Talking games | The NSFW History of Strip Mahjong Games

A story of sex, politics, and the games that once ruled arcades

CONTENT WARNING: The title isn't a joke, this article is extremely NSFW, continue at your own risk (you will see so many digital boobies, I swear to God)

The year was 1983, and Nihon Bussan was panicking. Beginning as a jukebox rental company in 1970 created by then 23 year old Sueharu Torii before pivoting five years later into the burgeoning video game arcade scene, the company had, in those years, managed to earn itself a less than sterling reputation. Though responsible for several innovations in the field and multiple hit titles like Moon Cresta and Crazy Climber, along with an early example of an adult game with the nudity filled puzzler Frisky Tom, they were also copycats, liars and thieves; a business unashamed in their corporate greed.

In 1978, they had successfully earned the ire of industry giants Taito after publishing Space Invaders clone, Moon Base, without paying a licensing fee. The next year, they found similar trouble with Namco, continuing to produce their clone of Galaxian, Moon Alien, past the agreed upon number of units. Despite this, Nichibutsu, Nihon Bussan’s main game division, had no qualms claiming either game as completely original products and properties. And they were aggressively protective of their own property, chasing after any perceived copyright infringement and infamously resulting in an ominous message published to other companies in industry magazine Game Machine, warning everyone to be careful with how they treated Nichibutsu products.

But by 1983, the tough act had caught up with them. With their last several games severely under-performing, and the company deep in the throes of their largest project to date, their soon to be disastrous entrance into the home console market, the MyVision, Nihon Bussan was desperate for money. They needed success, and they needed it fast.

Their solution was cheap and desperate, an obvious grab for a quick buck to save a previous failure by a floundering company. And it would change the course of Japanese gaming almost overnight.

This is the story of the game that saved Nihon Bussan, and the industry it birthed. It is a story of politics, ethics, capitalism, and the very history of arcades themselves — all of it coiled tightly around the naked flesh of a digital woman, smiling expectantly on the other side of the CRT.

This is the story of strip mahjong.

ONE

More than one hundred years ago, in the newly established Odomari Junior High school located on the island of Karafuto, now Sakhalin, a game was played. It would have been after classes had finished, likely late into the night, the teachers huddled together around a single table. Only one knew how to play the game; the man who had brought it to them in the first place: Hikosaku Nagawa, returned to Japan in 1909 after a four year stint teaching English in China — though it is possible others had heard of it in passing through Nagawa’s former university teacher, Natsume Soseki, in his serialized travelogue Travels in Manchuria and Korea.

The game, played similarly to poker but with thick tiles, where players take turns trying to compose high-scoring hands through draws and discards, was initially daunting; but as the various rules and hands became clear, it revealed itself to be almost unnaturally addicting; an intoxicating blend of gambling, chance, social engineering, and pattern reading — all while sitting around the same small table, enjoying each other’s company and conversation.

The name of the game that enraptured the teachers? Mahjong. And it was about to take Japan by storm.

Nagawa saw it as his mission to spread mahjong wherever he could, continuing to teach it to colleagues and students in his spare time. Not that he had to try too hard to accomplish his goal. It’s very unlikely he was the only one who had brought the game back, and it was an instant hit with everyone who played it, mahjong rapidly taking over the country. In 1929, only twenty years after he had returned to Japan, Tokyo held their first national mahjong tournament. A year later, and nearly 1000 dedicated mahjong parlors were in operation across the country, forcing national police to ban the establishment of more parlors in an effort to curb its unstoppable rise.

As World War 2 came and went, the country recovering, mahjong experienced its second surge in popularity with the emergence of a new style: riichi mahjong.

Borrowing elements from Chinese and American rulesets, riichi mahjong introduces a new way to score accomplished through a small pre-emptive bet and a bold declaration of victory when one tile away from a completed hand. While on its own not worth much, declaring riichi acts as an incredibly quick way to end a round, and easily compounds itself on top of other, higher scoring hands. This, in addition to other changes such as special high scoring tiles, makes riichi mahjong a remarkably complex game of deception, aggression, and defense — a game as much about bluffs and reads as it is tile management. And like all the best games, it is one overflowing with its own narratives.

That narrative potential was not ignored by the public as movies and comics all about riichi mahjong released with increasing rapidity as it solidified itself as the definitive version of the game in Japan. Professional groups, annual tournaments, and televised matches only continued to grow until, in 1981, riichi mahjong finally made the leap to the electronic with Janputer. The first mahjong arcade game ever produced, Janputer utilized a flat, table style cabinet perfect for emulating the real thing, almost immediately becoming a fixture of cafes across the country, ushering the classic game into a bold new world.

But then, Nihon Bussan didn’t care about any of that. They didn’t have the time or money to enjoy the luxury of history, because their entry into the new land of mahjong arcade games, Jangou, had just flopped. Truthfully, it didn’t have much chance to do anything else. A visually rudimentary adaptation of the niche Buu style of riichi mahjong, the game simply lacked any appeal to a broader audience already satisfied with Janputer, and seemed destined to become nothing more than another forgotten machine in the corner of failing arcades, collecting dust until its name can no longer be read.

And if that happened, there was no doubt that Nihon Bussan wouldn’t be far behind, fading into nothing more than an obscure footnote in gaming history. Unable to tank the failure and try again from scratch, the company quickly ceased production of Jangou and ran back to the drawing board, desperate to find some fix, some change to the game that could save it from its predetermined fate.

It didn’t take long for the answer to show itself — a solution as tired and true as they come; the kind so obvious, so primordially simple, that it could only be thought up by a group of capitalist hungry men.

They put a naked woman in it.

Trapped in a window one-fourth the total screen due to technical limitations, a drawing of a woman in a bunny girl outfit is forced to strip, removing one piece of clothing for each win from the player until, after five consecutive wins, one is allowed to gaze fully upon her pixelated flesh. With little else changed but a new title, Jangou Night was released upon Japan only a few months later.

It was unquestionably a crass, cheap move screaming desperation. It was also an overwhelming success.

