Talking games | Kamaitachi no Yoru

Losing my mind searching for answers in 1994's influential obsession simulator.

We are back! Welcome to the new home to my dumb posts. If I didn't bork things and you are reading this as an email, then thank god, it worked! And if you didn't get it and it isn't in your spam or promotion folders or anything, then I guess I'll never know because you definitely aren't reading this.

Anyway, before we get started proper: I know I took a nice long break, but that doesn't mean I haven't been doing anything. First, if you missed it on my post announcing the move, I was blessed enough to be in the great Shy's buddy list post where I looked back on my year with art. Definitely check that out and follow Shy because she is a genius.

Also, I had a second (!) article published on PC Gamer! Yet again I'm digging into a new Vampire Survivors styled game, Time Survivors, where I talk about the comedy inherent to the genre. Give it a read!

There's a even handful of other projects I've been toiling away on top of that stuff at that won't see the light for a while which are all super cool and exciting. 2024 is the year of Baxy, baby!!

On to the art!

What is a kamaitachi?

The name makes it seem obvious enough; kama means sickle and itachi means weasel, so put them together and you get a sickle weasel. And certainty, that’s what they are, a sickle wielding weasel yokai (Japanese spirit) coming from the central region of Japan, these invisible creatures come in on cold windstorms and slice human flesh, wounds noticeable but painless.

But that doesn’t really answer the question. It gives us a shape and image, but that doesn't get us any closer to truly understanding the creature, just as seeing someone's face doesn't let us know who they really are. They remain obscure, existing only as fiction in our minds, formed different and unique to each person who thinks about them.

Sure, we can dig further and postulate on the why, on the origins of this folkloric creature, on the historical socio-economics and geo-politics of ancient Japan that allowed the belief systems to create the kamaitachi to come into existence, but at the end of the day, that’s all it is: postulations. Theories. Guesses. The truth, like all truths, is a mystery. And mysteries never have answers as simple as you’d expect.

Released in 1994 for the Super Famicom, Kamaitachi no Yoru was developer Chunsoft’s follow-up to the genre defining, hyper-influential haunted house experience, Otogirisou. That title, recognized as the first sound novel, stripped the adventure genre back to its muscle and bone, menu navigation and dialogue inputs replaced with the striking simplicity of nothing but words and sounds and pictures—a sort of digital choose your own adventure book. And for their follow-up, their iteration and perfection of this new genre, it would have been terribly easy to make Otogirisou 2. But they didn’t. Instead, they made what seems to be a traditional mystery.

Set in that most classic of classic murder locations—a snowed-in lodge cut off from the outside world—Kamatachi no Yoru certainly begins traditionally at least, lodgers dropping dead one by one in locked rooms in a way not dissimilar to Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None. Suspicions rise, red herrings fly, and everyone has a motive. It’s all exactly what you’d expect; a classic, structurally conservative, by-the-books whodunnit.

There’s just one problem: Kamaitachi no Yoru is a game. And it knows it.

Written by established author Takemaru Abiko, Kamaitachi no Yoru exists firmly in the world of the shin-honkaku (new traditionalist) movement of Japanese mystery fiction. Beginning in 1987 with the publication of Yukito Ayatsuji’s The Decagon House Murders, shin-honkaku represented a push back towards the golden age of the genre, when fair play reigned supreme. It is a movement in love with mysteries not as a tool for social critique, but as a vehicle for puzzles, for complex webs that the reader can theoretically solve. And while mysteries have always been at the forefront of meta-play in fiction, purposefully twisting expectation and accepted soft-rules of literature, the shin-honkaku movement pushed it all even further, becoming a wild playground for post-modern exploration. Characters are suddenly named after real mystery authors, engage in debates on theory and practice of the genre, and find themselves wandering outside the very confines of their story.

This all certainly applies to Kamaitachi no Yoru. Here, the genre’s innate fascination with the architecture of form finds a new home in video games—this art defined by systems and control—and does what shin-honkaku does best: exposing the bones and poking at the muscle of its medium.

Take my first playthrough of the game, which could hardly be called a mystery at all. Sure, there was a body and sure, there were suspects and theories, but without any solid clues, I stumbled blindly as the number of corpses rapidly increased and potential answers even more rapidly vanished, everything getting all mixed up in my head. Who could have committed the crime? Was it Makimoto, the mountain man who arrived late? But no, he was with me when everyone died. Was it one of the three young office ladies who locked themselves up in their room upstairs? But that doesn’t make sense, they have alibis for nearly every death. Was it the owner of the lodge, Kobayashi, or his wife, or the rich Mr. Kayama, or one of the part-timers working there? Was it my girlfriend? Was it me? By the end, wrapped up in doubt and uncertainties, I started to believe. Maybe it really isn’t possible. Maybe there isn’t a logical answer. Maybe it was the kamaitachi.

