Talking movies | Gothicmade

nobody's ever gothicmade an anime quite like this

Nothing seems obscure anymore. In the modern internet age, it feels harder than ever for something to disappear, to vanish, to not be there waiting on some website, reputable or otherwise, for any curious eyes to see. Today, the idea of lost media has become its own content creation industry, shifting the term from previous implications of silent films destroyed by the thousands amidst the violence of war to internal test pilots and comics not available digitally. And sometimes I find this change in definition annoying, and in its most hyperbolic moments insulting to both history and the art, but I also can’t really blame people for thinking about lost media in such a way. That’s just the shape of things now. So little is blessed with the allowance to be lost.

Written and directed by Mamoru Nagano, it’s all but impossible to consider the infamous 2012 anime film, Gothicmade: The Songstress of Flowers (Hana no Utame Gothicmade), separated from its stubborn inaccessibility. Never released outside of Japanese theaters, to view its short seventy minutes requires both luck and effort, the rare screenings exclusively put on through fan campaigning for unadvertised one night events. As such, Gothicmade remains a rarity in modern narrative filmmaking — a work only viewable through concerted, active purpose; a film Wikipedia calls “partially lost”.

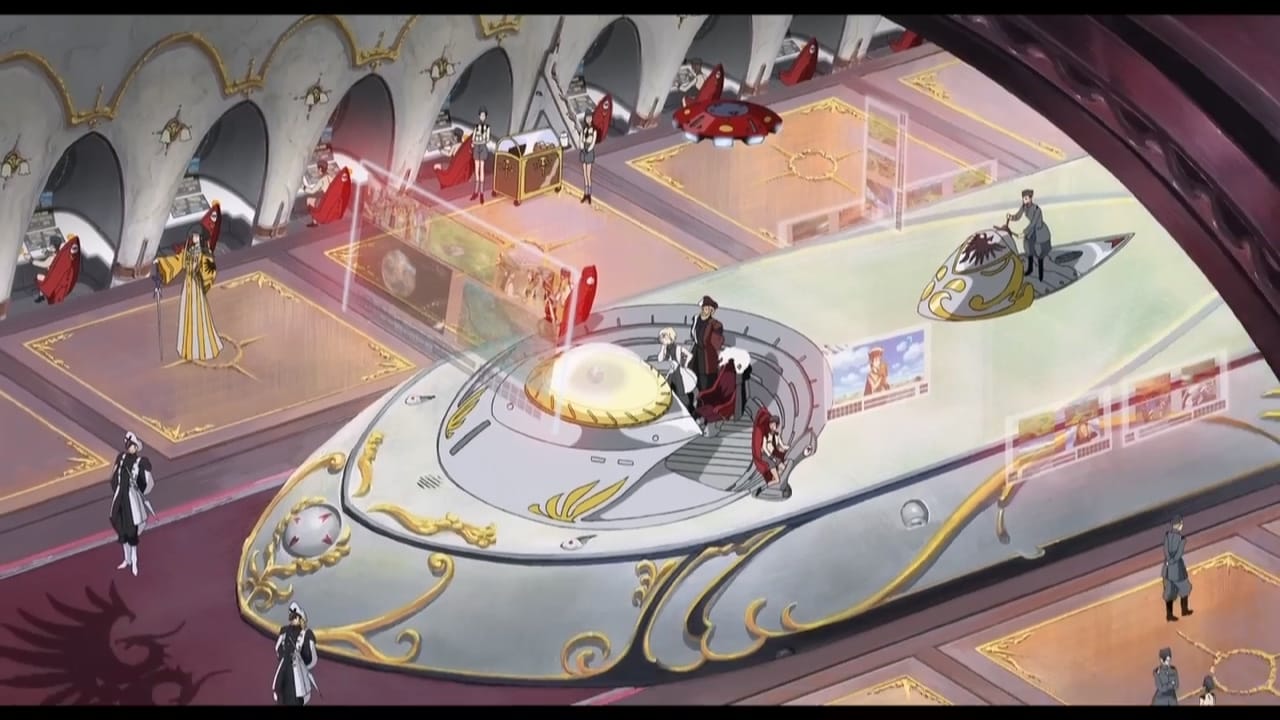

Following the pacifist Bellin Ajelli as she travels to her planet’s capital and her evolving relationship with the prince Truhallon, acting as her bodyguard in the face of a suspected terrorist plot, Gothicmade is decidedly not the type of movie you might be expecting. Sure, the poster seems to promise dark giant robot action and yeah, the title brings to mind images of goth girls in maid outfits (or maybe my brain is just poisoned), but the reality is something slower and quieter than any of that. This is story that exists almost entirely in pastoral imagery, gentle folk music, and contemplative fades to black, each scene clearly delineated like the chapter in a book. It’s a movie about two people, stand-ins for broader moral positions, talking and lounging and sometimes sitting together in silence and slowly understanding the other — a fable from the future, filtered through sci-fi politics.