In no time at all, Nihon Bussan found themselves not just saved from financial ruin, but thriving. People could not stay away from their game of simple sensuality. And answering the populace’s desires, smelling money in their blood, Nihon Bussan immediately shifted game development to almost exclusively adult games; in particular, mahjong.

Of course, strip mahjong had already existed in some capacity — never underestimate mankind’s talent for getting naked — through claims of female swindlers undressing to distract opponents or betting clothes at parties and in drunken reveries, but it had never before been clearly defined or recognized by the general public. By all accounts, Nihon Bussan’s quick conversion of their own game represents the birth of the images that flow through the mind when the words “strip mahjong” are spoken.

Striking while the iron was hot and sweaty, Nihon Bussan would release a second strip mahjong game in the same year, Night Gal, and the year after, two more: Night Bunny and Jangou Lady. As expected from such a rapid development cycle, the games were largely lacking in innovation or ambition, their focus instead on presenting new girls to undress. And why shouldn’t they have been? People were not coming for mahjong, they were coming for the novel titillation of it all, for the softly illicit pleasures of earning a peek at a drawn woman. And it was a field Nihon Bussan owned.

But these erotic games were not being played in secret — other companies were paying attention to Nihon Bussan’s success. The day after Christmas, 1984, Video Systems Co. split from their parent company Visco to become their own independent publisher. The first project of the new group arrived that next year; a strip mahjong game with the name Lingerie House. Another player had joined the table. Things were about to get busy.

And while others entered into the game, beginning a battle for the throne Nihon Bussan sat on, a young Tatsuda Yasushi sat down at one of the many strip mahjong tables with his friends in a Shinjuku arcade, blissfully unaware that, in a few short years, he would shape the future of the genre with his own hands.

TWO

It’s hard to imagine any Japanese programmer not being familiar with Hot Soup Processor. A freeware programming language in Japanese released in 1994 by Onion Software, Hot Soup Processor (abbreviated HSP) is nearly an institution in itself. Long used to teach programming in schools and as a common first language for self-learners, HSP also quickly established itself on release the language of choice of doujin (Japanese indie) games thanks to its ease of use and its irresistible price of ‘free’.

But sitting at that arcade table with his friends who together made up Onion Software, Yasushi, also known as Onitama, was far away from any thoughts as lofty as redefining Japanese coding. Back then, there was only one thought running through his mind: strip mahjong games suck.

After all, Onitama barely knew a world without mahjong. It had always been there; lifelong relationships between friends and family born around the mahjong table. A lot can be learned of one another through a game of mahjong; everyone facing one another, shuffling tiles together, talking and planning and lying. And strip mahjong games lacked that magic. There was no character to them, no life. The AI was bland, turning every opponent into the same anonymous player, and the women little more than lifeless dolls waiting to be undressed. There was no ambition, no humanity.

It was then, after bemoaning the failures of the genre and wondering why a strip mahjong game hadn’t made its way to home computers yet, that Onitama’s friend, artist E.NAO, posed a simple question: why didn’t Onitama just make one himself?

In the early ‘80s, doujin game and software development was still in its infancy, the few doujin circles (independent teams) active largely producing simple puzzle games and early pixel art image collections. Owing to hurdles technical, financial, and otherwise, the idea of a fully featured doujin game was remarkably ambitious. And Onitama was anything if not ambitious. Accepting E.NAO’s challenge, he set to work, determined to make nothing less than the greatest mahjong game ever seen.

The secret, he believed, was to capture the same feeling that had defined so much of his life into the digital; the sense of connectedness and awareness of the unique idiosyncrasies that define us felt while around a mahjong table. But mahjong is a game of secrecy, and being well before usable internet, multiplayer on a home computer was not feasible, meaning that this living experience had to be captured through the decidedly non-living AI.

To accomplish this, Onitama made each opponent a distinct character, all based on his friends and all featuring their own unique playstyle. “Tanayo Tacchan” will do anything for a tanyao (a winning hand made using only tiles numbered 2–8); “Power Tsumo OXYGEN” — named after the soon to be designer of the game’s logo — was preternaturally lucky at drawing ippatsu tsumo (drawing the winning tile within the first turn of calling riichi). By giving everyone a gimmick, every character’s playstyle became remarkably recognizable, radically changing how the player might approach a game. Suddenly, just like in real life, play needs to be altered to match the opponent, ebbing and flowing between offense and defense, the silly personalities turning the previously cold and empty digital mahjong into one full of warmth, color, and life.

But with radically unique playstyles, the digital opponents also pushed against the rules of mahjong, blatantly cheating and altering tiles for their own advantage. Just as even a professional can’t win against a stacked house, there was no hope for the player. So, Onitama did the simplest thing in the world. He let the player cheat, too.

With points earned through strong play, various abilities and advantages can be purchased, such as exchanging one tile in a hand for another, effectively giving the player an even greater advantage, tipping the scales in their favor and transforming the game’s mahjong into something wholly different — a chaotic, unorthodox experience impossible in the real world.

Adding a deeply silly story packed full of in-jokes, Onitama shared his progress with friends and, bolstered by a positive reception, asked E.NAO to draw the main character who would fill in the large swaths of black dominating the screen and transform the mahjong adventure — which had been christened with the portmanteau name Majaventure — into a true strip mahjong experience.

By and large, games of the time shied away from a more aggressive anime aesthetic, strip mahjong in particular favoring artwork with relatively natural proportions and less exaggerated features. This left anime to doujin artists like E.NAO. Favoring the recent lolicon style, E.NAO’s characters were hyper-deformed and exaggerated, looking as if they still had their baby fat and resembling what is now considered “chibi”. It was a look unheard of in larger gaming circles, giving Majaventure a distinct, appropriately silly aesthetic to match its mad-cap style.

Of course, the industry wasn’t simply twiddling its thumbs while Onitama and E.NAO were putting the finishing touches on their game. Strip mahjong games were only becoming more common, releases hitting arcades at an ever increasing rate with many, like Onitama, trying to leave their mark on the young genre; perhaps none more significant than 1985’s Real Mahjong Pai Pai.