The whole experience carried a palpable, propulsive fear, a mounting paranoia and hopelessness as logic gave way to madness; a sensation only heightened by the bold aesthetic choice to render every character as static, semi-transparent silhouettes. Stripped of detail, the player is sucked into a world of shadows, a place where reality has been removed, only the afterimage remaining. It feels, in other words, false; artificial.

Kamaitachi no Yoru is a game quietly obsessed with artifice. It pushes up against its confines at every turn. Time and time again, characters remark that the events are like a dream or a nightmare, or that it’s all reminiscent of some awful story. They compare their situation to a play and reference pop culture. “It’s like we are in a Jason movie,” they say. “I saw this sort of thing on TV once,” “I heard about that on the news.” They have this unspoken need to mold their life into the shape of fiction, to view the world through the lens of media. They can’t help it; it’s the only way for them to not go crazy. We can’t help it either, drowning ourselves in entertainment in a futile effort to understand and compartmentalize. I play the game so that I can forget; I play the game so that I can understand.

My second playthrough was different. Armed with knowledge only possible through death, the story repeated, but this time the protagonist, once timid and panicked, was now bold and proactive thanks to me making new choices. This time, though I wasn’t sure, I had ideas. I had theories. This time, I announced the name of the killer.

There are only three times when Kamaitachi no Yoru breaks from its form of text and multiple choice. The first is when you name the main character, the second, when you name your love interest. The third is when you declare the identity of the killer. In a wildly disorienting moment played as matter of fact as anything ever has, the game discards its pretensions, looks at you, the player, and demands you a choice. It is the video game equivalent of Ellery Queen’s challenges to the reader, where the narrative briefly breaks to goad the reader into guessing the answer. The only difference is that as a game, by making a choice you are forced into the narrative, changing its course and implicating yourself in whatever happens.

Luckily for me I chose right. The game ends, the credits roll. The mystery has been solved and answers reached. The game begins again.

Some people say this is where Kamaitachi no Yoru really starts, that the mystery of the game lies past its own solution. After the murders are solved, things start changing more drastically. What once were options are now decided for you and what weren’t are. And as you play, exploring these new possibilities, the story begins to branch in wildly different ways, game suddenly reconfigured into different genres as it asks a single question: what exactly is the kamaitachi in the title?

There is a scenario where the kamaitachi is a vengeful ghost from the past; there’s another where it’s a super spy hiding amongst the lodgers. Dig deeper and find the kamaitachi as a metaphor for love, game becoming a suggestive romantic comedy. Deeper, deeper, and find a dungeon that shouldn’t be there; treasure; a code hidden within the game’s text; a message left from the creators. The shape of the kamaitachi shifts like the wind, the real mystery of the game only becoming more obscure the further down you go. What answer lies at the end of Kamaitachi no Yoru? Is there even a bottom?

In one scenario, the protagonist (who I gave my own name, Baxter) spots a Super Famicom shortly after arriving at the lodge. Sitting next to it are two games: Otogirisou and Kamaitachi no Yoru. He puts the second one in and begins to play. It’s just like everything that just happened. In the game in the game, the protagonist (who Baxter named Baxter) spots a Super Famicom shortly after arriving at the lodge. Sitting next to it are two games: Otogirisou and Kamaitachi no Yoru. He puts the second one in and begins to play. How does it know everyone’s name? How does it know what they did, what they are thinking? A third Baxter puts Kamaitachi no Yoru in the Super Famicom and begins to play. Nobody knows where they are anymore. Are they part of the game or simply playing it; are they thinking their own thoughts or reading thoughts decided for them? Who are they? Who am I? They (I?) see a Super Famicom and begin to play Kamaitachi no Yoru.

We come to mysteries for answers. Despite the name, their joy is in solving them, in knowledge, in dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s and killing questions. They are the great escapist fantasy in that way; comforting assurances that answers exist and truth is absolute, that questions can be solved. But deep down we all know that as much as we strive, our knowledge will forever be incomplete, our world forever one made up of fictions we can believe in to hold it all together. Answers, real answers, are as elusive as a kamaitachi. How nice it would be to be in a game.

At the end of the spy themed scenario, it is revealed that the kamaitachi—that super spy everyone was hunting for—never existed in the first place. It was a lie from the very beginning; a trick that got out of hand. In the gaming scenario, one of the Baxter’s gets fed up and shuts the game off, their TV screen filling up with white noise. As if predestined, the rest follow suit. One by one the screens turn off; a mirror in a mirror of static. And just before he turns the final one off, the Baxter in the game sees something in the reflection of his television.