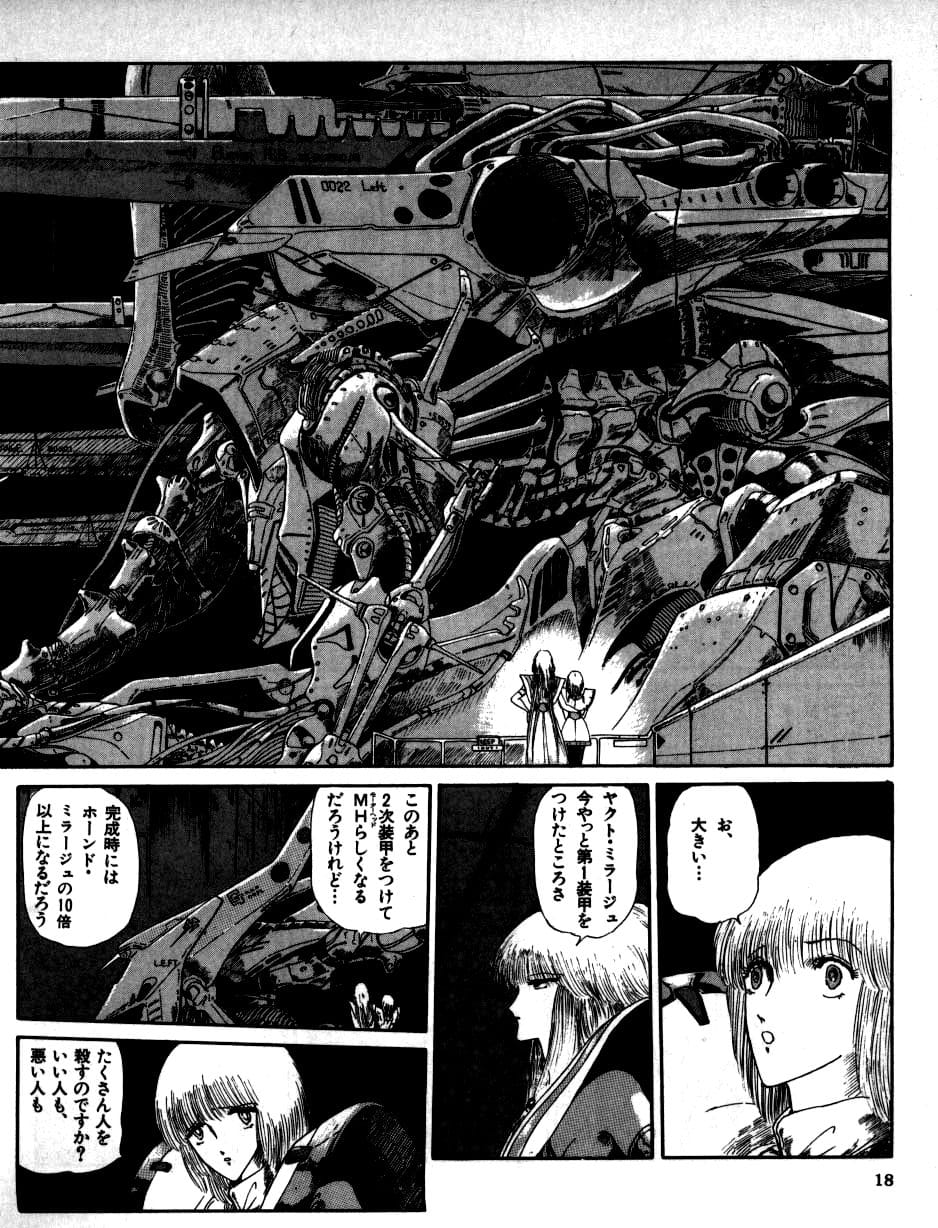

Not that there aren’t any giant robots.