Developed by Alba, who were really the newly formed Seta under a different name, and published by Taito, Real Mahjong Pai Pai attempted to differentiate itself from the pack via an increased focus on realism. In stark contrast to Majaventure’s fast and loose relationship to rules, Real Mahjong Pai Pai aimed for grounded, accurate mahjong both mechanically and visually, represented though its groundbreaking presentation of tiles as 3D objects. The game also served as an early title focusing on two player mahjong, a style that would soon become standard in the genre due its faster and more arcade appropriate dynamic.

Real Mahjong Pai Pai, whose impressive depth in tiles and shadows far outshines the stripping.

Meanwhile, other companies were keeping a close eye on Onitama’s work. A few days after selling Majaventure at a doujin convention, Onitama received a call from Tokuma Shoten Publishing, the company who produced the Sweet-88 development software he had used to make the game. He felt the blood drain from his body. Not only had never received the required permissions to use the software, but he had just made a profit from it. He was in deep trouble.

But summoning the courage to ask what they wanted, Onitama received an answer nobody could have imagined: they were interested in selling his game. This was unheard of — a major company not only promoting but actively supporting a doujin game creator — and represented a major shift in the world of tech’s relationship to doujin as Tokuma Shoten provided Onitama with a modest budget to further fine-tune the game until, on October 2, 1986, two years after that night he sat down in an arcade, Majaventure was officially released to the world for the PC-8801. A wild, free-wheeling comedy adventure deeply in tune with otaku media, bursting with personality and a unique, distinctly video game approach to mahjong, Majaventure blew every previous attempt of the genre out of the water, emerging as a shining beacon not only of the potential of mahjong games, but of doujin games as a whole, influencing and defining the shape of nearly every strip mahjong game to come. Onitama had done exactly he what he had set out to. He had made the greatest mahjong game yet.

THREE

By 1987, strip mahjong had successfully established itself as an arcade mainstay, one or more of the salacious tables all but a given in any arcade worth its salt.

In the face of countless competitors entering what was once exclusively their market, Nihon Bussan’s output began to twist and change, experimenting more and more within the strip mahjong space, and none more significantly than Second Love. On its face just drop in the lake of games with quick, rudimentary, pixel art strip scenes, Second Love’s contained another side to itself, one that had never been seen in the genre: real people.

The two sides of Second Love. Source: https://aucview.aucfan.com.

Allowing the player to freely choose between real photographs and drawn adaptations of the same scenes, Second Love’s effect on the landscape was devastating; erotic dreams made real, hidden under the haze of low resolution video tapes. The game was an immediate success, ushering in the age of a new kind of strip mahjong: video mahjong. Using generically designed mahjong games as a base, video mahjong cabinets include various video players in their guts, allowing arcade owners to simply replace the video for a new experience, a canny design decision deeply attractive to arcade owners. Never one to drop potential profit, Nihon Bussan began splitting their mahjong game production between drawn and live-action, crowning themselves the king of both worlds.

But where Nihon Bussan found success in embracing the real, Seta found trouble. Their Taito published, 1987 release, Super Real Mahjong PI — taking its title and concept from their previous effort two years earlier as Alba — had bombed. The issue was simple: while the game featured groundbreaking work in capturing the true mahjong experience, with lovingly detailed tiles, a deep ruleset, and nostalgic flourishes such as hands shuffling tiles between rounds, that’s all it was. There was no nudity, no stripping, no character.

Playing out like a replay of the desperate move from Nihon Bussan than created the genre, Seta took the game back and slapped some nudity on top, rereleasing it as Super Real Mahjong PII that same June. Unlike their forefathers however, PII was anything but cheap.

Using a decidedly anime aesthetic animated by industry veteran Ryo Tanaka, whose credits include perennial classics like Fist of the North Star, YuYu Hakusho, and Lupin the Third, Super Real Mahjong PII looked like nothing else on the market; its character sprites big and clean and full of personality in their movements and looks. And Seta didn’t stop there, PII being the first adult game to feature professional voice acting via Yuriko Yamamoto, imbuing the main character with life and charm previously unknown. A sense of budget and polish rare in adult games permeates the experience; a confidence in its own self-evident quality oozes from its every inch.

Compared to its contemporaries, Super Real Mahjong PII was like playing a Hollywood blockbuster in a sea of home video. Parallels to the birth of the genre continuing, the game was a monumental hit, going on to see a host of sequels and becoming the unquestioned face of strip mahjong — a title it still holds today.

The next year, eager to topple Super Real Mahjong PII’s blockbuster status, mysterious company Yuuga released Mahjong Gakuen. Just like Super Real Mahjong PII, Mahjong Gakuen was a game of almost shocking quality, with gorgeous, distinctive artwork of realistic, fashionable women, a big, clean UI, and surprisingly intelligent AI that took cues from Majaventure’s power-up system. But all of that paled in comparison to the game’s true selling point and what would become its ultimate legacy: a button.

Mahjong arcade tables typically operated with a series of buttons running through the letters of the alphabet, each corresponding to a tile in the hand. Press A and discard the tile in the A position. Same for B, and C, all the way to N. But there was something different about Mahjong Gakuen’s H-button. Mashing the H-button, and only the H-button, at the proper time during one of the many stripping scenes, and disembodied hands emerge to grope the women; skin pulled, pushed, and spread. Suddenly the soft sensuality of strip mahjong became explicit, the presence of a second party transforming the passive active. Things were no longer about stripping — they were about sex.

Mahjong Gakuen sold an estimated monstrous 17,000 units, influencing competitors to similarly push sexual boundaries and include a new use for the lowly H-button. But without any other games to their name, the question remained: who were Yuuga?

Turning away from the simple sensuality of previous titles and embracing sex, the hands that emerged within Mahjong Gakuen (read as Mahjong Academy) were a shock to the system.

It was not uncommon during the ‘80s and early ‘90s for game developers to publish titles under different names. Frequently, this was to hide games they might not want associated with the brand — such as adult games — but could also be seen used for rushed jobs, licensed titles, or a host of other reasons. This applied to Yuuga, the cover name for a small group working in one of gaming’s biggest names.