He sees me.

My TV fills with static. Outside, I can hear the wind.

What is a kamaitachi?

Music of the Week: Osorezan/Doh No Kembai by Geinoh Yamashirogumi

Look, we're all guilty of it, but the entire world deciding Geinoh Yamashirogumi is "that group that did the Akira soundtrack and nothing else" is a sin of the highest order. Here, in two monolithic tracks, the group showcases exactly what makes them so vital in a wild blend of gamelan, Gregorian chants, prog-rock and psychedelia. It's dark and moody for a time, like you've been trapped in some ancient temple on a full moon night, witnessing something extraordinary and out of time, but it doesn't take long to grow into a chorus of cursed howls and screams and wails. All this while also low-key grooving heavy. It's hypnotic stuff, as thrilling as it is chilling; the kind of music that kicks my imagination into overdrive.

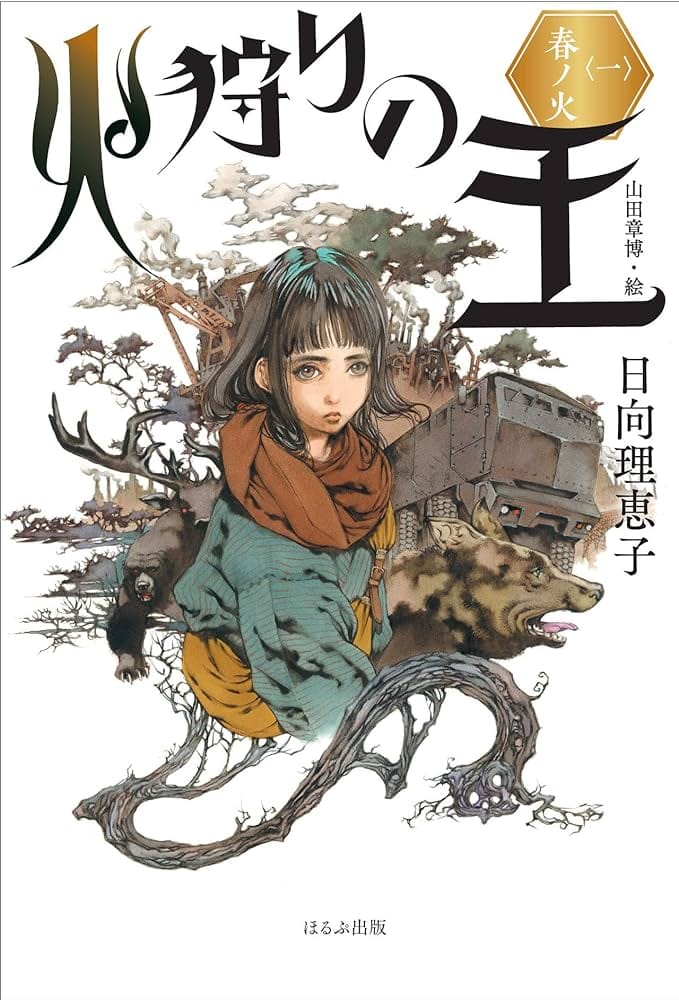

Book of the Week: The Fire Hunter by Rieko Hinata

Currently being expertly adapted into an anime series, this is future-flung fantasy of a world where any proximity to fire causes people to spontaneously combust is dark and singular, all shadows and dirt and oil and rust. World building details so interesting they could make their own books, such as the older generation being blinded as children and spending most their lives working in mines, are turned into casual asides as the story barrels bigger and more out there at every turn. Packed with bugnuts concepts and imagery you'd expect from like, a 70s French sci-fi comic told with surprising patience and a devotion to atmosphere. That the books feature illustrations from legend Akihiro Yamada, most known for his work providing art for The Twelve Kingdoms series, certainly doesn't hurt things!

Movie of the Week: The Beast to Die (dir. Toru Murakawa, 1980)

Imagine a movie that starts where Taxi Driver ends. The Beast to Die is a relentlessly bleak and frigid thriller filled to the brim with silence and long takes and classical music as it follows a man who has become a hollowed, haunted, vile physical embodiment of the nihilistic chaos of the world. Yusaku Matsuda owns the role, acting as if he is nothing but skin stretched into the shape of a person until the climax when he erupts in a manic explosion, war trauma manifesting in increasingly disorienting filmmaking. A great time if you want to feel bad!

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and here's a very underseen mini-doc about one of 2023's best underplayed games, Humanity