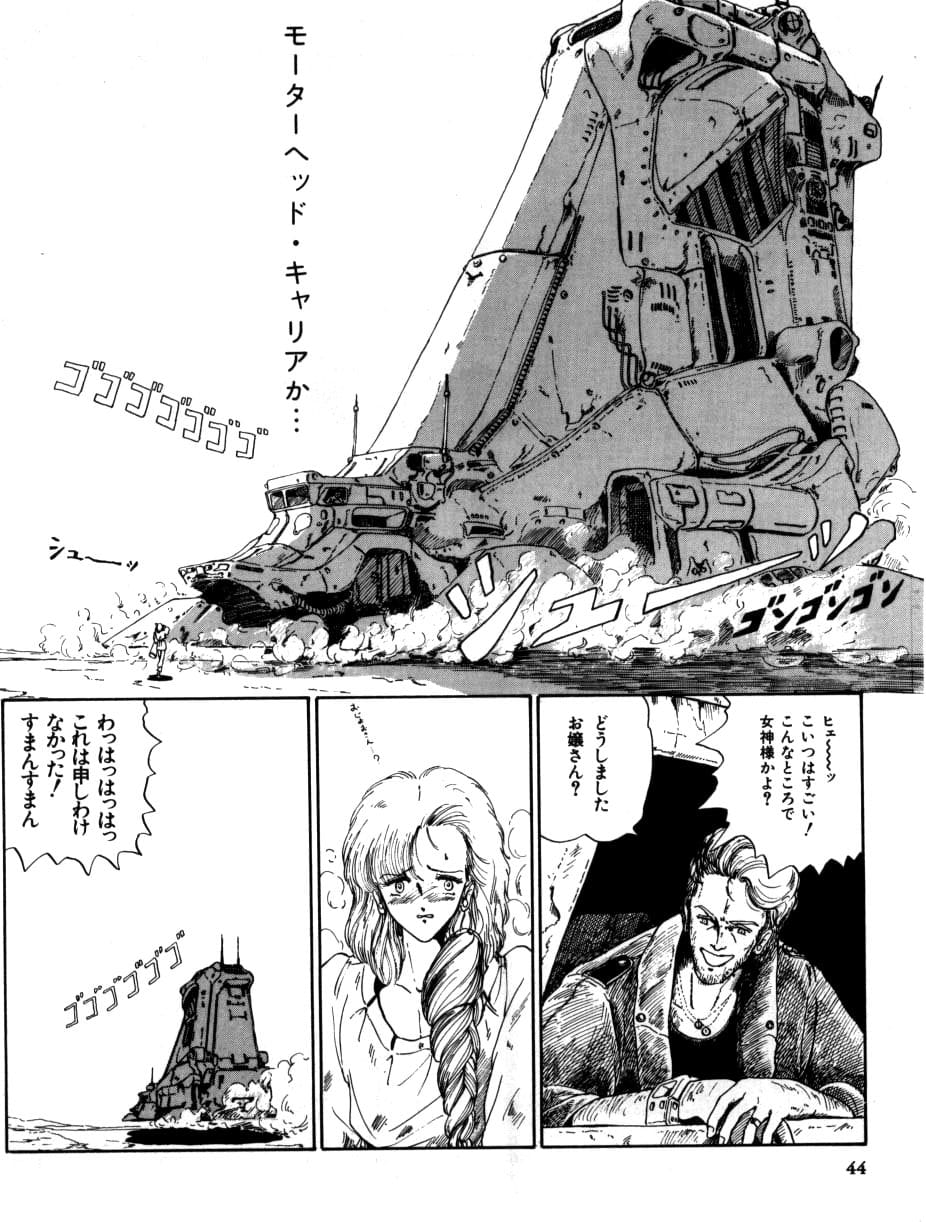

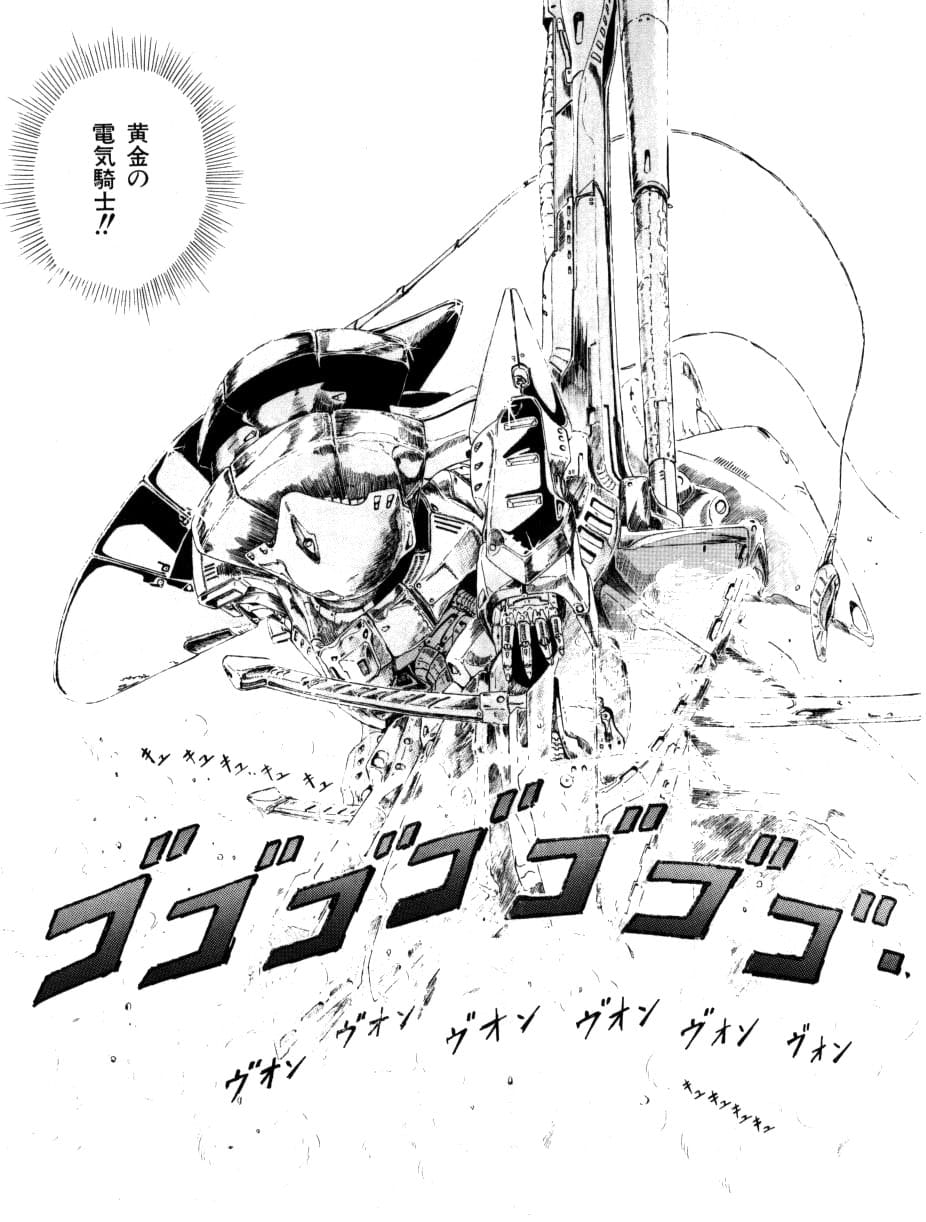

The title-earning Gothicmades do eventually show up, and they sure are giant and they sure are robot. Titanic skeletal figures resembling the bones and muscle fibers of a person transformed into glass-like metal, with piercing eyes and heads that call to mind courtroom jesters, they are arresting monstrosities, designs completely unlike anything else in the mecha landscape. They move with the sound of human screams and a mechanical thumping like electronic music. They’re strange, they’re awkward, and they’re beautiful.

Early in the film, Bellin catches Truhallon practicing with his sword in front of a group of children. The kids are enraptured by the power of this tool, and Truhallon delights in their awe. But Bellin is horrified. Here is this man coming to her home and introducing the concept of weapons — objects created to hurt — to the children. She pushes him away and makes him promise to never use it in front of them again, but it’s already too late. The kids now know of swords.

This often contradictory love and hate of the beautiful artistry behind creations of war stands at the center of Gothicmade. It’s a common consideration found in a certain generation of artist working manga and anime. You see it in Tomino and Oshii and Anno and boy howdy do you ever see it in Miyazaki. Planes and tanks and guns are such alluring objects, so elegant in so many ways. They also exist to destroy.

But whereas a movie like The Wind Rises struggles with the internal reconciling of that attraction and disgust, Gothicmade looks more outward. It suggests that witnessing a sword slicing, a gun shooting, a plane flying, or a giant robot walking — to see these marvels, these beautiful creations in action — breaks the brain in some way. There’s no going back once you know they exist. An aestheticization of violence has taken place in your brain; a justification for suffering has been born.

When violence finally occurs the film, however briefly, and Bellin sees the Truhallon in his Gothicmade killing and destroying, she can only think one thing.

“What a beautiful machine.”

But as knotted and fascinating as all of this is, the story of Bellin and Truhallon is just a tiny slice in a much bigger tale: The Five Star Stories.