That name? Capcom. And Mahjong Gakuen’s development team represented a powerhouse group on the precipice of becoming gaming legends.

Like Onitama, lead designer and producer Okamoto Yoshiki — developer of Konami classics Gun.Smoke and 1942 — was disappointed with the state of mahjong games and their lack of ambition or quality, and was convinced he could do better. Capcom, at the time at a financial low-point and wary about developing an adult game, granted his convictions only a small core team, an even smaller budget, and many sleepless nights, the game noticeably left missing from their official development schedule. Not that any of that would stop Yoshiki.

When models were needed as reference for the stripping scenes, Yoshiki and the artist he had hired — a young man calling himself Akiman — would convince female employees to pose for photos in swimsuits. When voices were needed, they’d call the same women and provide their own voices for the men, a practice repeated in the iconic Street Fighter II, developed by largely the same team. Indeed, the AI system developed for the game would later serve as the basis for the fighting game’s computer opponents, along with enemies in other titles like Final Fight. Even the soundtrack was left to a legend in Tamayo Kawamoto, who had already become a major name through her work in games like Commando and the perennially iconic Ghouls and Ghosts.

Innovation and talent was overflowing within the world of strip mahjong, its unending stream of successes that could save companies influencing the wider Japanese gaming world in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. There was no question: strip mahjong had entered its golden age.

FOUR

On April 19, 1988, a sea of men in black business suits gathered together in a room. They represented the most powerful names in the business of arcades, the people and corporations who controlled the industry and decided what direction fate would turn, and they had met for a single purpose: to discuss a game.

Founded in 1981, the Japan Amusement Machine and Marketing Association (abbreviated JAMMA), represented a massive play for ensuring the success of the growing arcade scene. A trade association composed of nearly every major games company at the time — Sega, Taito, Tecmo, Capcom, Konami, and Nintendo for a time included among innumerable others — JAMMA concerned itself entirely with the mutual benefit of all companies in mind; a group dedicated to ensuring continued capitalist expansion.

Mostly this ensurance came in the form of various production standards such as universal wiring for arcade cabinets to allow for games to be easily swapped out for another, or approved video players to simplify potential malfunctions and increase copy protections. But arcades are not just machinery — people fill the business like blood, and human concerns of morals, politics, and public perception must also be considered else the industry rot and become a corpse.

JAMMA had no choice then, but to tackle the increasingly explicit scenes found in strip mahjong. Anybody of any age could walk into an arcade and play these games of objectifying nudity, and companies were concerned this would birth negative attention from the public, potentially resulting in declining sales for the industry writ large. However an outright ban on nudity and sex was unthinkable to JAMMA. Adult games were simply too lucrative for everyone involved to stop. To them, it was simply an issue of boundaries. Partnering with the All Nippon Amusement Machine Operators’ Union (or AOU) — a group similar to JAMMA focusing on the businesses that owned arcades — JAMMA requested all participating companies refrain from selling, creating, or distributing games that might be vaguely defined as overly illicit. This was especially pointed towards strip mahjong.

The game that brought JAMMA together and caused them to act was never publicly named, however in a document distributed to developers and manufacturers on June 24, it was noted that the association’s concerns were raised due to one where disembodied hands could emerge and touch naked women with the press a single button. An H-button.

In the aftermath of JAMMA’s new decency standards, Nihon Bussan continued as usual, their unending stream of titles turning increasingly conceptually absurd.

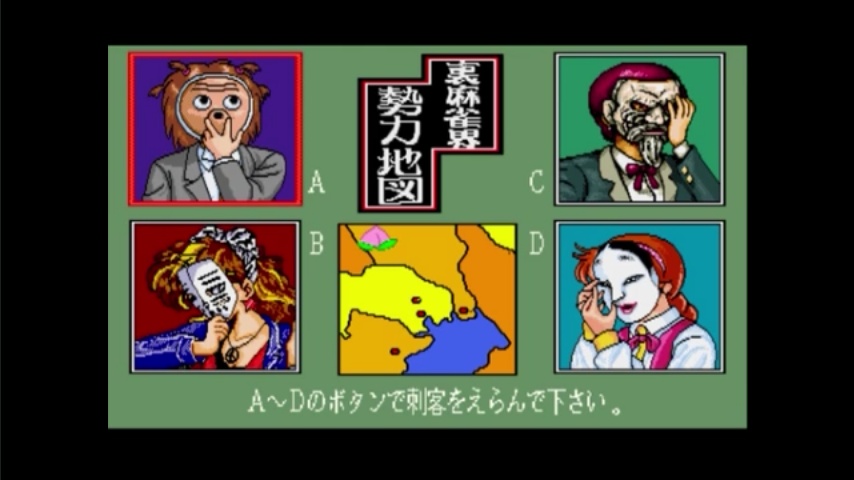

Mahjong Shikaku, where the player must defeat the mahjong underworld’s strongest assassins, who all look suspiciously familiar.

1988 saw the release of Mahjong Shikaku, the first overt parody strip mahjong game, featuring barely disguised characters from various franchises. Naussica, Ranma 1/2, Urusei Yatsura, Minky Momo…all of the most famous anime girls gathered together, eager to get naked for the player. A few months later and a spin-off, Mahjong Shikaku Gaiden — Hana no Momoko Gumi, focused exclusively on then hit sukeban (female delinquent) manga Hana no Asuka-gumi would also release. Understandably big successes, Nihon Bussan found themselves with another sub-genre of a sub-genre to mine, putting out several more parody games over time, such as the Batman adjacent Mahjong: The Lady Hunter.

Mahjong Shikaku Gaiden — Hana no Momoko Gumi is less madcap than it’s predecessor, but is also a more considered work of parody.

