot like Twin Peaks. This isn't by accident—from moment one the show makes it clear that it is an overt riff on the classic, first episode filled with callbacks and gags galore, delighting in referencing Lynch's series at every turn. An offbeat agent (from a fictional organization described as being "like America's FBI") who speaks over a headset to an unseen woman, and who uses unconventional, occult-leaning techniques to solve the most difficult mysteries, arrives in a small town full of weirdo sheriffs, seedy underbellies, and comfy diners where the desserts are world class and the coffee damn fine. Director Satoshi Miki is almost goading the audience to make the comparison as he recreates scenes from the show wholesale; to not mention Twin Peaks when discussing it seems borderline irresponsible.

And yet, Atami no Sousakan is also decidedly not Twin Peaks. Not even close. There's no body, for one.

The mystery is a genre seeped in death. The corpse has, since its inception, been an integral component. To have a proper mystery in the eyes of many, there must first be a murder. There would be no C. Auguste Dupin—the first modern detective—if Edgar Allan Poe didn't also invent a murder. There wouldn’t be Sherlock Holmes without a study in scarlet. Likewise, there would be no Twin Peaks without the body of Laura Palmer. But there she is, and the discovery of her body ripples through the town, grief spreading like a disease. There she is, and so the mystery has form and purpose. Because Laura Palmer exists, her murder can be solved; closure is possible.

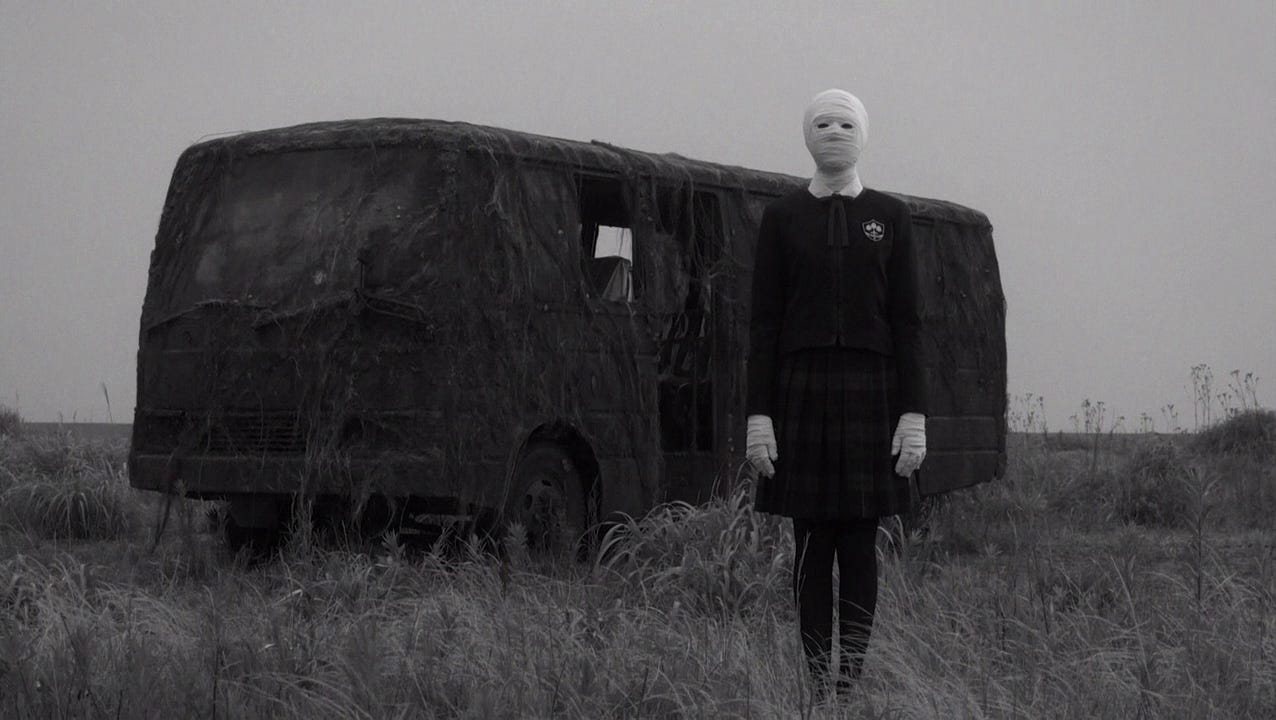

But what do you do when there is no body? What do you do when you aren't even granted the possibility of a conclusion? For the citizens of Atami, they float. After a group of girls attending a private catholic school disappear along with the bus they were riding in, the people living in Atami become trapped in this mystery as if swallowed up by a mist. And no matter how hard they claw and grope, they can’t find their way out. A yakuza group that continuously reinvents themselves in attempts to remind the people of their importance; a police chief who no matter how hard he tries is unable to do anything right, his role effectively useless; a young girl who's dream of being an actress is robbed as the mystery takes over, desperately trying to insert herself into the story and failing at every turn. For years the outside world only sees the town in relation to the girls, and over time their absence becomes the very identity of Atami and everyone living in it, a town trapped in stasis, defined not by what is there but by what is not. It becomes a town populated by corporeal ghosts trying to prove that they exist.