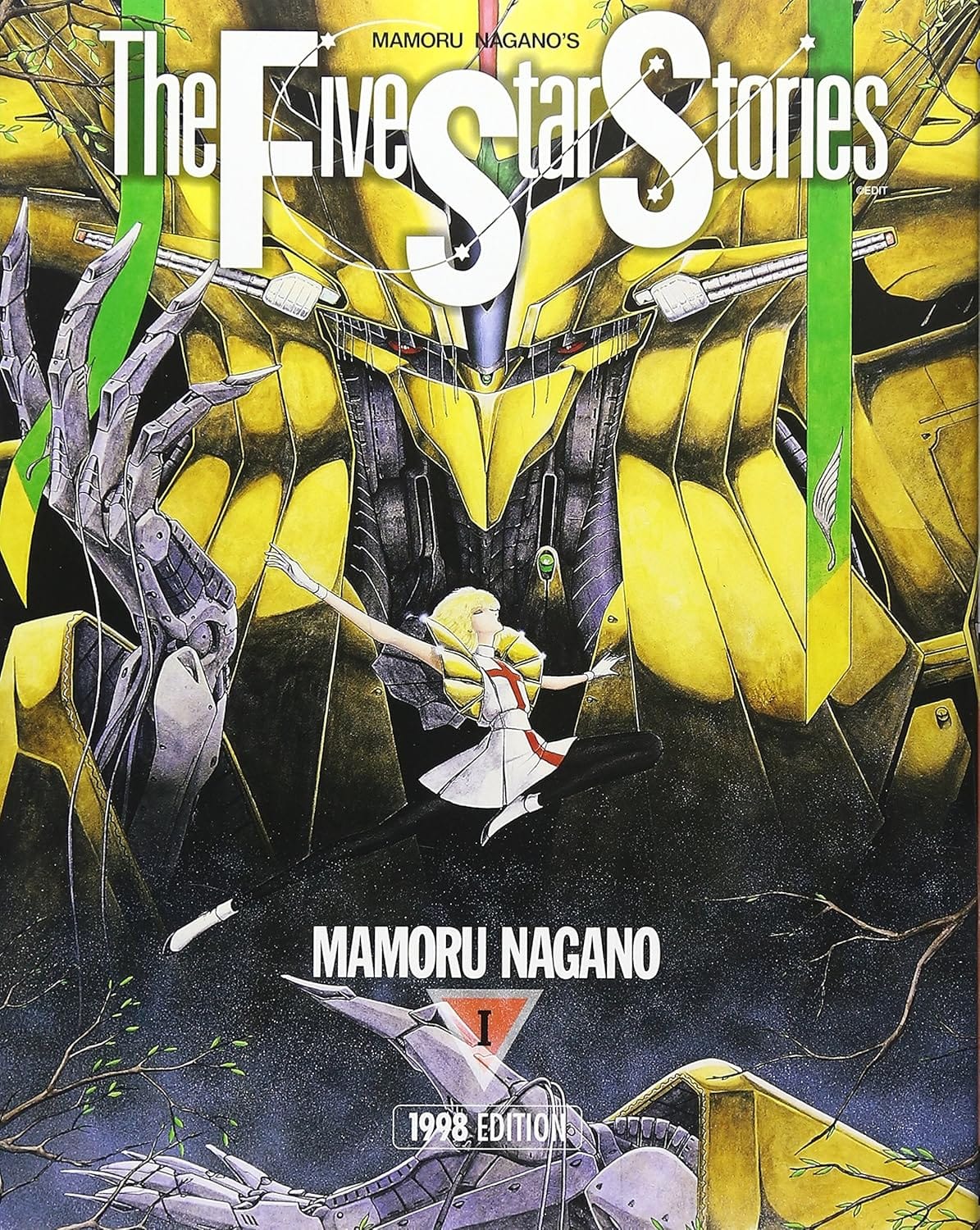

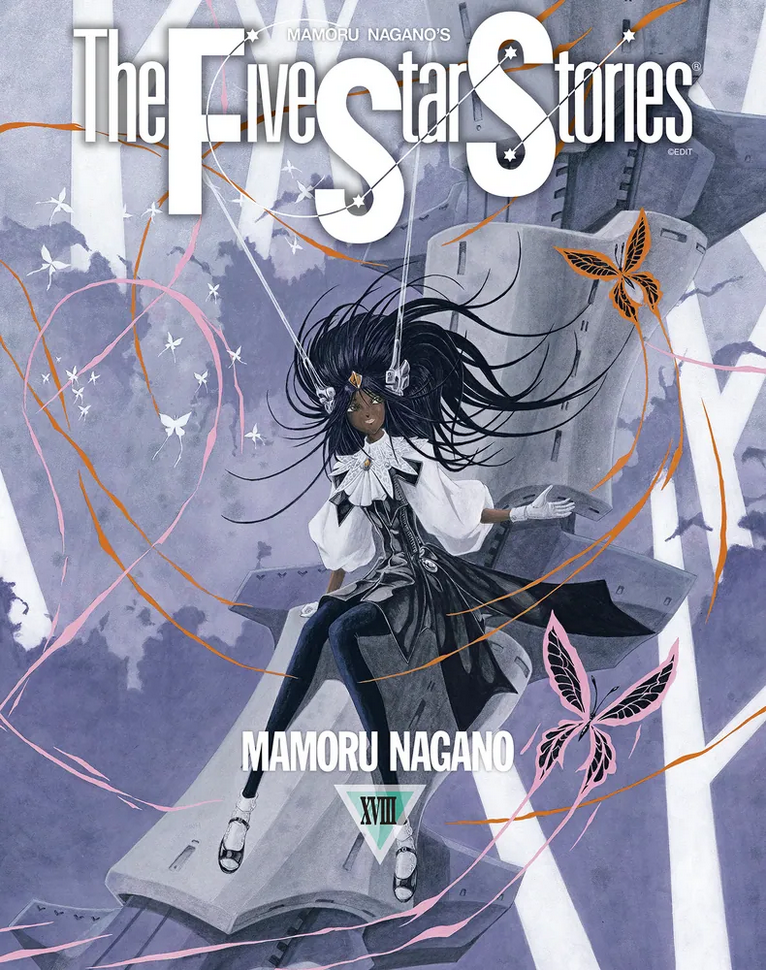

The Five Star Stories is famously A Lot. Born out of a series of lore books written by character designer (and Gothicmade director) Mamoru Nagano for the anime Heavy L-Gaim, the irregularly published manga series has become a veritable legend, a monstrous work of startling complexity and completely singular style running under Nagano’s exacting eye since 1988.

A free-wheeling and sprawling post-modern SFF fairytale epic at once extremely considered (from the start Nagano provides a detailed timeline of everything that has and will happen) and a loose playground for this single creative to dump every idea and obsession they have in their head onto the page, The Five Star Stories is the type of story you can drown in, be swept away by in the non-linear millennium spanning, perspective shifting legend of the androgynous emperor Amaterasu uniting all the stars in the Joker Solar System. It plays a collection of what Gothicmade feels like — moments in history that seem small in the grand scheme, but impossibly large to those living them — slowly placing half-forgotten pieces down to form an endless puzzle.

There are a thousand joys that come with reading The Five Star Stories, but one particular pleasure is its non-standard formatting. Manga has, for more time than it hasn’t, had its shape defined. While most are first published in larger magazines, collected volumes of manga basically exist for the tankobon, a small, easy to carry and throw in a bag size that dominates comic landscape in Japan.