At the same time, bootlegs for arcades and the home market were rapidly spreading, companies like Hakka International circumventing the Nintendo Famicom’s famous license requirement to stealth release their own clones and adult games to the console. Perhaps the most famous example of these came in the form of Mahjong Kaguya-hime, developed by Nihon Bussan’s Nichibutsu, but published by MIKI. As the name implies, Mahjong Kaguya-hime, loosely based on the famed fairy tale, sees a young woman in traditional garb take center stage, a rarity in the genre. According to Miki, the game was a massive success in China, with around 400,000 boards distributed around the country at its peak. The only problem was that nearly all of them were illegal bootlegs. And with so many flooding the market of a neighboring country, it was inevitable that illegitimate copies wound up in Japan as well.

Not that it bothered Nihon Bussan too much, who managed yet another title in 1988 with Mahjong Satsujin Jiken, the first murder mystery strip mahjong game. By all accounts a standard entry to the genre but with a light detective story layered on top, the game of crime and sex was also the first from the company to showcase the effects of JAMMA’s pressure, characters mysteriously missing nipples, their naked bodies as smooth as a doll’s.

Though perhaps this newfound modesty was simply a one-off event, because the next year they released AV Mahjong — Video no Yosei, a video mahjong game where real AV (adult video) actresses were used as models. JAMMA and the AOU were not happy. Not only was the game far too explicit, especially given its live-action nature, but Nihon Bussan had used a non-approved video deck for the machine, showing an even deeper disrespect towards the association. When the video segments finished playing for a JAMMA meeting and the board was asked what moment was deemed an issue, the response was quick and unanimous: “With the exception of the very beginning, everything is a problem.”

At the same time, the sequel to Capcom’s famed problem child, Mahjong Gakuen, was released — Mahjong Gakuen 2 — Gakuen-cho no Fukushu. With more plot, more characters, a new aesthetic, and a semi-open map allowing players to choose the order of their opponents, the game expanded upon every aspect of the first but one: there was no special button to press anymore, no groping hands or implications of sex.

Though lacking in its predecessor’s extremes, the game would be used as the base for the historical 1989 title, Mahjong Gakuen Touma Soushirou Toujou on the PC Engine, the first non-doujin, officially licensed strip mahjong game to make its way to home consoles. This console entry into the series saw the birth of a feature that remains a staple in adult games today: by pressing the select button, the game immediately pauses and switches to a dummy screen mimicking a generic RPG, saving the player the shame of prying eyes.

However, due to featuring exposed female nipples and home consoles holding stricter standards towards sexual content than arcades, a second printing of Touma Soushirou Toujou was never approved, the game instead receiving a rerelease with the added MILD subtitle, matches stopping before they ever reach any dangerous levels of undress.

Mahjong Gakuen Touma Soushirou Toujou's fake game screen, expertly hiding its horny contents with the definitely very convincing text “AAAA discovered Engaku Janmar”.

And then, after a long back and forth, on February 2, 1990, two years after AV Mahjong — Video no Yosei’s release, Nihon Bussan gave in and officially pledged to do better in supporting JAMMA’s policies.

Later that year, JAMMA, AOU, and the NSA (Nihon Shopping Center Amusement Park Operator’s Association) were approached by Japan’s National Police Safety Division with concerns about strip mahjong; in particular, the accessible nature of the games. Families and children exposed to explicit, uncomfortable images just by stepping foot into an arcade. Without much choice, all three organizations agreed to up their regulations even more, urging their companies to be careful with what they showed in their games.

In response to their pleas, Nihon Bussan released LD Mahjong — Marine Blue Eyes, and Yuuga — yet another team under Capcom — Mahjong Super Maru Kinban in 1991. LD Mahjong was yet another in Nihon Bussan’s line of video mahjong game to push against JAMMA’s standards with live-action footage, while Mahjong Super Maru Kinban, once more featuring artwork from Akiman, represented the extremes of the animated side. Bringing back the famous H-button, there were not just groping hands anymore; a tongue could lick nipples, a razer shave pubic hair, a mirror fully expose a woman’s uncensored vagina, and a curled up fist ejaculate onto their face.

Tissue Time! Mahjong Super Maru Kinban was shockingly explicit, leaving very little to the imagination.

The associations were livid, trapped in an unending loop of self-regulation as its own members continued to display a complete disinterest in walking the impossible tightrope of the explicit and acceptable.

Mahjong Super Maru Kinban was the last strip mahjong game from Capcom, the company releasing Street Fighter II the same year to a level of success adult games could never even dream of, shedding their need for hidden companies and controversy.

As for Nihon Bussan, the company would officially leave JAMMA in 1992, citing the association’s slow response to video deck related issues, boldly striking out on its own with no regulations to hold it back.

FIVE

In the face of JAMMA’s continued efforts for decency in a rapidly evolving market, other companies began the process of migration to a new world full of potential for the lowly strip mahjong, a world that the association couldn’t touch: the home console.

The original Bishoujo Janshi Suchie-Pai was extremely tame for its genre given its release on the Super Famicom, but is also an absolute visual delight.

Perhaps no game signaled these changing times quite as clearly as Jaleco’s 1993 Super Famicom title, Bishoujo Janshi Suchie-Pai. The first in what would become one of the most enduring and iconic series in the genre, Suchie-Pai boasted a soft, inviting presentation bolstered by iconic character designs from manga artist Kenichi Sonoda, creator of Gunsmith Cats. And though the game would receive an arcade port a year later that enjoyed various improvements (most notably hiring the popular voice actress Mika Kanai), it acted as definitive proof of what Mahjong Gakuen had suggested; that the home market was the perfect home for adult games.

The Sega Saturn in particular, arriving in Japan October 22, 1994, with its loose guidelines for what could be published, quickly became a haven for companies looking to squeeze more from their adult games, a fact obvious to any who have ever glanced through the Japanese Saturn library. Here found ports of every Super Real Mahjong game and a large amount of the Suchie-Pai series among countless others from every company sitting at the strip mahjong table, all drawn in by the sweet scent of profit in the air.

