Talking games | Linda Cube

An anti-RPG classic and the story we all tell.

warning: full spoilers for Linda³, a game with no English translation 😭

It is a commonly held belief that there are only a small number stories in the world which all others fall under. Journalist Christopher Brooker popularized the idea of there being seven: overcoming the monster, rags to riches, the quest, voyage and return, comedy, tragedy, and rebirth. Poet Jorge Luis Borges saw only four: the story of a city defended, of a return, a search, and the sacrifice of a god. For his part, writer John Gardner had his words taken from him, misinterpreted to shrink the number even further down to two: a person goes on a journey, and a stranger comes to town.

The number might change, but the sentiment remains the same: our lives are consumed by retellings, by fiction repeating the same themes and the same structures, tweaked and twisted to reflect in different ways and convince us they are new.

In Linda³, there are three stories, and they end in silence. After a journey lasting years, the first of these finds nearly all of Neo-Kenya abandoned in the face of the rapidly approaching Grim Reaper — an asteroid on a collision course with the planet, set to wipe out all life. The hotels are empty, the weapon shops unstaffed, characters loved and characters hated long since escaped to the stars. Only the protagonists, a boy named Ken and a girl named Linda, are left. Visiting Ken’s once bustling hometown, now empty and lonely, you can visit the prison scientist Panhaim, who you fought years ago, is locked up in. He can be visited several times throughout the game, where he laughs like he always does, making uncomfortable innuendos and slipping inappropriate items to Ken. But this time is different. This time, his cell door is unlocked. You can walk inside. You can see his corpse. On the cell wall above him are two words, written roughly in blood.

Love Forever.

There’s no denying it — Linda³ (pronounced Linda Cube) is a strange game. Originally released for the PC Engine in 1995, and purposefully designed as an antithesis to director Shoji Masuda’s previous blockbuster project, Tengai Makyou 2 (at the time the most expensive video game production ever), it is a game born from creative frustration intent on dismantling genre conventions and traditional gaming power fantasies; a structurally unique experience that is at turns purposefully frustrating, thematically cruel, and joyously contradictory.

Beginning with an idea seeded years prior in the mind of a cinephile Masuda who was falling deep down the rabbit hole of adult videos and becoming increasingly fixated on understanding the normalization of physical and sexual violence in them, Linda³ eschews a single overarching narrative to instead present three separate scenarios, each telling its own divergent story within a broad framework: Neo-Kenya, Ken and Linda, the unstoppable approach of the Grim Reaper, and an ark. Said ark, which resembles Noah’s, suddenly appears from the sky before the game begins, bringing with it an appropriately biblical command to fill the ship one male and one female of every animal. Ken and Linda volunteer to be the humans, and the stories begin.

Despite the temptations of this premise, Linda³ does not allow for any grand heroics. There really is no stopping the asteroid — no matter what you do, it will fall, and it will destroy everything. There are no legendary heroes or mythical chosen ones; no god to defeat or fate to deny. Ken, and by extension the player, is powerless, little more than a cog in a machine who, instead of anything as lofty as the world, is only able to save, as Masuda describes it, “100 disgusting animals and a single bad-mouthed girl.”

Scenario A, Happy X-Mas, opens the way they way they all do: warm, optimistic, and full of humor. Ken’s mom offers advice, his co-workers playfully take jabs at him, and Linda — headstrong, energetic, and confident — playfully mocks you for being at level one. From the jump, the game revels in its silly, absurdist parody, presenting as a happy, loving ribbing of a beloved genre.

This does not last. Before long, everyone in Linda’s village vanishes except for her, her memories stripped away, leaving the once brash, playful woman you knew meek and docile. Eventually the culprit emerges — Ken’s secret identical twin Nec, who has taken control of Linda, forcing Ken to watch a perfect mirror of himself steal her autonomy and control her as if she were a doll. It’s here, in a long chase to free Linda and return her memories, that you meet the scientist Panhaim, willing to do anything to keep the woman he loves, Elizabeth Green, young and alive, the way he wants and remembers her.

It’s also here that Linda³ reveals its idiosyncratic take on traditional RPG gameplay. Setting the player free in an open world (each scenario offering different areas to explore), combat plays like a complex distortion of Dragon Quest, where battles are fought not through a single screen, but in four directions, enemies able to surround and flank the player, blocking escape routes or increasing their critical hit rate. Terrain complicates things further as mountains, forest, water and sand of the overworld are reflected in the four quadrants the enemy can occupy, giving appropriate stat boots to certain animals.