The Five Star Stories is one of the rare series that defies this. With a steady, firm refusal for smaller releases and a significantly more squared page shape, to open up any given volume of the series is to unfurl a massive, cinematic ratio’d spread. Nagano is not ignorant to this either, taking full advantage of its size to highlight both scale and intimacy, dropping awe-inspiring double-page vistas and letting the average panel luxuriate in an increased horizontal space. Its size exists in perfect service to the massive scope of the story, leading to a work that feels different to read, this non-standard quality imbuing a thematically harmonious sense of importance and identity by simply existing as it is.

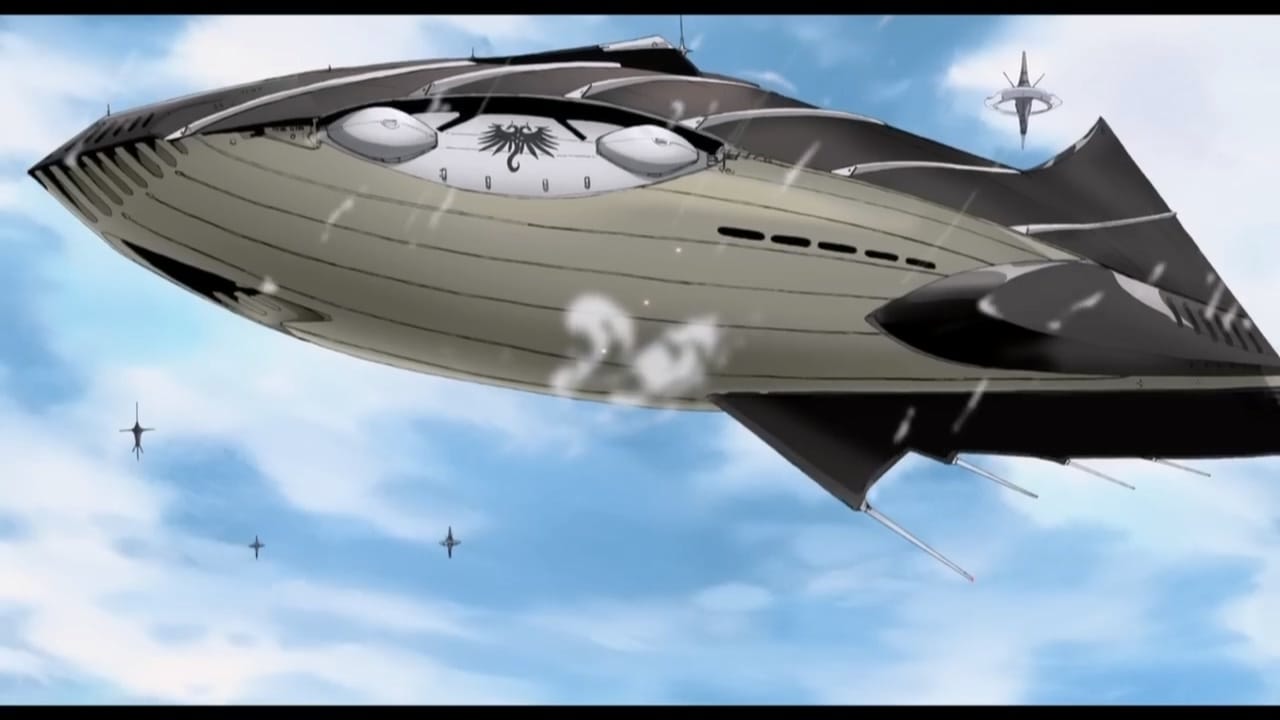

This is, ostensibly, the same reason why Gothicmade has refused any home releases. Done at a staggering 12k resolution, the shrinking of its image quality to get a 4k or blu-ray causes an unacceptable hurt to the film’s scale. At least, that’s the idea.

While Gothicmade exists firmly in line with the massive The Five Star Stories, it also isn’t just a piece of a bigger puzzle. No, Gothicmade represents a near violent shift in the trajectory of Nagano’s life work, radically updating the designs, artstyle, and terminology used going forward int he series. Now, and with no explanation, the very same robots that were once regal and weighty, the Mortarheadds, have become the skeletal, alien and ethereal Gothicmades, along with dozens of other shifts.

And you know what? It makes all the sense in the world for a series like this one, so large, so free, so packed dense with a single person’s soul, and so unending.

Similar to the iconic shounen series Hunter x Hunter, which shed the shackles of its main character with a simultaneous conclusion of their story and an obscene expansion of its world, finger pointed to the sky as if saying “this ball is going to fly forever,” you get the sense reading The Five Star Stories that Nagano has no interest in thinking about The End. After all, you know the end from moment one. The first chapter tells you what will happen; every volume provides a timeline chart all the major events that have and will occur. The end doesn’t matter. It can come at anytime, anywhere. That’s simply how everything — life, art, passion, love — works.