Not that arcades had given up, of course. The same year Suchie-Pai arrived on the SNES, Sammy, Seta, and Visco pooled their talents to create the SSV System, a new arcade board that served as the basis for a slew of strip mahjong games from each company such as new titles in Seta’s Super Real Mahjong series, both of Sammy’s Mahjong Hyper Action games, and Visco’s Lovely Pop Mahjong, a game that managed to snag itself a short radio drama spin-off. But unable to ignore potential sales, these games would all find themselves joining the home consoles trend as the distinction between arcade and console began to shrink.

The stages of undress for one of Taisen Idol Mahjong Final Romance 2’s many girls.

In 1995, Video System put out Taisen Idol Mahjong Final Romance 2, the first mahjong game to feature multiplayer possible on separate cabinets, taking influence from contemporary fighting games, a fact cutely referenced in the fighting game-esque subtitle bestowed upon the game’s expanded rerelease, HYPER EDITION. For the first time in a long time, humans had returned to mahjong.

While the genre began to evolve, Nihon Bussan, facing increasing irrelevance since their separation from JAMMA, officially ended production of all non-video mahjong games in 1996, funneling their focus into laserdisc and CD, hopeful that regular updates of new footage and the cheap cost of purchase would result in a consistently returning audience.

Famed shmup developer Psikyo put their own foot in the game in 1997 with Taisen Hot Gimmick, a characteristically chaotic strip mahjong experience packed with loud humor, absurd characters, and gorgeous artwork by Psikyo mainstay Tsukasa Jun. An unquestioned success, the game would not only receive a console port, but transform into a series, finding homes on Windows, the Dreamcast, and the PS2 over the years.

Taisen Hot Gimmick perfectly carries the silly, loud, and cool energy Psikyo is known for.

And 1998 saw one of the most infamous mahjong experiences make its way to the Playstation and Saturn: the Gainax developed Shin Seiki Evangelion — Eva to Yukai na Nakamatachi. A mahjong battle royale between Hideaki Anno developed Gainax properties — Evangelion, Nadia, Gunbuster — the game was a joyous fan service celebration, reveling in these disparate characters interacting around the table. But, though it was absolutely packed to bursting with fan service, it was not a strip mahjong game. There was no undressing, no nudity, no hint of sex.

For a moment, at least. The next year stripping would be added with the PC edition of the game, Shin Seiki Evangelion — Eva to Yuaki na Nakamatachi Datsui Hokan Keikaku! And not just regular stripping — Datsui Hokan Keikaku! offers the rare opportunity to strip male characters as well. Interestingly, perhaps due to shared ownership between Gainax and NHK, the characters from the Nadia franchise, while present, are not included in the strip mahjong mode.

Shin Seiki Evangelion — Eva to Yuaki na Nakamatachi Datsui Hokan Keikaku!, a game full of fun, lingerie, and sexy pics of Gendo Ikari in his undies.

Things were moving fast for the genre. Between high quality new releases and a deep backlog to bring to consoles, it seemed that strip mahjong had finally found its balance; a steady stream of profitable titles perfectly standing between their sexual nature and audience acceptability that could comfortably exist in the expansive world of gaming.

Nobody had any way of knowing that the wire they balanced on was about to be cut beneath their feet.

SIX

It began a few years earlier in Stockholm. The inaugural 1996 World Congress Against Sexual Exploitation of Children and Adolescents was being held, and Japan was in the hot seat. Signaled out as a major producer of child pornography, the congress, which held seats for nearly every major country, reamed into Japan, spending further time examining the commercialized sexual exploitation of children by business for entertainment and profit. Under-aged gravure, lolicon art, the status of school uniforms as a sexual object, their representation in video games…there was no shortage of issues for the congress to find.

It is, was, and has never been an issue unique to Japan, of course. Barely legal and teen remain some of the most searched porn terms in the US; TV dramas delight in provocative imagery of supposed high schoolers; and only very recently has men bragging about having sex with 14 or 16 year olds been met with more widespread pushback. As the name implies, it remains a world problem. But there was also no question that Japan was uncomfortably comfortable with sexualizing children, distribution of child porn still legal in the country at the time of the of the world congress.

In the face of international embarrassment, there was no other option: change had to happen, and fast. A bill was successfully drafted between the Liberal Democratic, Social Democratic, and New Party Sakigake political parties in 1998, and would be passed by the National Diet (the Japanese parliament) the next year to little resistance as the Act on Regulation and Punishment of Acts Relating to Child Prostitution and Child Pornography, and the Protection of Children.

The act, finally banning the creation and distribution of pornographic material of minors, defined as anyone under the age of 18, was still vague and lax, specifically banning that which “depicts the image of a Child, in a form recognizable by the sense of sight,” and making special mention to the need to protect artistic freedom, leaving fiction and drawing of minors in an unclear position. Furthermore, the punishments for breaking the law were extremely light, possession of child porn earning not more than a single year imprisonment in the original form of the draft, a fact felt across the world when, in 2017, author of the highly celebrated manga Rurouni Kenshin, Nobuhiro Watsuki, successfully avoided imprisonment and was allowed to resume publication after being arrested for possession of child porn.

This left strip mahjong in a difficult position. Fearing potential legal intervention, JAMMA and other associations began aggressively enforcing their standards while console manufacturers turned increasingly unwelcome towards depictions of nudity, leaving the genre historically filled with high schoolers and lolicon with an increasingly small home. Strip mahjong had become a bomb, and nobody wanted to be the one holding it when it inevitably exploded.

Of course, strip mahjong didn’t die overnight. Very few things in the world do. Instead, like so many of us, it went out slowly.

The same year the act passed, Super Real Mahjong VS, Idol Mahjong Suchi Pai 3, and E Mahjong Sakura Shou released, each the final arcade title of their respective series; the constants and powerhouses of the genre collapsing together and ringing the bell.

Meanwhile, other titles continued to find their way into arcades and onto consoles, such as 2004’s Chuu~ Kana Janshite Hoppai Nyan for the PS2, which received several ports on PC, DS, and PSP, but these were no longer allowed or willing to show nudity, clothes torn just enough that nothing explicit can be seen.