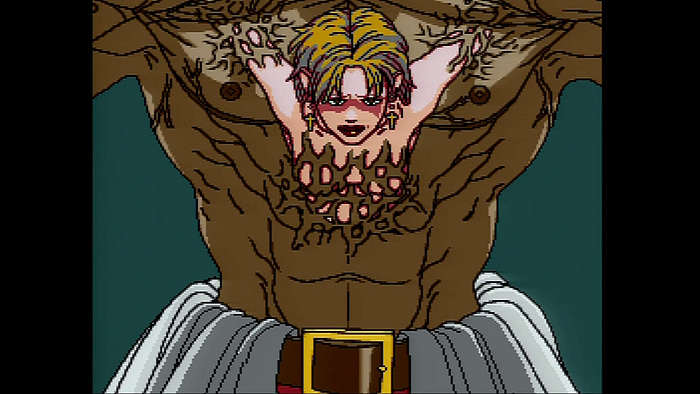

The regular tools of the genre are still present, with options to attack and defend and use abilities, but you can also transform into grotesque mutations of some animals, the disfigurement and horror of the human body — of being trapped in a corpse you might not have control over — turned into a central mechanic, offering various stat buffs and debuffs to the player that are of vital importance when facing both the dangerous and the defenseless.

This is because the goal of the game is, in opposition to what so many RPGs have taught, to capture, not kill. Killing an animal in Linda³ accomplishes nothing; no experience earned or items given. Instead, the player must lower the enemy’s HP to as close to 0 as possible — sometimes a little over, sometimes a little under — to capture the animal, handicaps such as debuffs or weaker equipment becoming increasingly necessary considerations as the game goes on.

The result are fights that become strategic plays defined not by the battles themselves, but by positioning and the hunt, preparing appropriately strengthened weapons and choosing to chase an animal or waiting to strike until they are in an advantageous area.

And there is a lot of hunting. While some animals can be easily found roaming the overworld, others hide deep in complex, purposefully frustrating systems of caves, or only appear during certain seasons, or when you set up camp in specific locations. As a result, NPCs in Linda³ become valuable resources of information, hiding rumors and legends of obscure animals among flavor dialogue and world building.

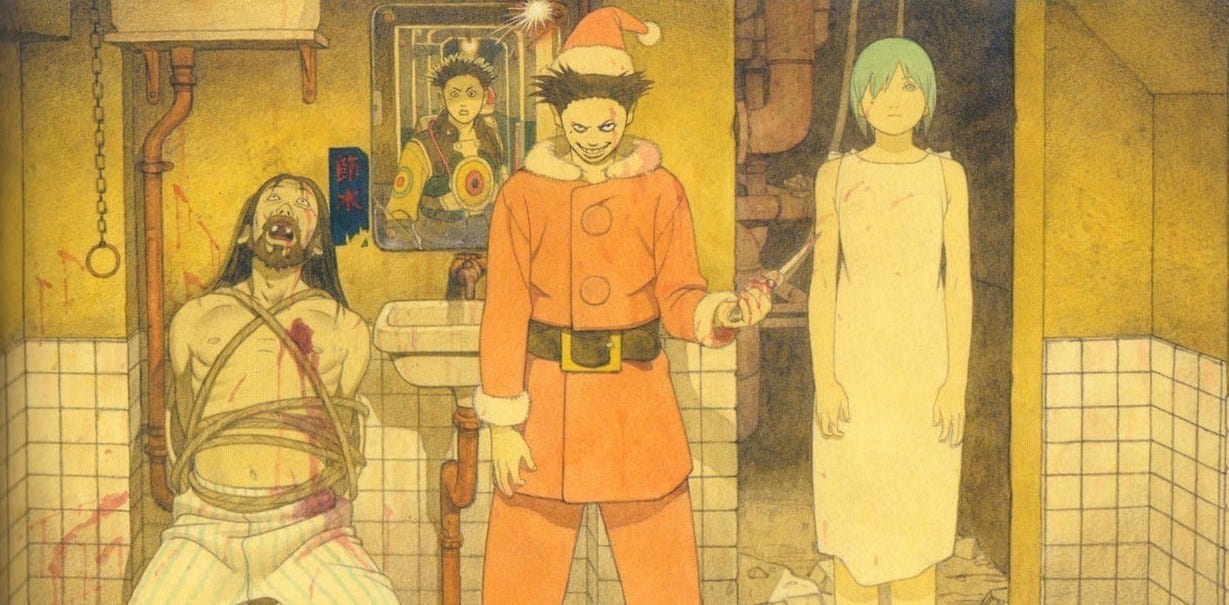

As Scenario A nears its conclusion, Linda freed from Nec’s control, one final villain emerges: Linda’s father, who has forcibly fused her mother into his chest, forever turning the two into one physical being. He can’t bear the doubt anymore; every time he looks at Linda, his beautiful daughter, he is forced to recognize that she isn’t his. Her features are too different, her skin too white. He tells her he loves her. He kills himself.

