Talking games | Fatal Frame

Cameras, ghost hunts, and a past that hasn’t passed.

Everywhere is haunted. Any building that survives long enough, has enough people pass through its walls, will inevitably welcome ghosts. My old house was haunted, or so we liked to say sometimes—stories about noises in the dead of night or a sink turning on to fill up a pitcher when nobody was around. The land we lived near was haunted too, by Native American’s whose home was stolen for the comfort of our own. And of course so was my school. There was a suicide in the theater department, a spirit living under the stage, the same story as every school. Whether you believe or don’t doesn’t matter: You know as many hauntings as you do places in the world.

It’s the same for the mansion Fatal Frame takes place in. It’s a place as haunted as they come. The ghosts are everywhere in it, hiding in every corner you look and every corner you don’t. They watch, they startle, they play out their already ended lives out on repeat, but most of all they wait to be seen.

Released in 2001 for the PS2 and spawning one of gaming’s most famous horror franchises, Fatal Frame—about a young woman exploring a very cursed Japanese-styled mansion in search of her missing brother—is primarily known for its Camera Obscura that all but consumes every inch of the title. It’s a camera that can capture a reality beyond the one our eyes can see, that can reveal the living past. A machine for seeing ghosts.

It’s easy to make fun of spirit photography as such a quaint and silly thing, especially in the age of photoshop and CG and AI generation—tools that blur the already murky waters of representation versus reality and make older attempts look like grade school pranks—but the spirit of this huckster form thrives even today. It’s just changed shape. Now, instead of old superimposed daguerreotypes or floating orbs in cheap digital, we have video of...well, the exact same things, along with noises from nowhere and surprising shadows and all sorts of technology to measure temperature, radio waves, magnetic forces, micro-sounds, etc. Ghost hunting shows have been a mainstay in popular culture for at least two decades now, moving increasingly digital to YouTube channels and livestreamers dedicated to wandering hotspots and dragging out the spirits that remain, transforming the homes of the dead into Halloween-themed tourist destinations.

(Using this chance to mention that I’ve talked more in detail about Japanese spirit photography in a post about the PS1 game Kowai Shashin, and I’d recommend going over that because Fatal Frame shares more in common with that cult kusoge title than I thought.)

Ghost hunting, by its entertainment-first nature, is all about the present. Oh sure, they make vague gestures towards history and the past and what the walls of the building they are spelunking in have soaked up, but it’s all pretense, table-setting for an endless supply of harmless, spooky dessert. It’s thrills to be munched on and forgotten minutes later. But the truth of ghosts is the truth of life and the truth of time: The present isn’t the present just as the past isn’t the past. It all exists together at once. What are ghosts, after all, but the past refusing to end?

Fatal Frame is a game about that singularity of time. Over the course of its roughly eight hours, the past and the present melt together until any temporal delineation ceases to matter, time collapsing into a constant single moment. What begins as catching glimpses of wandering ghosts quickly becomes staring through peepholes to watch events from years ago play out in other rooms, walking through halls that have returned to an older state, and ultimately physically interacting with past lives as everything overlaps. The past thrives here, spirits representations of history and tragedy—those things that never really die but repeat time and time again.

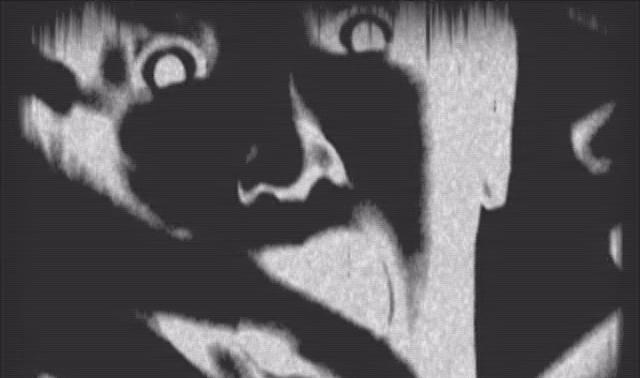

And it depicts this non-linear understanding of time, this time defined by ghosts, with remarkable style, freely shifting from its more traditionally horror hues to scratched up old film, or aggressively harsh black and white with contrast so heavy it massacres any in-between tone. Just as you (often unknowingly) mingle in and out of years, the textures of the game are constantly shifting. Along with these plunges into dying film, cutscenes are naturally smoother, softer than normal gameplay, where colors will make frequent surprises, jumping from rust and wood one angle to the heavily saturated blues of moonlight through windows the next. It’s a total swirl, quietly connecting Fatal Frame’s rumination of history with place in a very physical way, suggesting that the nature ghosts and the nature of architecture aren’t all that different from each other. Both continue and change and remain the same all at the same time for generations; both are dumping grounds for our identities as the living to an extent that we are incapable of fully understanding them.

And then you turn on your camera.