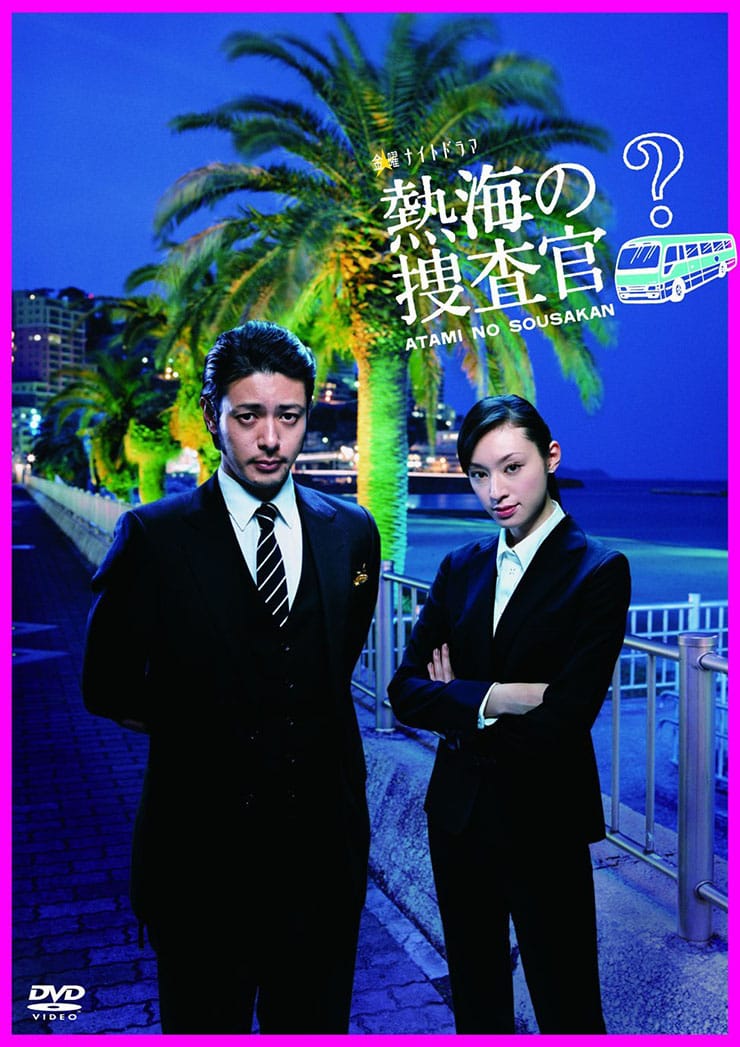

Enter our detective, Kenzo Hashizaki, and his partner, Sae Kitajima. Coming from the outside where lives still have meaning, the two fall increasingly into the dreamy mist of Atami as they grasp for knowledge and understanding.