The story ends. There is nobody left. Families torn apart and loved ones gone, Ken and Linda board the ark. Credits roll.

Scenario B, Happy Child, resets the world to its once vibrant, playful state, but it rings hollow now — empty echoes in wake of the truth. Still, for a moment, for just long enough to make you hope, things seem different. Nec is nowhere to be seen. Linda’s village remains untouched, and her parents are together and happy.

And then suddenly, an ant-like soldier appears and slaughters them all, murdering Linda’s parents and blowing off her arm, which is replaced against her will with the arm of her father. She runs away, unable to escape the grief that has become her body.

Slowly, Scenario B unfolds into the story of Sachiko, a character who replaces Linda in your party and a robot made in the image of a dead girl, created to act as a daughter for a grieving, obsessed scientist named Emori — the same scientist who gave Linda her father’s arm. Again the relationship of father and daughter is explored, and again it ends in tragedy. The scientist sees Sachiko as a tool, an object of violence and sex. He goes mad and mutates into something horrible, something no longer human. Before setting off on the ark, he attacks in pathetic desperation for closure, but is stopped by Sachiko, who dies together with a man who, through no choice of her own, defined so much of her life. Their burnt corpses before you, the player once again leaves Neo-Kenya, this absurd and broken planet, to its inevitable end.

Masuda never found a satisfying answer to that issue of porn and violence, but it didn’t matter, because after months pouring over books on the psychology, sociology and neurology of rape, books almost entirely written by men with premises and explanations he couldn’t buy, an idea had planted itself deep in his brain. Power.

Linda³ is a game of trauma and violence; of sex and death and control. It is a game of power. Just as the player uses violence and power to break down and capture animals (there is no fanfare or congratulatory message when capturing an animal; only the simple knowledge that they have “stopped resisting”), so too do we see characters, time and time again, stripped of their autonomy. Like the player’s body, twisted into new shapes to enforce their dominance over the animal kingdom, Linda’s body is changed, becoming in turn a mental, emotional, and physical prison. Her memory is wiped, turned into the plaything of a man, and her arm replaced without her consent, becoming an inescapable reminder of past trauma.

And it isn’t only her. Linda’s mother is absorbed into her husband to placate his memories of the past, her body no longer allowed freedom, forced to be a part of vile acts she doesn’t desire. Sachiko is designed to lack freewill, infantilized by her perverted “father” and forced to play out a role that gives him has emotional, physical, and sexual control. Elizabeth Green is kept alive as an object of sexual desire long after she should have crumbled to wrinkles and dust by Panhaim, whose blood will one day stain concrete walls.

Time and time again, men in power oppress and control. Time and time again, things collapse. Tragedy and trauma repeat like the inevitable conclusion of life. Parents die, loved ones are betrayed, free will is held ransom.

Masuda, staring at the shelf of a video store filled with assault.

When Scenario C, Astro Ark, begins, the optimism of the beginning has become unbearable. These characters will die, hurt and kill each other, control and abuse and fight for power over the lives of others in a world already about to end. And you play, and you wait for the pin to drop, for everything to collapse yet again into the absurd and painful truth.

But it never does. In this last permutation, Nec is kind and Sachiko is free. Linda’s parents remain loving and together. Nobody dies, nobody’s body is stripped from them, nobody suffers. Nec and Sachiko fall in love and get married, and the last years of the world pass in peace, the story drifting away into light vignettes of shared love as the game fully opens its world, challenging the player to collect a staggering 100 animals, mechanically re-contextualizing the previous two scenarios into warm-ups familiarizing the player with the world and animals before being fully set loose here. Along the way, you meet Panhaim, living with Elizabeth, who is old now, but is herself and is happy. Emori appears and supports Sachiko, encouraging her to live how she wants. Seasons change and years pass, and eventually a life of adventure comes to an end exactly as it has every time.