And in 2005, after 21 years of constant releases, the father of strip mahjong Nihon Bussan released the DVD based video mahjong game Ai Suru Cosplay Akihabara. It would be their last title, the company leaving a legacy of 207 adult games as they sunk into the annals of history they’d spent their entire existence desperate to escape. Only a year later, the final non-bootleg strip mahjong game for arcades was released with Taisen Hot Gimmick Mirai eigou, its subtitle translating simply as “Forever”.

It was over.

SEVEN

As arcade strip mahjong gasped its last breaths, dedicated mahjong players began to move elsewhere. Where years ago Super Real Mahjong failed, companies like Konami and Sega now succeed with their Mahjong Fight Club and MJ series respectively; realistic, competitive online multiplayer takes on mahjong, replacing the colorful, personality heavy qualities of strip mahjong with a more serious aesthetic. Onitama dreamed of capturing the joys of connection and individuality possible in mahjong through AI, but in the face of the real, what place is there for characters?

The answer is the one place that has room for everything: the internet. A new wild west of almost no restrictions or constraints, remnants of the vagabond strip mahjong began appearing in browser games and on phones. The series that called the end of the genre’s arcade life, Taisen Hot Gimmick, along with the legendary Super Real Mahjong were both early adopters of mobile phones, releasing several pre-smartphone titles, with doujin developers putting their own works freely onto the net, fueled by nostalgia for what they had grown up with and empowered to lean heavier into the implicit sex of the genre.

And then, behind closed doors at the Fall 2010 Taito Private Show, it happened: a prototype arcade game was revealed utilizing a large vertical display and bold, detailed 3D models in varying stages of undress. Its name? 3D Cosplay Mahjong. Four years later, the obscure prototype would find its way into arcades through Taito’s NESiCAxLive digital distribution system under the name Pai wa Nigasanai, Mentanpin — Doradorara! A loud, aggressively otaku pandering game with stripping that stopped at the underwear, Pai wa Nigasanai remains the first and last arcade strip mahjong game released since 2006, acting as a proud announcement to the world that strip mahjong had never truly died. It had merely changed shape.

Today, strip mahjong continues its quiet existence on the outskirts. Browser-based games like Mahjong Idol Dou Desu Ka?, Bijin OL Tachi to Ecchi na Datsui Mahjong, and Jan Musume Tenpai continue, pushing strip mahjong further and further into the world of explicit porn, where graphic sex is no longer just implied but displayed front and center, while occasional attempts at series revivals find their way onto smartphones, such as Super Real Mahjong P8, the latest numbered entry in the series released in 2019. Applying an idol aesthetic, significantly more story, and a gacha system, the game has been met with disastrous ratings, but highlights the continued desire from both audience and developer for the character heavy stylings of strip mahjong, only further evidenced by the nostalgic resurgence currently occurring on the Nintendo Switch, where Taisen Hot Gimmick, Taisen Idol Mahjong Final Romance, and the Super Real Mahjong series have all seen ports, albeit in censored form. It seems that instead of being forgotten, the world has only begun to remember strip mahjong more and more.

The years where strip mahjong games tower as a shadowed giants — high production, innovative works developed against constraints and in secret by those who would define the history of games themselves, are over. The wider world no longer accepts a genre perpetually seeped in greed and misogyny, objectification and capitalist opportunism; one where you might gamble, cheat, or murder to expose the digital women trapped behind the monitor. But it is also a genre that celebrates sexuality and personality, doggedly joyful and silly experiences that early on understood the connections possible between us and those false people of the game — a genre with influence far beyond its seemingly niche nature, extending even past games themselves. They are, in other words, complex, just like everything in the world is. And it is in that world that we live, changed, knowing or not, by these profane games of tits and tiles, built off the backs of bachelors.

Music of the Week: Vib-Ribbon Original Soundtrack by Laugh & Peace

When people talk about PS1 rhythm game classic Vib-Ribbon, it is 100% of the time in the context of how you can insert your own CDs and play the game with whatever music you’d like. Which rules, we love it for that. But doing so ignores that the music that comes with the game makes for a little slice of J-pop perfection; an ep worth of flawlessly catchy, bouncy, sunshiny numbers that could go toe-to-toe with the best, wriggling and squirming around in constantly surprising ways (very Vib-Ribbon appropriate). Near to top of the game soundtrack pile!