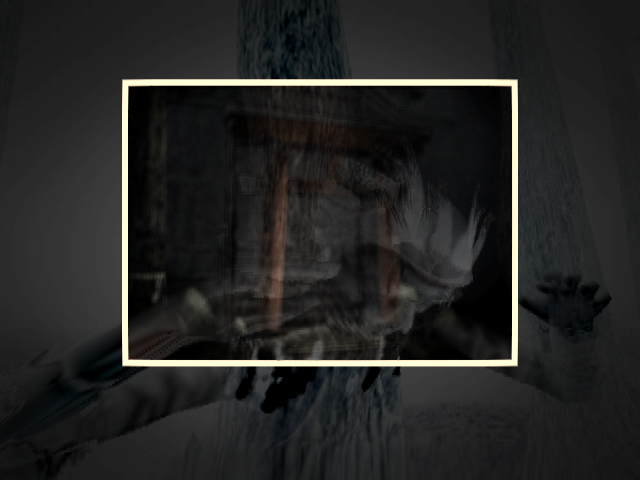

Looking through the Camera Obscure doesn’t just let you see ghosts, and it certainly doesn’t just give you the chance to fight back—though it does, with an arcade influenced style that encourages playing with death and getting close to these vengeful spirits as possible. No, the most startling and affecting use of this legendary camera is also its most simple: Looking through the Camera Obscura quite literally changes your view of the world. It rips the game’s carefully designed and classically survival horror fixed-camera angles away to go first person, giving the player direct control and a total recontextualization of place while also once more shifting its textures to something highly sharpened, granting a grungy, rusted tactility that isn’t present otherwise.

It’s all sumptuously directed stuff, carefully considered down to its moment to moment gameplay, working with a delight in variance and bubbling energy most reminding me of Yoshimitsu Morita’s virtuosic horror satire The Black House. Here, even battles against the dead become just as much a fight of aesthetics as one of survival, all camera flashes, lights popping, and ghosts posing all wretched. Most arrestingly, every shot taken with the Camera Obscura climaxes with a gorgeous, soft yellow frame around the center of the screen, the world outside the limits of the camera’s frame still visible but faded out and dimmed. Every shot becomes some sort of horror-tinged pop art, an unspoken recognition of the entertainment we derive from the tragedy of our dead and develop through our technology.

Which I mean, that’s all Fatal Frame is at the end of the day. Technology. Entertainment. It’s a complex game developed for fun and for profit. It doesn’t even end there, Fatal Frame being a perfect example of a game that grows deeper in the age of emulation. Cameras can capture ghosts, video can capture the camera, and now all of it can be captured together, emulators giving the player the ability to freely take screenshots of the game whenever they want. Where does the spirit photography stop and end in cases like this?

Fatal Frame might have ideas about the perpetual present that is the past, but in the end, it’s hardly any different from ghost hunters invading a hotel with video cameras. It’s all but impossible for us to interact with spirits in any other way anymore. The ghosts here wait to be seen—by the camera, by the characters, by the player—trapped forever in a game and existing in a perpetual state of anticipation and acknowledgment for our pleasure. In that sense, it’s no wonder why we invent and hunt ghosts so often, why we try so hard to make them real and believe. They’re the most human thing there is.

Music of the Week: >(decrescendo) by The Gerogerigegege

Deeply unsure if there is a single musical artist more important to me than Juntaro Yamanouchi, the face behind legendary dada-punk performance art project, The Gerogerigegege. When I tell you basically every single art endeavor I tried in high school was influenced by the 'ge in some way, I mean it (down to my own noise project where I snuck burned CDs with hearts drawn on them into stragner's lockers). Anyway, after two decades of silence, Juntaro came back better than ever, and >(decrescendo) has become one of my favorites of their projects--a deeply emotional 40 minutes of field recording ambient both meditative and overwhelming. It's the kind of record that never really ends, even after the music has stopped.

Book of the Week: Another by Yukito Ayatsuji

In the English world, Another is mostly remembered as that one supremely edgy gore-filled horror show with the eyepatch girl, but the original novel is an arresting, atmosphere-soaked supernatural mystery from one of Japan's greatest and most influential in the field. There aren't many in the world better at writing densely gothic unease than Ayatsuji, and he really goes all in here, patiently dragging the reader into its madness, leaving you (or at least me) mired in this purgatory of uncertainty, desperate for rational answers. Obscenely readable!

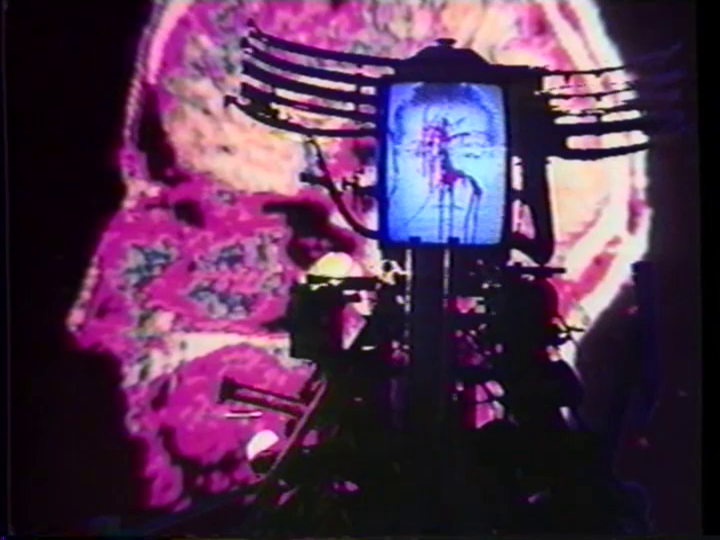

Movie of the Week: Skin #5 Video Mix M.M.M. (dir. Norimizu Ameya, 1989)

Will probably write about more in-depth one day, but this rare surviving recording of a Tokyo Grand Guignol play (lightly adapted for film) is as me-core as it gets. It's a VHS that feels like it was dropped out a hole to hell in the middle of a concrete labyrinth, an absurdist ero-guro cyberpunk descent into techno-paranoia philosophizing backed by hip hop dance numbers, VR quiz games, and insane body horror makeup. Maybe the coolest thing ever made by maybe the coolest people who have ever lived.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and the Japanese Film Festival has started streaming Japanese films for free!