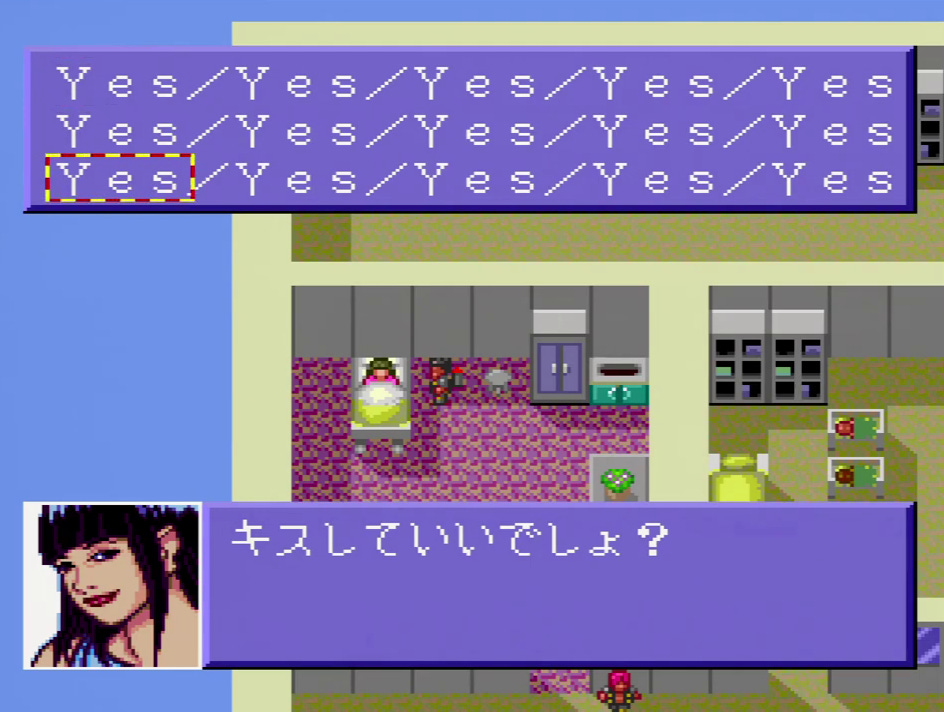

Neo-Kenya abandoned, Ken and Linda board the ark and watch the world end. They embrace. They kiss. For three long, uninterrupted minutes, the player becomes voyeur to something intimate and almost embarrassing, bodies wrapped up together, never to be separated again. The world is gone; there is no more control. All that remains is love.

Linda³ was remade only two years later for the PlayStation and Saturn with updated graphics and music, anime cutscenes, various quality of life improvements, and a handful of extras. The designs of the characters are almost all changed, some minor, some radical. The once pink-haired Linda is unrecognizable, now sporting green. The animals have mutated in different ways. Panhaim lies dead in his cell. It’s all different, but also so familiar variations on the same story. Everything is.

They say there are seven stories, or four or three or even two, but sometimes I think there is only one.

Blood on the walls.

Love forever.

Music of the Week: Happy End - Kazemachi Roman

Talking about something supremely famous for once, but sue me—you can’t talk about modern Japanese music without talking about Happy End, and you shouldn’t because they are the best. A folk rock band composed of four impossibly influential figures (you could write 20 books on Haruomi Hosono alone and still not cover all the ways he has shaped modern music in Japan) which took influence from groups like Buffalo Springfield while also boldly attempting to create uniquely Japanese rock, their debut the first truly Japanese language rock album ever released. But this, their second album, is my personal favorite. “Kaze wo Atsumete” is maybe a top five of all timer track for me and the rest of the album? Just as good.

Book of the Week: The Decagon House Murders by Yukito Ayatsuji

Speaking of famous, The Decagon House Murders is a totemic work of Japanese mystery fiction. Ushering in the age of the shin-honkaku—or new traditionalist—movement, where the genre is brought screaming back to its golden age of puzzle box murders and solvable crimes, this book is a genre manifesto disguised as fiction. With a cast of characters all using the names of classic mystery authors engaging in long debates about the ideologies of mystery fiction, Ayatsuji writes with ice cold prose, crafting something deeply intelligent whose influence is still felt heavy today. The reveal remains one of my favorite moments I’ve ever had reading—full body goosebumps.

Movie of the Week: When Twilight Draws Near

Written by controversial auteur Nagisa Oshima and directed by Akio Jissoji (who I will be talking more about later, trust), When Twilight Draws Near is a taut, masterclass excercise in tension. Set entirely in a small apartment where four university students turn on the gas and place bets on who can stay in the room the longest, not a second is wasted in its lightning forty minute runtime as a dense, angry, politically charged assault of nihilism and ennui threaten to drown the viewer. It’s all waiting and staring and talking here, and every second is almost completely unbearable.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!