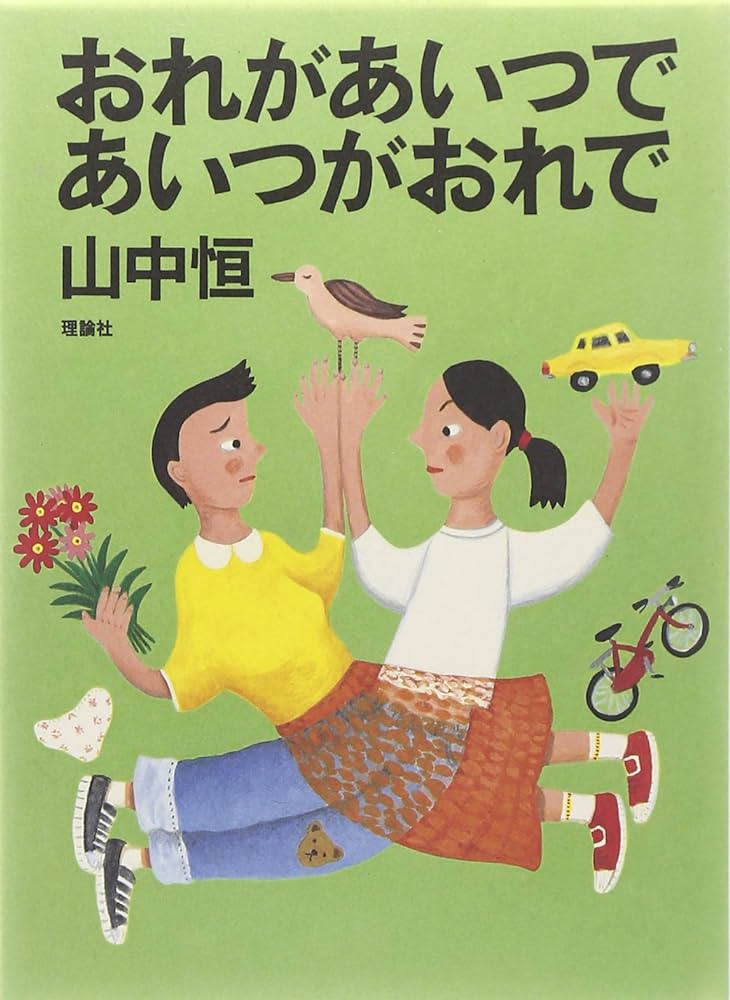

Book of the Week: I Are You, You Am Me by Hisashi Yamanaka

Probably the only body-swap story to ever really matter. Here, the messy matter of sex and gender almost always sheepishly side-stepped in stories like this is attacked head-on, resulting in an aggressive work of dysphoria. Sure there’s plenty of comedy, but being forced to exist in a body that isn’t yours is a nightmare, these young kids being forced to confront sexual assault and abuse and attempted grooming. It’s often genuinely distressing, I think! Some might bristle at its constant assault of traditional gender values and its repetition—how many times can the main character insist that he’s not a girl, but a boy—but without either of those, what would be the point? It wouldn’t be honest. It wouldn’t be real.

Movie of the Week: Evil Dead Trap 2 (dir. Izo Hashimoto, 1992)

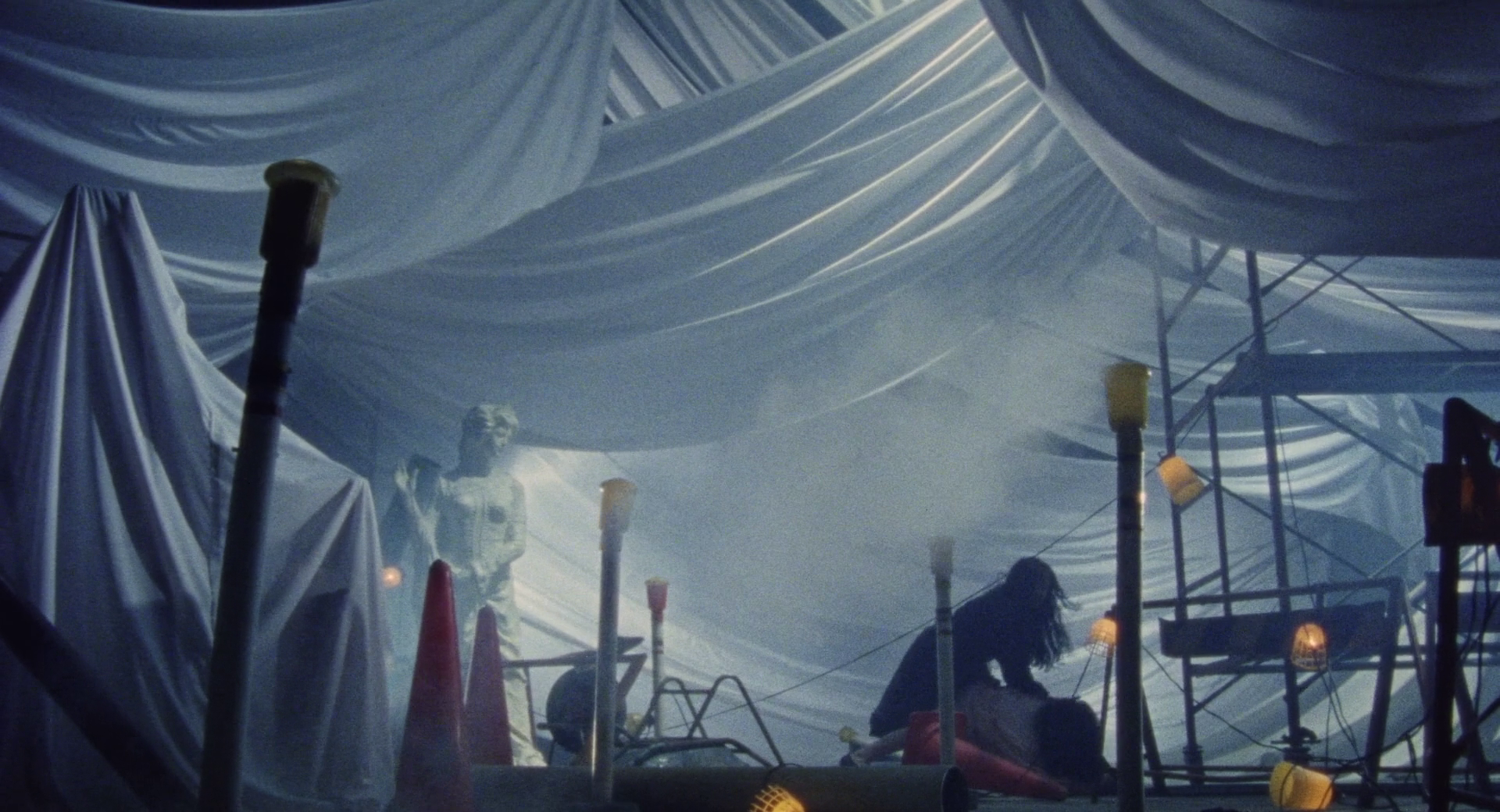

Nobody in the world would have minded if the sequel to grimy horror flick Evil Dead Trap was a hastily thrown together bit of nothing. That’s the natural order of things—it’s what you expect. But Hashimoto is a man who defies nature, and Evil Dead Trap 2 is probably a full-blown masterpiece. One of the greatest looking horror films ever made, this artsy color soaked giallo ode features a script by legendary weirdo Chiaki K Konaka, who packs so many ideas and themes in that the movie becomes this bizarre, artful tapestry of modern life. Yeah, it’s almost always slow and hypnotic, but at the same time it climaxes with a literal abyss gore hole leading to a concrete hell two serial killers battle to the death in. If that ain’t cinema, I don’t know what is.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!