All that to say, Gothicmade is a fascinating movie, a strange, singular thing with a whole lot to think about and even more to take from, one built from a history and enjoying a history of its own; the kind of movie that’s a pleasure to consider once it’s over in daydreams of structure and imagery. But leaving the theater, the overwhelming thought bubbling in my brain had nothing to do with any themes or emotions or designs of spectacle presented, nor was I thinking about any solid critical consideration of the contents of the film itself.

All I could think was, “did it even matter if it was good?”

--

Back in college, I was obsessed with finding and watching Furious, a bizarre no-budget American martial arts film that feels like being shaken awake mid-dream. There’s talking pigs, an extended music video for an abrasive synth-punk band, and an absolute hallucination of a dinner scene that plays like David Lynch wandered onto set one day and took over for a bit. At the time it’d only ever been released on an extremely limited run of VHS’s that I couldn’t seem to get my hands on no matter how much I tried. Not too long after my hunt began, I found out that it’d somehow found its way onto a cheap bargain bin DVD movie collection only ever released in Australia. Perfect!

Except I couldn’t find that either.

Months of near daily searching continued, and eventually I wrapped some friends into my mounting obsession, one of whom saying they bet they could find it online and get me a copy. I refused. I refused because watching the movie like that would have felt like losing. I knew, without having seen a second of the film, that some sort of magic would die that way.

Anyway, years later, after I’d given up on ever seeing the movie, a DVD for Furious was released in the states. I bought it. I watched it. I loved it. I loved and continue to love that shoddy, broken, incomprehensible movie, and I’m as sure as I’ve ever been of anything that I wouldn’t love it half as much if its existence was easy for me.

I said earlier that it feels like most art today isn’t allowed to be lost, but that’s not entirely true. More art is being created and more stories told than at any point in our history. The nebulous “arts” have become a towering chunk of the pie chart that is our lives, a multi-faceted industry to promote the accelerated making of more, more, more. In perfect step with that, more is being lost than ever before. Small games (and large games made for multiplayer) from indie teams, movies and essays put up exclusively on YouTube, stories published on blogs and comics published on dead sites — you can find lost art everywhere you look on the internet.

There’s this little anecdote I vaguely remember but can’t for the life of me find again (which, I guess, is appropriate for today’s topic) about art curators at museums. They listen to artists tell talk about how beautiful it is for their work to die, to age to dust, to be lost to time; the existence and ending of what they creat an artistic act in itself, imbued with meaning. And the curators listen and smile and nod and it’s their job to ignore everything they say.

I’m not going to claim I’m much of an artist and I’m certainly not self-important enough to pretend that I’m any kind of real archivist, but as someone who spends too much of their time writing stories, writing criticism, and translating old forgotten media, I’m constantly in a push and pull relationship with the desire for artistic immortality and non-existence. I want so badly to both protect and share the art I love while simultaneously welcoming the inevitable vanishing of my own. All art should be remembered and saved; all art should become dust.

And here stands Gothicmade in the haze in-between those two states, both perfectly present and, in the modern conception, completely lost.

When I think of Gothicmade’s existence, I think of hunting for Furious, of dreaming about what no longer is, of finally watching that unknowable dinner scene and falling in love with it.

I think of experimental filmmaking, of Stan Brakhage and Takashi Ito and a thousand others, existing in the same halfway space. You can watch Mothlight on YouTube, but without the physical material of the film itself, have you really seen Mothlight? And if not, then what exactly is it you watched?

I think of a time I never lived in, before home recordings and film, when a movie really was trapped at the movie theater, played and then gone forever unless resurrected by the whims of the projectionist — a fate not unlike how stage theatre still largely operates — all that effort and work destined for a few hours of memories and a lifetime of looking back.

I think of writer Fernando Pessoa, and his Book of Disquiet, pontificating on the pleasures of letting dreams stay dreams, how sometimes it’s nice, better even, to let things be unexperienced, to remain as imagined objects in the mind.

When I think about Gothicmade, I think of an endless procession of knowing and unknowing in every size and shape my brain can manage: infuriating, pleasurable, sad, thrilling.

So does it matter if Gothicmade itself is good or not? Does it matter when I was allowed to dream it, allowed to long for it, allowed to one day sit down with a group of others who’d shared those dreams but also had entirely their own? Does it matter when Gothicmade is freed from the shackles of constantly being and allowed to exist “partially lost”?

Maybe that magic, that intrigue, those dreams will evaporate if Gothicmade ever finds a wider release for the home market. Maybe I’d stop thinking about it much at all then, it’s value spilling out. Or maybe it’d just change shape. Maybe it’d become something new.

I think there’s something so wonderful, so sad, and so beautiful about either fate.

(easy to say all that when I’ve actually been able to see it tho lmao)

Music of the Week | "Katyusha's Song" by Shinpei Nakayama (performed by Sumako Matsui)

A bit of a shift from the usual album posting, this song composed and performed for a stage play of Tolstoy's Resurrection has a mountain of history behind it – far too much for a single paragraph. An explosive hit signalling the start of modern Japanese popular music all the way back in 1914, and sung by the legendary actress Sumako Matsui, who's life story has enraptured people for a hundred years now, "Katyusha's Song" is also just a perfect song divorced from its importance and intrigue. Sumako sings here with such an unvarnished gentleness, like a mother singing to their child, allowing the kindness and the melancholy of the melody to wrap you up tight, each crackle and warble and pop of the record a signal of its history. One of my favorite songs.