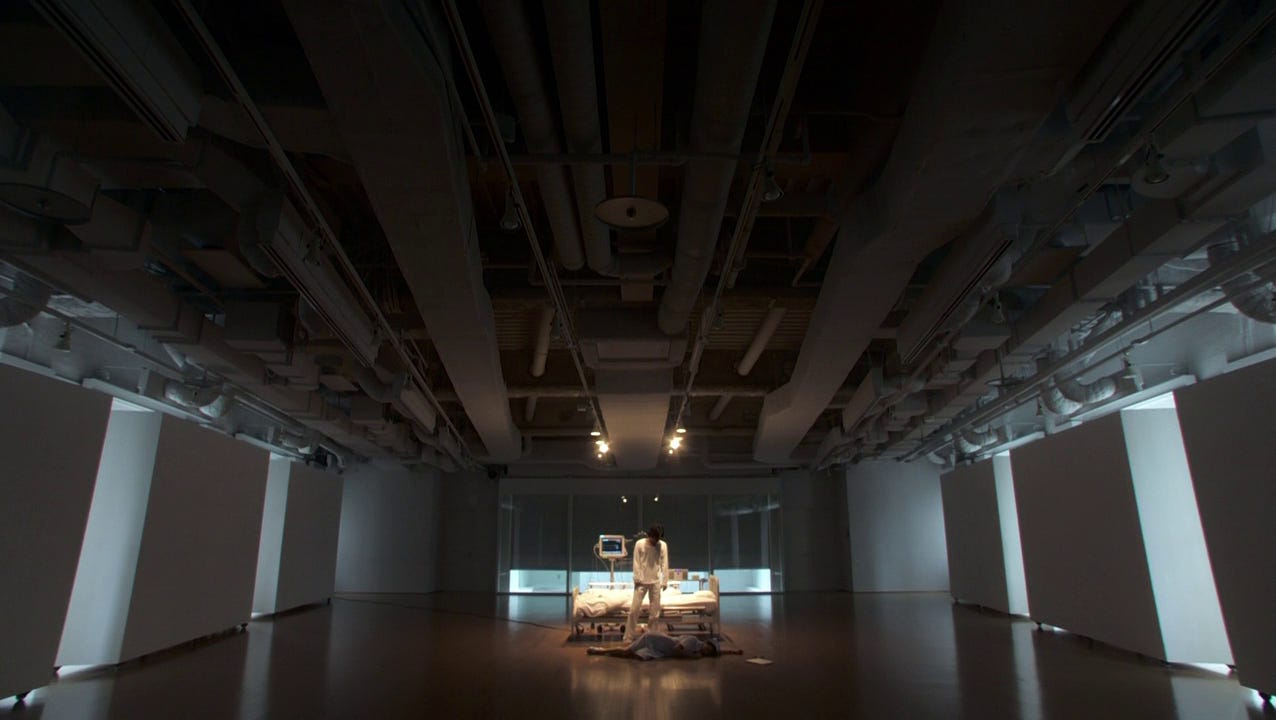

It's not easy. Absurd surrealism is the name of the game in Atami no Sousakan, Satoshi Miki clearly (and self-admittedly) inspired by the dense symbolism of Shuji Terayama and Seijun Suzuki--scenes filled with psychic abilities, gold-colored men, impossible magic shows, and hallucinatory dialogue, much of which goes completely uncommented on. At first it all feels meaningless, weird non-sequiturs for the sake of the equally weird jokes that populate the series at every turn. But as the series progresses, another sense takes root: that maybe all of those jokes weren't jokes at all. Maybe everything has been building to something from the start.

There is a deep desire here, from audience and characters, for everything that happens to be intentional, to have meaning, to make sense. There's a palpable, desperate need for answers.

And that's the problem with mysteries, isn't it. They exist to be solved. Their entire function is to end. They are the most perfect genre reflection of us in that way—us, so insatiable, so desperate for answers and logic and sense, for all of it to connect and tie up in a nice clean bow. Read anything about how to tell a story, listen to any misguided lecture on "good" narrative craft, and you will inevitably be greeted with ideas of leanness, of everything coming together by the end, of everything mattering. "Good stories," you might hear, "have no fat to them. Just look at all these examples. Look how the classics do it. Look at all the blockbusters the world loves."

The Russo Brothers, the directors behind the single most successful film in history, have honed this down to a near scientific equation: the inciting incident must happen on this page, the twist here, the climax there. For many like them, it increasingly seems that if stories were a mystery, then it is a mystery that has been solved.

You can see it in AI, in fundamentally uncurious entrepreneurial techbros who see art as nothing more than commodity, making pretensions of creativity finally being free and accessible while they rob the body parts of a thousand different works to graft them together into some unholy, unfeeling Frankenstein's monster, narrative left as literally nothing more than an unending cavalcade of stolen references and recreations.

"It's like Wes Anderson," they say. "It's like Lynch; like Twin Peaks."

To them, there is no mystery, not anymore. Even a computer can do it now. It's all just science.

But the thing about mysteries and the thing about life is that there isn't really an end to either of them. They come one after another, like a child asking "why?" after every answer. The deeper you dig, the more they all stack and connect and melt together until the reality makes itself clear: that it is impossible to ever really hold the truth, that you will always be floating in the mist.

In one scene, Kenzo and Sae visit a famed mathematician to see if he can make sense of the strange and complex equations found in the notebook of one of the missing girls. He tells them to come back in two days. When they do, they find him in a room covered in numbers. He has lost his mind. He tells, through shouts and tears, that there are some things that shouldn't be known, that can't be known. Defeated and hollow, he gives them the book back and begs them to give up on it.

Of course, they don't. They have to know.

I hate comparing things to Twin Peaks. It's easy and reductive and frequently wrong. But despite it all, I do it anyway. I compare and compare, to Twin Peaks and to Lynch, to Terayama, Suzuki, Poe and Holmes, to titles and genres and ideas and myself.

I'm only human, after all. I just want it all to make sense.

Music of the week: Shintaro Sakamoto - Like a Fable

Shintaro Sakamoto makes music that sounds like plastic neon palm trees. Borrowing heavily from the sound of artists like Haruomi Hosono in the ‘70s, he plays mad scientist with almost impossibly catchy, laid-back and tropical soft rock, injecting his own weird sensibilities deep into the blood. The result is a collection of all-time good vibes tunes that feel just a little off, like a nice and charming neighbor who has weird noises coming from their basement in the middle of the night.

Movie of the week: Grass Labyrinth

Shuji Terayama is about as important and influential an artist as you can get, and Grass Labyrinth is one of his many masterpieces — a lightning quick and hyper-surreal psycho-sexual drama played out while JA Seazer blasts some absolute avant-prog freakouts in the background. Confrontational and aggressively interior and chock full of some of the wildest, most indelible imagery you’ll find in movies; a real pandora’s box of uncomfortable truths you can spend a lifetime unpacking. Perfect Freak Cinema.

Thanks for visiting! If you liked what you read, share it around! It’d make my day :)