Book of the Week | The Five Star Stories by Mamoru Nagano

Epic post-modern mecha history told like folklore; like Thousand and One Nights but each of those nights is a star in the sky you fly off to visit. Remarkably dense; this swirling interlocking tapestry of identity and gender (it’s so gender) and purpose and every other thematic interest that’s ever floated into the author’s head and filtered into romantic adventure and thrilling politicking. That alone would make it a must read, but add on an endless supply of drop dead gorgeous art depicting both the coolest giant robots and the best character designs you’ve ever seen, and The Five Star Stories becomes one of the best manga there’s ever been. I am officially obsessed.

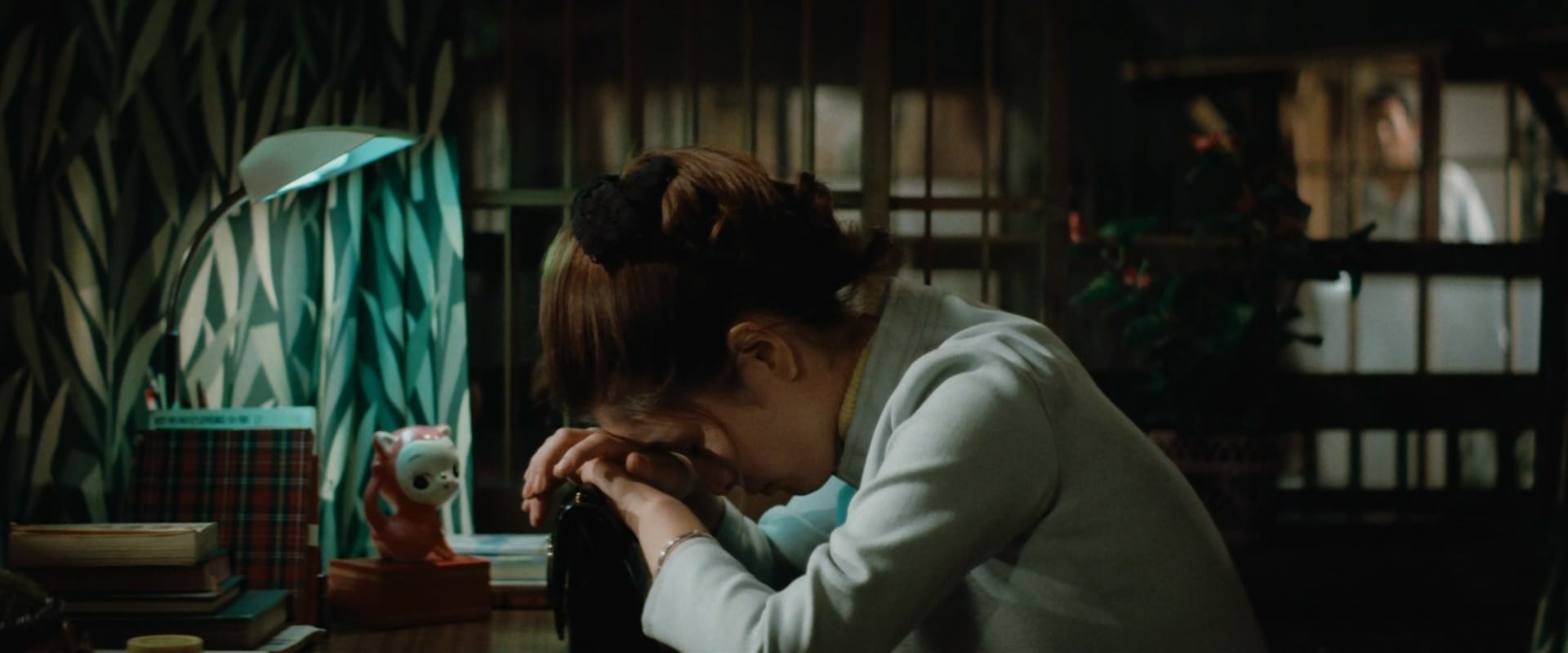

Movie of the Week | It's Tough Being a Man (dir. Yoji Yamada, 1969)

Also known as Tora-san, Our Lovable Tramp, this is beginning of the mammoth Tora-san series that lasted an astonishing fifty entries across around twenty-five years with largely the same actors and almost entirely the same writer/director. This first entry, about the ultimately well-meaning but rough around the edges Tora coming home after twenty years away from his family only to make a big mess of his sister’s romantic life, comes out the gate pretty fully formed. It’s a kind, warm movie with kind, warm humor that isn’t afraid to let the melancholy seep in or less savory character traits swell. Real food for the heart type stuff, and knowing that you’ve got forty-nine more movies to spend with this complex and lovable cast is one of the greatest feelings there is.

Have thoughts about anything covered this week? Got a recommendation you’re dying to share? Want to tell me how handsome and cool I am? Leave a comment below!

oh, and I wrote a bit about the joys of Digimon over at PC Gamer